Italy Mascagni, Leoncavallo, Cavalleria rusticana / Pagliacci: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Comunale di Bologna / Frédéric Chaslin (conductor). Originally livestreamed (9.2.2020) on OperaStreaming by Edunova. This was reviewed on YouTube and it is available via SoundCloud. (CC)

Italy Mascagni, Leoncavallo, Cavalleria rusticana / Pagliacci: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Comunale di Bologna / Frédéric Chaslin (conductor). Originally livestreamed (9.2.2020) on OperaStreaming by Edunova. This was reviewed on YouTube and it is available via SoundCloud. (CC)

Cavalleria rusticana

Production:

Director – Emma Dante

Set – Carmine Maringola

Costumes – Vanessa Sannino

Lighting – Cristian Zucaro

Choreography – Manuela Lo Sicco

Cast:

Santuzza – Sonia Ganassi

Turiddu – Angelo Villari

Lucia – Claudia Marchi

Alfio – Stefano Meo

Lola – Alessia Nadin

Pagliacci

Production:

Director – Serena Sinigaglia

Set – Maria Spazzi

Costumes – Carla Teti

Lighting – Claudio De Pace

Assistant Director – Andrea D’Amico

Set Assistant – Marianna Cavallotti

Cast:

Nedda/Colombina – Carmen Solis

Canio/Pagliaccio – Stefano La Colla

Tonio/Taddeo – Stefano Meo

Beppe/Arlecchino – Paolo Antognetti

Silvio – Vincenzo Nizzardo

This Cav & Pag is a co-production by Teatro Comunale, Grand-Théâtre de Genève, with Fondazione I Teatri di Reggio Emilia. As in the case of Massenet Werther (review) and Purcell Dido (review), both from Modena, and a Handel Aci, Galatea e Polifemo from Piacenza (review), dramatic standards are of the highest; and in this case, vocal standards match. With the absence of Opera Holland Park this year due to the ongoing pandemic, there are many in the UK, surely, who need a shot of verismo: here it is.

Both productions here are intelligent; both create atmospheres that fully match the glowering passion of the operas’ plots. In the Mascagni, we have a traditional orchestra-only Prelude (with no unnecessary director-led additions onstage). The stage itself for Turiddu’s serenade to Lola is dark and almost empty, just one structure which shown a door with a balcony above it. Angelo Villari is nicely distanced off-stage, his voice clearly strong and virile. Lola (Alessia Nadin) listens, at the balcony above the door. fanning herself (fans are to play something of a part in this production, not least in the female choruses in the first scene proper, ‘Gli aranci…’ and so on – where they look like butterflies flitting between the flowers of the text).

It is only then the symbolism truly begins; a Christ-figure weighed down by a cross that falls on him, whipped by a Super-Mario manic centurion (an image repeated during the Intermezzo). Females enter in mourning, dressed in clothes and colours redolent of Raphael’s Madonna del Granduca and the suchlike. Throughout all of this, the orchestra excels under Frédéric Chaslin; the way it positively explodes after the Serenade is superb (later, Chaslin is to shape the famous Intermezzo superbly).

Bells ring over an empty, dark stage; we see acrobats and two girls in an argument (presumably over a man). Mamma Luci, here Claudia Marchi, is a fabulous complement to Santuzza; there is a great meeting of voices in their scenes, both strong, but Santuzza definably younger; and we believe Santuzza when she says she cannot enter the house as she has been damned – she has been condemned (‘Son scomunicata’).

It is fascinating that the two female dancers who arrive with Alfio are horses; they seem to have mastered just the right movements. But it is Stefano Meo’s voice as Alfio that really impresses, strong over its entire range.

Dramaturgically, the contrast between the ‘Easter Hymn’ and the ensuing (fourth) scene between Lucia and Santuzza is spectacularly managed. A Cross is on high with ribbons around it (which reminded me of the May Pole, a nicely Pagan image). The chorus is on top form as is Santuzza as she leads them in the ‘joys of Heaven’. The massive contrast to Mamma/Santuzza in this production, the stage dark, the characters all dressed in dark (plus, both have dark hair) is impressively made. Sangassi shines at ‘Voi lo sapete, o mamma’ her voice dark, never harsh; and how darkly shaded is Marchi’s ‘Miseri noi”.

The role of Lola is taken by mezzo Alessia Nadin, who possesses a lovely, light voice, a great contrast and for sure a singer to watch (she had also sung Lola at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna in December 2019; interesting to see her repertoire includes Adonella Francesca da Rimini, which she sang at La Scala in 2018).

The confrontational duet between Alfio and Santuzza carries full weight; and his lust for vengeance fully believable, Meo’s voice beautifully powerful.

Four lines of light descending to an otherwise gloomy stage forms the bleak backdrop for a chorus, clad entirely in black, on their way home; another finely judged contrast to the ‘brindisi’ scene. Warring factions, alpha male posturing and a Lola who looks in equal parts fascinated and satisfied with the unfolding drama, complete a glowering verismo atmosphere, impeccably mirrored from the pit. Turiddu’s request for a blessing from his mother (the passage that begins ‘Mamma, quel vino è generoso …’) is incredibly touching; Villari has the vocal strength, too

There is a rather unfortunate mistake in the otherwise excellent subtitles: instead of ‘Santuzza,’ we get ‘Poor Santa will be left deserted’. Nooooo, not at Christmas, surely ….

Flippancy aside, this is a powerful reading; that it is available to anyone with an internet connection for free is a gift.

Moving to the Pagliacci after an intermission that includes a guided tour of backstage, we move to Serena Sinigaglia’s production. Tonio enters in front of a wooden raised stage on a stage – he does a high five with a stagehand transporting the crosses from Cavalleria across the stage, which is a nice touch. This is Prologue as transition. Above a whole lot of stage noise, Stefano Meo embarks on a strong, lyrical ‘Un nido di memorie’ (‘Deep-embedded memories’); and how cantabile from both singer and orchestral strings is ‘E voi, putosto che le nostre povere’ (‘Mark well, therefore, our souls’); amusingly, it is a member of the ‘production team’ who ushers him off-stage. A second stage is visible in the middle of the stage proper, raised and the scene for the play later in the opera; it is surrounded by what looks like high grass.

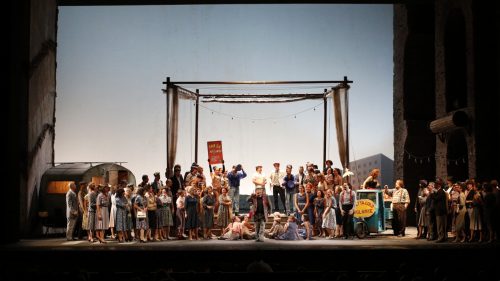

I must assume the trumpet announcing the arrival of the players is deliberately sloppy and approximate; but more interesting is the way Chaslin changes the orchestral gear from the pervasive darkness of Cavalleria to the party-carnival atmosphere of Pagliacci. The players are brilliantly dressed in the commedia dell’arte tradition, their gestures those of puppets. Canio, dressed in pointed black hat and oversized clown clothes, offers a fabulous invitation to the crowd to join them later. All credit to the chorus master Alberto Malazzi for the chorus’s sound (they are simply superb at the evocation of bells ringing for Vespers) and the director Serena Sinigaglia for managing the space so well.

Carmen Solis is a superb Nedda; her long scena is a masterclass in verismo singing. Her voice has a strong core (it can probably cut through any orchestra) and throughout she projects a hint of the histrionics that are to unfold. Interestingly, Solis was a substitution for Carmela Remigio, who was originally slated to sing the role. Her Silvio, Vincenzo Nizzardo, is a typically Latin red-blooded male figure; his baritone is strong, their voices well suited together; importantly, they ratchet up the intensity with their upwardly-reaching phrases (equally important to notice that the orchestra, while tracking that passion perfectly, is also texturally clear).

When it comes to Canio’s ‘Recitar! … Vesti la giubba,’ Stefano La Colla not only has the voice but a rather disconcerting realism when it comes to hysterical laughter. In the background, cast members slowly mime scythes cutting through the grass (the reference to Death’s scythe unmistakable).

The play itself gives the Beppe/Arlecchino, Paolo Antognetti, a chance to shine; he sings, miming a lute, brilliantly. Canio dons a pair of dog’s ears that could easily be those of a rabbit or a hare, but the commedia dell’arte point is made. The ‘puppet show’ is directed in masterly fashion, as is the denouement: the shift from high comedy to tragedy (and indeed back again) is fabulously managed, and again it is the shifts in the orchestra that drive the action so inexorably.

The finest of the OperaStreaming presentations so far.

Colin Clarke

For more about Teatro Comunale di Bologna click here.