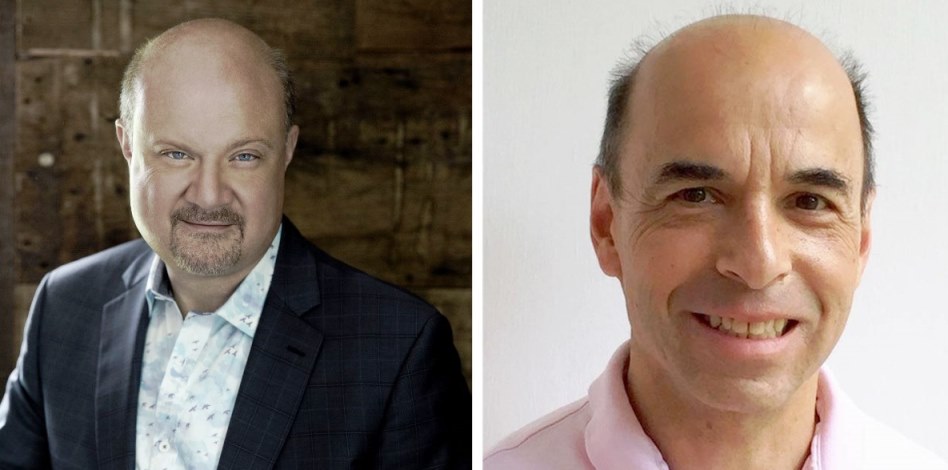

United Kingdom Schubert: Randall Scarlata (baritone), Robert Taub (piano). University of Plymouth Sherwell Centre, Plymouth, 12.10.2019. (PRB)

United Kingdom Schubert: Randall Scarlata (baritone), Robert Taub (piano). University of Plymouth Sherwell Centre, Plymouth, 12.10.2019. (PRB)

Schubert – Winterreise, Op.89

This is the third event in the Musica Viva Concert Series at the University of Plymouth, which aims to bring top-quality international artists back to the city. The inaugural concert in March presented the London Mozart Players (review click here). Arts Institute Director of Music Robert Taub joined them in a superb performance of Mozart’s D minor Piano Concerto. This was followed a few months later with another equally successful recital. The Dante String Quartet was joined once more by Taub in a scintillating reading of Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet (review click here). The resulting packed houses on both occasions were a delight to report on, though admittedly not overly surprising because of the popularity of the artists, and the attractive nature of the repertoire on offer.

When I first heard that the projected third event in this excellent new initiative would be a solo vocal recital, it took me back to the sixteen or so years of the former Plymouth Chamber Music Trust Series, which brought to the city virtually all the leading chamber-music artists, both vocal and instrumental. It was always the case, though, that vocal music – whether solo or ensemble – drew a smaller audience than purely instrumental music, and consequently had far fewer slots in the calendar each year.

Furthermore, the recital was to be given by Taub’s friend and former professional colleague from back in the States, Randall Scarlata. Scarlata was not a name I had encountered before, but checking him out later online showed he is, as they say, ‘very big across the Pond’. There are numerous accolades and glowing reviews from some of the most well-respected sources and critics in the United States.

Following the format of the previous two Music Viva events, the concert was prefaced by a short talk about Winterreise. Both performers gave fascinating insights into what the work meant for them individually, and how they planned to present this collectively. Always mindful of the greater need for the vocalist – rather than the pianist – to prepare for the imminent performance, Scarlata wisely left the stage to prepare the voice, leaving Taub to answer some fascinating questions posed by members of the audience. This kind of pre-concert discussion is so vital, not because it can elaborate on some of what was already written in Taub’s highly-informative programme notes – with a couple of musical quotations to boot – but because it shows the real chemistry and empathy between the performers in an informal, non-performance setting. And, despite my initial reservations about vocal chamber music, even if the hall was not quite jam-packed, the recital was certainly well supported.

The use of the score is perfectly acceptable in oratorio work, but in solo work you seek to hide it, or try to deny its presence, because otherwise it represents a physical barrier between singer and audience. To memorise Schubert’s twenty-four Lieder – none of which is in your native tongue – is a real feat in itself. Simply in terms of Scarlata’s German, I have it on the very best authority from a native German speaker, that they were able to understand every word of the text, and that the pronunciation showed no sign of Scarlata’s early Pennsylvanian upbringing. To sing Winterreise from memory is so very important in conveying the idea that this is not a mere collection of songs, but that they are all inextricably linked to a central theme, and even with some shared thematic material. This is the rationale of the Song Cycle, or Liederkreis: individually complete songs, designed to be performed in a sequence as a unit.

Then there is, of course, another problem. For many years, operas have enjoyed using sub/surtitles for real-time translation. Concert halls tend to rely on a printed translation for the audience to follow, say, the German on the right of the page, and English on the left. They will all tend to turn the page at the same time, so here, for example, this involved eight sides of A4 back to back, stapled together. That hardly caused any significant hiatus during the recital. The real and most unfortunate problem here was that looking down to the translation meant missing the second essential aspect of the performance: Scarlata’s wonderfully absorbing body language, not just during each song, but during the piano introduction and closing symphony, and equally important between the songs. I was so glad that I never once looked at the text or its translation. I can only get by in German, so I did not understand every single word, but I did not need to. Schubert’s wonderful music, Scarlata’s supreme stage presence and Taub’s highly sympathetic accompaniment simply said all I needed to know at any point in the performance. Even now – and it was over in a blink – I recall a sublime moment at the close of a song: Scarlata, having finished his contribution, cheekily looked upward with a kind of wink, which just seemed so apt

Scarlata’s voice and delivery were all that I had hoped for. There is real power at the top as he almost started venturing into tenor country, yet his is equally a voice of real substance at the bass end. Pitch, intonation and ensemble were virtually flawless throughout all the Lieder sung without a break. Scarlata’s voice production and control of dynamics were exemplary, like a large engine with more to offer if needed, rather than a smaller one running almost flat out.

The performers’ decision to leave the lid fully open on the Steinway mid-sized grand was a wise one. In this work, the piano part and the voice are inextricably linked, and if one actually dominates the other, the effect of Schubert’s masterly setting and balance can so easily be compromised.

Taub is a superb solo technician at the keyboard, but he is also a great listener and accompanist. When the piano needed to dominate the texture, it certainly did, but at no time did it overpower the voice, even at the most hushed vocal dynamic. That great bond of friendship we witnessed at the start of the evening when Messrs Scarlata and Taub talked informally to the audience, was still there during the rest of the evening, too, but, under the guise of Herr Schubert – and Herr Müller, whose twenty-four poems inspired the composer to write this most iconic of works for the voice.

And, for at least a couple of hours or so, this most memorable of evenings must surely have dispelled all thoughts of Brexit, as we accompanied this traveller on his winter journey, with ne’er a border in sight – hard or soft.

Philip R Buttall