United Kingdom Chess (Music by Benny Andersson and Bjorn Ulvaeus and Lyrics by Tim Rice): Company of Chess, ENO Chorus and Orchestra / John Rigby (conductor). London Coliseum, 1.5.2018. (JPr)

United Kingdom Chess (Music by Benny Andersson and Bjorn Ulvaeus and Lyrics by Tim Rice): Company of Chess, ENO Chorus and Orchestra / John Rigby (conductor). London Coliseum, 1.5.2018. (JPr)

Production:

Director – Laurence Connor

Designer – Matthew Kinley

Original Orchestrations and Arrangements – Anders Eljas

Lighting designer – Patrick Woodroffe

Video designer – Terry Scruby

Sound designer – Mick Potter

Choreographer – Stephen Mear

Costume designer – Christina Cunningham

Cast:

Michael Ball – Anatoly Sergievsky

Phillip Browne – Molokov

Alexandra Burke – Svetlana Sergievsky

Tim Howar – Freddie Trumper

Cassidy Janson – Florence Vassy

Cedric Neal – The Arbiter

The words we hear about how ‘Each game of chess means there’s is one less variation to be played’ could equally apply it seems to the number of permutations of this 1986 musical from Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus of ABBA with lyrics by Tim Rice. I have to say here – and despite my admiration for Elaine Paige who is forever associated with Chess – I have never seen it before, so the issue of how it compares to what has been gone before is irrelevant to me.

This is the only one of the four annual musical presentations by producers Michael Linnit and Michael Grade at the London Coliseum (and in association with English National Opera) that I have seen. I have always read that they are semi-stagings but I can state here at the beginning of this review that for sheer spectacle and stagecraft there cannot be anything better currently on in the West End. Having had time to reflect I am left wondering whether I have ever seen anything better. Chess is not much worse a subject for a musical than cats or a child’s train set. Also, I have read elsewhere about how its political background is outdated – something Michael Linnit and Michael Grade commented on themselves – but so is what went on in Argentina in the 1940s and 50s, the French Revolution and the fight for American Independence in 1776 but we still want to see musicals set in these – and other – periods of history. It seems that all Chess ever needed to cement its success was for someone to devise a more dramatic book to marry all the disparate themes of competition, consumerism, greed, defection, illicit romance and political intrigue.

As it is there are several issues with the musical itself including how the characters move through it with no more motivation than pieces on a chessboard (probably not my last chess analogy). Linnit and Grade, admit in their programme introduction there could have seemed even less relevance for the show about ‘the pre-glasnost Cold War’ in 2018 compared to 1986, but little did they know ‘that relations between Russia and the West would turn so cold just ahead of our opening. So, our timing gives this musical theatre masterpiece, an unexpected, topical relevance.’ Furthermore, since they wrote this, the opportunity to experience Chess once again has gained added significance because ABBA have recently got back together to record new songs for the first time since before the musical was written.

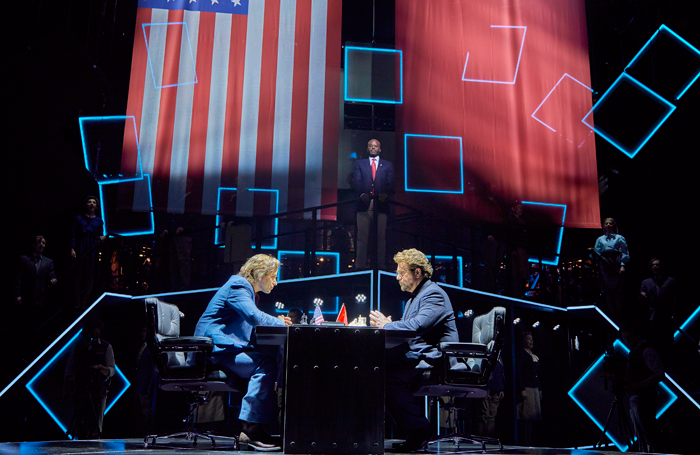

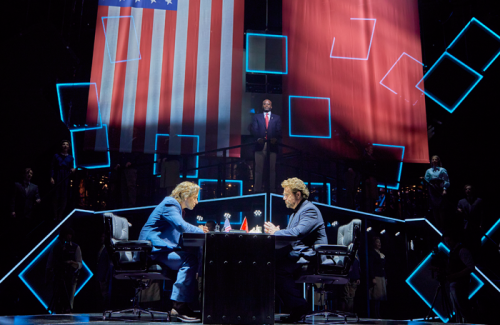

Although I doubt it is all worth the sky-high ticket prices, this revival of Chess is thrillingly staged, generally well sung but the story – such as it is – is somewhat unashamedly contrived. It begins in 1981 and takes its inspiration from the famous 1972 Bobby Fischer-Boris Spassky chess match. The players are transformed into an obnoxious American Freddie Trumper (a name to relish in 2018!) and his more stoic Russian opponent Anatoly Sergievsky. Freddie’s chess second is the Hungarian émigré Florence Vassy and she is the love interest who moves on from Freddie to Anatoly. Completing the central quartet is Anatoly’s estranged wife, Svetlana, who is used as a pawn (sorry!) by the Russian authorities in their mind games with Anatoly. The love triangle is all the more unconvincing because of all that is going on in the background; including the competition and brinkmanship between the US and Russia over the Space Race and Arms Race, as well as, the hullaballoo and tedious po-faced pageantry of the international chess circuit.

Matt Kinley’s set must have cost a fortune and uses the iconic fractured chessboard imagery for the musical to provide an imaginative backdrop of LED screens to show – thanks to Terry Scruby’s video designs – an airplane landing at Bolzano airport (that has to be seen to be believed), the Italian mountain resort of Merano, the less salubrious side of Bangkok; or allows us to see montages about the Cold War, other animations or – in the manner of stadium or arena concerts – huge sophisticatedly shot closeups of those on stage that draws you into their performances. Stephen Mear’s high-octane choreography keeps everyone – almost literally – on their toes. There are some anachronisms with Merano – holding on to its German roots – being all lederhosen and drindls and all we needed were some Nazis and it could have been a scene from The Producers’ ‘Springtime for Hitler’. The well-known ‘One Night in Bangkok’ gets a slightly unsavoury parody of Thai nightlife – complete with ‘ladyboys’ – that is familiar from Miss Saigon and four high-kicking British Embassy officials hint at the Pythons’ ‘Ministry of Silly Walks’.

And like the game, Chess makes its demands of all concerned including the band – or, as here, English National Opera’s Orchestra – because the score reflects almost as many musical genres as there are chess pieces (sorry again). It is basically an opera, but with jazz, rock, pop, rap, and much else in Anders Eljas’s orchestrations and arrangements. There is also a particularly haunting melody for the almost interminable Trumper-Sergievsky chess confrontation that Ennio Morricone would be proud of. The orchestra – conducted by John Rigby and hiding in plain sight at the rear of the stage – dealt well with this cornucopia and were excellent throughout. However, their amplified sound was often too loud and as most of the story unfolds in song, it is crucial all the lyrics can be heard clearly, which is not often the case. The combined ensemble and ENO Chorus sang lustily and loudly and were well drilled to enthusiastically handle the complicated dance moves that Stephen Mear choreographed.

Tim Howar as Freddie Trumper manages the swagger, braggadocio, maliciousness, anger and belittling of the people who support him, with great conviction. Just when you are revelling in your dislike of this character, he sings the heartrending ‘Pity the Child’. Howar was at his best here, whereas before he had just often shouted rather than sing properly. Despite of his great experience of musical theatre this is probably because of his background as co-frontman of rock-band Mike + The Mechanics.

As his opponent Anatoly Sergievsky, Michael Ball gave a West End masterclass. He can equally croon a torch song, ‘You and I’ or raise the roof with ’Anthem’ which earned him a standing ovation at the end of Act I. He delivers everything with great confidence and power and it is not his fault that we really do not get to know or empathise with Anatoly who flipflops between his wife and lover. Thankfully he does not attempt a noticeable Russian accent.

Both these characters manoeuvre around the queen in this chess game of life, Florence Vassy, and Cassidy Janson takes the role created by Elaine Paige. She shoulders most of any emotional tension there is in what we are seeing and bravely tackles all those varied musical genres thrown at her. Like Howar she, too, seemed to forget she was wearing a microphone and often pushed her voice too much and it became shrill. She was best in the more introspective moments of ‘Heaven Help My Heart’, ‘You And I’ and the gloriously poignant duet ‘I Know Him So Well’ with Alexandra Burke’s Svetlana when they express their different feelings about Anatoly. At no point did it seems Janson wanted to make any of these songs ‘her own’ and sounded as if she was paying homage in all she did to Elaine Paige.

As Anatoly’s Russian wife, Alexandra Burke did the best she could in a disappointingly underwritten role. It is late in Act I before she introduces herself with ‘Someone Else’s Story’ and her soulful voice and understated performance deserved ‘He is a Man, he is a Child’ – from the Swedish version of Chess – at the start of Act II. Also making the most of what little Chess gives them to do were Cedric Neal singing with authority and gravitas as the Arbiter, whilst the resonant Phillip Browne is someone I would definitely like to hear again in a more substantial role and he impressed as the conniving and uncaring Molokov.

Jim Pritchard

For more about Chess at the London Coliseum click here.