United Kingdom Beethoven, Debussy, Hahn, Fauré and Saint-Saëns: Chloë Hanslip (violin), Danny Driver (piano), Kings Place, London, 18.4.2018. (AS)

United Kingdom Beethoven, Debussy, Hahn, Fauré and Saint-Saëns: Chloë Hanslip (violin), Danny Driver (piano), Kings Place, London, 18.4.2018. (AS)

Beethoven – Violin Sonata No.10 in G, Op.96

Debussy – Violin Sonata in G minor

Hahn – Nocturne in E flat for violin and piano

Fauré – Barcarolles – No.4 in A flat, Op.44; No.5 in F sharp minor, Op.66

Saint-Saëns – Violin Sonata No.1 in D minor, Op.75

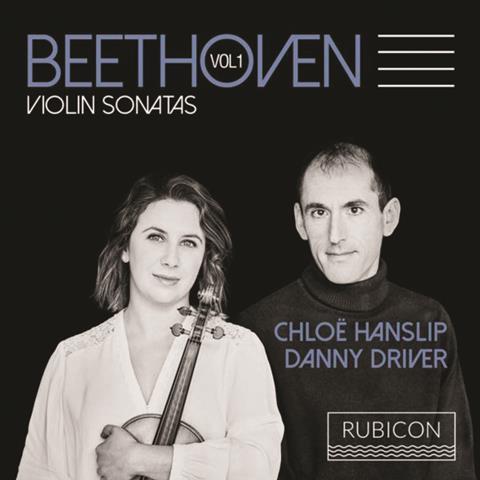

Chloë Hanslip and Danny Driver are a well-established duo and are currently recording the Beethoven violin sonatas for the Rubicon Classics label (Vol 1 review). Their second disc has recently been released.

This recital was titled ‘In Search of Lost Time’, the English translation of the title of Marcel Proust’s famous novel À la recherche du temps perdu. Proust loved the music of Beethoven and Debussy; whose music formed the first half of the programme. He was also the friend and lover of the Venezuelan-born composer and singer Reynaldo Hahn, and they both admired the music of Fauré. Proust disliked Saint-Saëns’s music, but he mentioned the D minor Violin Sonata in his letters and specifically in an unfinished novel. The fictional composer Vinteuil, who appears in À la recherche du temps perdu has been taken by some observers as having been created with Saint-Saëns in mind. Thus, the theme of the whole recital was centred on Proust’s life and times.

The first movement of Beethoven’s last sonata was given a pleasingly lyrical, poised performance, but there was a certain reticence in Hanslip’s playing: her bow strokes were limited in length and she seemed deliberately to let Driver take dominance over her playing. In the Adagio there was a certain calmness and serenity evident, but the playing was still expressive and high in concentration. Hanslip’s contribution was more positive in this movement, but in the quirky rhythms of the Scherzo it was Driver’s brilliant fingerwork that once more took the limelight. The finale, cast in variation form, was notable for the way in which each component of the movement was particularly strongly and individually characterised.

To turn at once from latish Beethoven to late Debussy needs a rapid adjustment of playing style, and in this task Hanslip and Driver succeeded triumphantly. They brilliantly caught the composer’s feverish anguish as he coped with an illness that he knew would be fatal, as well as his despair at the then uncertain fate of his beloved France in the war against Germany. I have never heard a performance that brought out the angry quality of this music so starkly and convincingly.

After the interval we heard a typically sweet flavoured piece by Hahn, delightfully melodic and rather more extended in content than his songs. This delightful composition should not rest in its present obscurity.

On his own Driver gave urbanely flowing performances of the two Fauré Barcarolles, and then he joined forces again with Hanslip in Saint-Saëns’s Violin Sonata No.1. This is another work which is unfairly neglected. It begins with a dark, turbulent Allegro agitato movement that quite belies the composer’s reputation as a fluent but facile creative spirit, and it was magnificently projected by the performers: there was no holding back by the energetic Hanslip in this work. We are then led directly into a warmly melodic, quite brief Adagio, affectionately played. A dance-like, witty Allegro moderato takes the role of third-movement scherzo, with a charmingly relaxed trio section, and this connects directly with a concluding Allegro molto finale. Here Hanslip and Driver observed the tempo indication very faithfully: this was a case of two artists playing in an excitingly virtuosic fashion, but still in perfect accord and under control. It formed a perfect climax to a most satisfying and interesting recital.

Alan Sanders