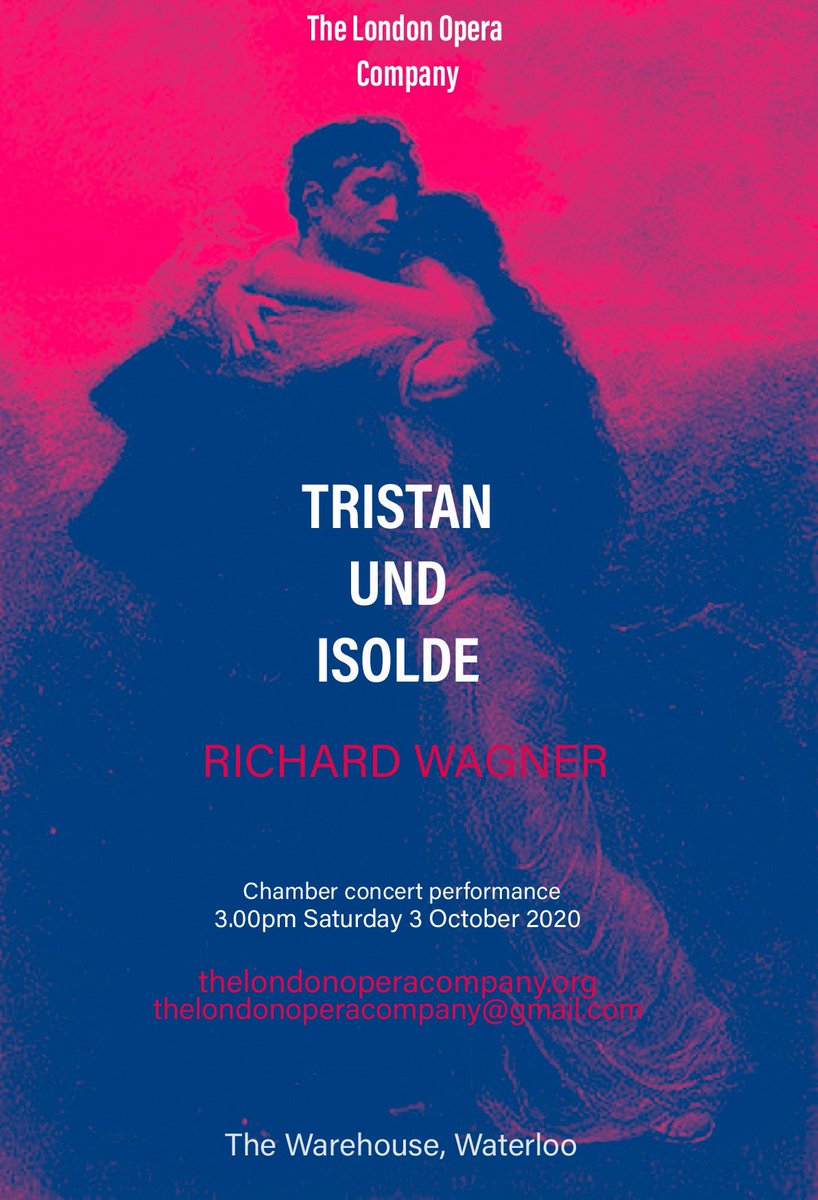

United Kingdom The London Opera Company – Wagner, Tristan und Isolde: Soloists, James Widden (violin), Alison Holford (cello), Jonathan Musgrave (piano) / Michael Thrift (conductor). The Warehouse, Waterloo, London, 3.10.2020. (MB)

United Kingdom The London Opera Company – Wagner, Tristan und Isolde: Soloists, James Widden (violin), Alison Holford (cello), Jonathan Musgrave (piano) / Michael Thrift (conductor). The Warehouse, Waterloo, London, 3.10.2020. (MB)

Cast:

Tristan – Brian Smith Walters

Isolde – Cara McHardy

Brangäne – Harriet Williams

Kurwenal – Louis Hurst

King Marke – Richard Wiegold

Young Sailor – Ben Thapa

Melot – Jonathan Cooke

Shepherd, Steersman – Bo Wang

Almost a year to the day (5 October 2019) since I had last seen Tristan und Isolde and considerably sooner, given the world’s catastrophic state, than I had anticipated, Wagner and Tristan returned to my life and to the lives of the performers of The London Opera Company, here giving its inaugural performance. For any company to open proceedings with Tristan is a declaration of intent, not least in London, so starved of Wagner compared to any city of its stature. Yet, this group of musicians determined not so much to keep the flame burning as, in contradistinction to its eponymous lovers, emphatically to ignite it — ‘Das Licht! Das Licht! — showed a heroism as impressive and as moving in achievement as in conception. It is their hope that this will ‘inspire further chamber performances’; it should be ours too.

So much Wagner is in any case chamber music, a fact readily acknowledged by all Wagner conductors worth their salt. It is simply that, as with Liszt, the chamber music is usually part of a grander scheme rather than the basis of a work in itself. There are certainly gains to be had in a small performing space in which no singer feels the need to force his or her voice and facial expressions can readily be observed, in which one can be drawn into the noumenal realm of Night and shun the phenomenal realm of Day. Michael Thrift, as he had with a slightly larger-scale Parsifal whose first act I heard four years ago in Chiswick, conducted a flexible, directed account of the score that may well, at some level, have had one long to hear him communicate such understanding in front of an orchestra — from time to time, how could it not? — yet equally seized upon the virtues of a chamber performance and had one appreciate them in themselves more than one might ever have imagined. When timbre and texture are transformed in this way, one finds oneself both listening to what is different and also switching the focus of one’s attention elsewhere. Jonathan Musgrave’s battle to convey Wagner’s orchestral writing on the piano, ably assisted by James Widden on violin and Alison Holford on cello, made for absorbing listening. Even Liszt would have had his work cut out here; indeed, it was the Lisztian delicacy to the more intimate moments and passages, doubtless informed by contrast with more public, shattering surges of the Wagner-Schopenhauer melos-in-Will, which lingered longest in the emotional memory.

Brian Smith Walters, Parsifal in that earlier performance, showed himself every inch a Heldentenor here as Tristan. It is an impossible role and, goodness knows, I have heard some performances one could only have wished were impossible; this was certainly not one of them. Vividly communicative in verbal as well as musical terms — the small space doubtless helped, but it was not only that — Smith Walters paced his performance wisely, affording as keen a developmental edge as anyone might wish for, culminating in the agonies of Kareol and longed-for release. His was a profoundly human journey, for all the metaphysics surrounding it. So too was that of Cara McHardy as Isolde, whose Isolde likewise reacted to dramatic circumstance, her path to ecstatic transfiguration uncertain in the here-and-now, commendably clear in retrospect.

It was fascinating to hear from her and Harriet Williams as Brangäne during the first act the roots of Wagner’s vocal writing in earlier opera. Shorn of rich orchestral tapestry, the score, or better one’s aural perspective upon it, yielded other secrets: words and their meaning, so often overlooked in the musicodramatic maelstrom that is Tristan; chippings from a grander bel canto than had ever empirically been; and yes, paths to a Schoenbergian future to voice-and-ensemble too. Williams’s performance, wise and compassionate, with deeply affecting vocal colour — chalumeau with words in one register, at one point — had one long for more. Indeed, not only was there no weak link in the cast; the strength of ensemble and interaction made it considerably more than the sum of its parts. Louis Hurst’s honest Kurwenal, finely etched accounts of the Young Sailor and Melot from Ben Thapa and Jonathan Cooke, and Richard Wiegold’s sonorous King Marke, the latter redolent at times of notable Nordic predecessors in particular, all added greatly to that overall sum. It was, however, perhaps the sincerely communicative qualities Bo Wang’s Shepherd and Steersman that made the greatest impression on me: nothing taken for granted, without the slightest hint of fuss. To single out further would doubtless be to miss the point. Many thanks to all concerned for so accomplished and so moving a company debut.

Mark Berry