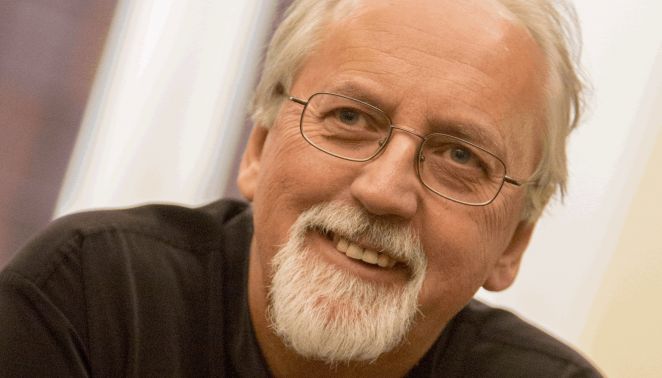

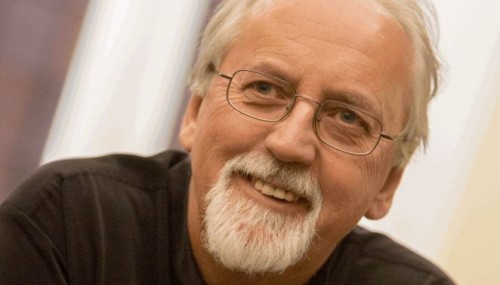

United Kingdom Monteverdi: Ex Cathedra Consort & Baroque Ensemble, His Majestys Sagbutts & Cornetts / Jeffrey Skidmore (conductor). St David’s Hall, Cardiff, 4.4.2019. (PCG)

United Kingdom Monteverdi: Ex Cathedra Consort & Baroque Ensemble, His Majestys Sagbutts & Cornetts / Jeffrey Skidmore (conductor). St David’s Hall, Cardiff, 4.4.2019. (PCG)

Monteverdi – Vespers

As Jeffrey Skidmore quite pertinently observed in his programme notes, it would seem that every individual performance of the Monteverdi Vespers comes with its own exclusive edition which can differ to a surprising degree from any other. This was most certainly the case here. The contrast between this concert in St David’s Hall and the performance of the same score given in Llandaff Cathedral less than six months ago (review click here) was quite remarkable when one considers that both were based on exactly the same printed material as published by Monteverdi in 1610. Both editions concurred in the individual movements included (with the omission of the unaccompanied mass and the smaller-scale Magnificat) and the order in which these movements were performed; but here Skidmore inserted relevant plainchants between those movements, employing them imaginatively to allow for a redistribution of his singers about the platform to provide contrasting antiphonal bodies where required. This also avoided the need for any retuning (or cues for choral pitch) between movements, except right at the end where the organ needed to be recalibrated for the final Magnificat – which meant that the single interval came at an unconventionally late point in the proceedings.

The performance here, although it featured some of the same players in the shape of His Majestys Sagbutts & Cornetts whom we had also heard in Llandaff last December, also provided a major contrast in terms of scale. Instead of the massed choral forces of the Llandaff Choral Society – which meant in turn that editorial decisions were also required as to which passages should be assigned to soloists as opposed to chorus – we had a mere ten singers, who for the greater part of the evening were allocated with one voice to a part. This avoided any necessity for making distinctions between sections, but at the same time it did mean that the grander sections of the score could have possessed more – well, grandeur. It is of course true that Monteverdi published his score before he took up his post in charge of the music at St Mark’s in Venice, but I cannot believe that he would have not made use of larger choral forces in that larger location when he gave performances there. His instruction over the final section of the Magnificat ‘tutti li stromenti & voci, & va cantano & sonata forte’ can surely leave little doubt of his intentions in this regard. Perhaps it was best to regard the performance here as designed for one of the Italian ducal or princely chapels, where smaller-scale performances would have been given during Monteverdi’s lifetime. (It seems, however, that even when he was in Mantua the composer had access on occasion to a fairly substantial courtly musical establishment.) Once the ear adjusted to the smaller scale of the performance, balances were ideally judged even in the large spaces of St David’s Hall; the absence of the ecclesiastical acoustic was nevertheless to be felt in places.

The smaller-scale movements which make up the greater proportion of the score were of course entirely unaffected by these considerations. The madrigal-like textures of such motets as the Pulchra es or Duo seraphim came across with a crystal clarity, and there were many other points where the tricky and often subtle changes in rhythm had a sense of propulsion which an ecclesiastical acoustic would have smudged or blurred. The echo effects in Duo seraphim were sublimely beautiful, but unfortunately that was not the case in the Gloria Patri of the final Magnificat; the second tenor (who only had time to position himself marginally off stage) came across to where I was seated as louder than the first tenor placed in the centre of the stage which he was supposedly echoing. This was fortunately only a momentary misjudgement in a performance where the actual positioning of the singers and players had obviously been carefully considered. The string players, for example, were asked to stand during their soloistic passages, although this did not solve the balance problems in the sonata Sancta Maria ora pro nobis where they were effectively overpowered by the cornetts. The lack of cathedral resonance robbed their tone of richness and smothered their superlative articulation.

In his programme note Jeffrey Skidmore quoted some ‘deliciously naughty words’ written in 1967 by Denis Arnold about the Monteverdi Vespers: ‘To write about it is to alienate some of one’s best friends. Even to avoid joining in the controversy is to find oneself accused of (i) cowardice, or (ii) snobbishness, or (iii) sitting on the fence, or (iv) all three.’ At the risk of falling into the final category, I must observe that while I would not always wish to hear the Vespers performed on such a small and intimate scale, I found this rendition illuminating and rewarding at many junctures.

The programme booklet, apart from the extensive essay by Jeffrey Skidmore, commendably provided complete Latin texts and translations, even including the plainchant antiphons. Skidmore’s essay was not only informative about editions and transpositions of the music, but admirably frank about the aesthetic spirit of the work confessing freely that ‘the debate goes on!’ He quoted an anonymous 1953 review which described a performance under Anthony Lewis as ‘vivacious, exciting, teeming with conviction, and above all constantly dancing’ and hoped that the same might ‘be thought of our performance’. I am extremely happy to oblige.

Paul Corfield Godfrey