United States Britten, A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Soloists, Orchestra and Chorus of Opera Philadelphia / Corrado Rovaris (conductor), Academy of Music, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 10.2.2019. (BJ)

United States Britten, A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Soloists, Orchestra and Chorus of Opera Philadelphia / Corrado Rovaris (conductor), Academy of Music, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 10.2.2019. (BJ)

Production:

Director & Lighting designer – Robert Carsen

Revival Director – Emmanuelle Bastet

Choreographer – Matthew Bourne (revived by Shelby Williams)

Set & Costume designer – Michael Levine

Lighting design – Peter Van Praet (revived by Adrian Plaut)

Chorus master – Elizabeth Braden

Children’s Chorus master–Jeffrey Smith

Cast:

Oberon – Tim Mead

Tytania – Anna Christy

Puck – Miltos Yerolemou

Helena – Georgia Jarman

Hermia – Siena Licht Miller

Lysander – Brenton Ryan

Demetrius – Johnathan McCullough

Theseus – Evan Hughes

Hippolyta – Allyson McHardy

Bottom – Matthew Rose

Flute – Miles Mykkanen

Quince – Brent Michael Smith

Snug – Patrick Guetti

Snout – George Somerville

Cobweb – Jack Cellucci

Peaseblossom – Timothy O’Connor

Mustardseed – Evan Schaffer

Moth – Payton Owens

It would be foolhardy to accuse anything the Bard of Avon wrote more than four hundred years ago of lacking contemporary relevance for us now in the 21st century. To the amusement of the audience at this post-U.S.-government-shutdown performance of Britten’s great Shakespearian opera, the play-within-a-play near the end included the prominent impersonation of that contentious item, a Wall. Hilariously realized in this production, it was well worth a spot of delighted laughter and applause, and it was just one among a goodly number of jokes in the work and its realization, several of them created by Miltos Yerolemou’s suitably seditious Puck.

Casting the operatic A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a tall order to start with. You need a team of youthful singer-dancers for Shakespeare’s fairies, and two adult singers — one of them a countertenor — to play their king and queen; another dozen grown-ups to represent both the polished Athenian nobles of the plot and the ‘rude mechanicals’ who so gauchely yet endearingly try to entertain them; and a fleet-footed actor to play Puck, the mischievous imp whose carelessness sets the story on its accident-prone course.

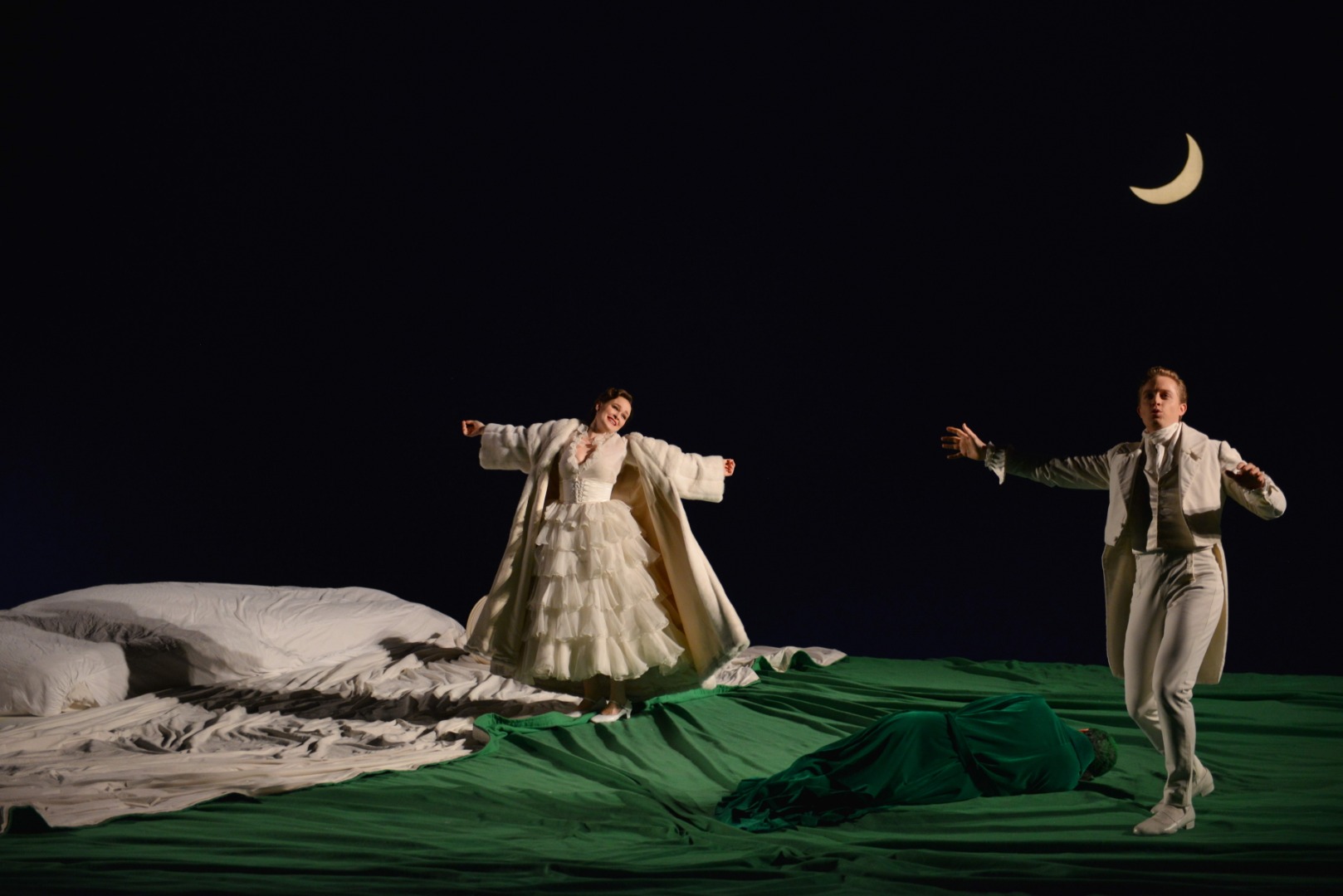

Originally staged by Festival d’Aix-en–Provence and Opéra National de Lyon, the first United States presentation of Robert Carsen’s widely traveled and equally widely celebrated quarter-century-old production, which I was myself encountering for the first time, delivered generously on all these requisites. Restaged here by Carsen’s assistant Emmanuelle Bastet, it profited from the contributions of a uniformly excellent array of solo voices, notably featuring those of countertenor Tim Mead and soprano Anna Christy in the leading fairy roles. Corrado Rovaris led a well-paced and lucid account of the score; I cannot remember ever hearing the words of a text so clearly in any operatic performance, and Britten’s skillful orchestration must share the credit for this with the maestro’s impeccably balanced textures. Orchestrally, chorally, and choreographically, too, all was in order.

The visual aspect of the production was certainly effective, but to my mind rather less comprehensively so. A colleague of mine already acquainted with it had described it to me as ‘magical’, and by Carsen’s own account, his intention was ‘to create as magical a production as we could, without [my italics] resorting to creating a so-called real fake forest on stage, with real fake trees and real fake foliage.’ In common with the approaches of many contemporary directors, his desire to make his forest metaphorical rather than physically realistic is understandable, but I would have been happier if he had explained why, which is what I always want to know about such directorial decisions. And in the present case I cannot refrain from comparing the often amusing and sufficiently clean but somewhat prosaic look of Michael Levine’s sets with the effect of the ravishing stage design and lighting that John Bury brought to his 1981 Glyndebourne production of the work. Now that was truly magical, and the way we saw the trees gradually materialize out of the mist keeps its place in my mind, nearly forty years later, as one of the three or four most vivid visual memories I cherish from more than half a century of opera-going.

Ah, well — I suppose we can’t expect every visit to the theater to reward us with an experience of pure, flawless magic. What this production gave us, without quite scaling the ultimate heights of inspiration, was a thoughtful and arresting realization of Shakespeare’s and Britten’s enchanting and powerfully humanistic masterpiece.

Bernard Jacobson

What a dreadful and narrow sighted review. This was one of the most joyous and well given performances I have been to in my life and absolutely the best thing I have seen Opera Philadelphia do, and this curmudgeon drivels negatively on..I am so grateful to have seen this and could have happily gone several times more. It was magnificent and great theatre, With a brilliant and energised cast. I would say there were problems in the pit, this piece is beyond this limited orchestra and conductor, but your reviewer couldn’t get past the fact that he wasn’t at Glyndebourne..please, reviews like this have no place..

This was not my review of course but did you read the same one as I have?? This comment does not reflect in any way the generally positive nature of this review.

I did indeed read the review, in which your writer mostly goes in about how this production isn’t quite as magical as the one at Glyndebourne

He doesn’t talk really about many individual brilliant performances from every member of the cast, his only comment being on Tytania and Oberon who weren’t the only excellent performances by a long way. How he couldn’t mention the Puck or Bottom who both outshine those other two in energy and brilliance for example..it’s not a good review at all, it’s curmudgeony and not at all indicative of what i and many others saw and heard and laughed at..

My thanks to Jim Pritchard for so gallantly riding to my rescue. I would ask Mr. Rosen to take another look and see whether he really thinks three paragraphs of sustained enthusiasm, followed by one paragraph mildly critical of one aspect of the production, and then a conclusion rating the production as thoughtful and arresting can really be characterized as narrow sighted and curmudgeonly.

I don’t think any fair-minded reader will blame me for being less than overwhelmed by a comment about my mostly going on about a Glyndebourne production that is mentioned in just five of my review’s 51 lines, and then to ask and illustrate a very specific question in response to Robert Carsen’s deliberate avoidance of the literal representation of trees.

Puck is indeed mentioned right up in the first paragraph of the review. But Mr. Rosen is right in saying I should have mentioned Matthew Rose’s magnificent singing and acting as Bottom – I had intended to do so and then forgot.