France Mozart, Die Zauberflöte (La Flûte enchantée, The Magic Flute): Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Opéra national de Paris / Cornelius Meister (conductor). Performed at – and livestreamed (directed by Jérémie Cuvillier) – from Opéra Bastille, Paris, on 22.1.2021. (JPr)

France Mozart, Die Zauberflöte (La Flûte enchantée, The Magic Flute): Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Opéra national de Paris / Cornelius Meister (conductor). Performed at – and livestreamed (directed by Jérémie Cuvillier) – from Opéra Bastille, Paris, on 22.1.2021. (JPr)

Production: (co-production with the Festspielhaus, Baden-Baden)

Director – Robert Carsen

Set designer – Michael Levine

Costume designer – Petra Reinhardt

Lighting designer – Peter Van Praet

Video – Martin Eidenberger

Dramaturgy – Ian Burton

Chorus master – Alessandro Di Stefano

Cast:

Tamino – Cyrille Dubois

First Lady – Tamara Banješević

Second Lady – Kai Rüütel

Third Lady – Marie‑Luise Dressen

Papageno – Alex Esposito

Papagena – Mélissa Petit

Sarastro – Nicolas Testé

Monostatos – Wolfgang Ablinger‑Sperrhacke

Pamina – Julie Fuchs

Queen of the Night – Sabine Devieilhe

The Speaker – Martin Gantner

First Priest / Second Armed Man – Michael Nagl

Second Priest – Franz Gürtelschmied

First Armed Man – Lucian Krasznec

Three Boys – Nodarian Maxime, Joséphine Roubaud, Clément Bee

An impressive Goldilocks (just right) lockdown Die Zauberflöte in so many ways: funny (though difficult without audience reaction!) and not-too serious, sufficiently light and not-too-dark.

This 1791 Singspiel Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) in two acts was the culmination of Mozart’s increasing involvement by the composer with Emanuel Schikaneder’s theatrical troupe that since 1789 had been the resident company at the Freihaus-Theater auf der Wieden in Vienna. Mozart was a close friend of one of the singer-composers in the troupe, Benedikt Schack (the first Tamino), and had contributed to their compositions which were often collaboratively written. A year earlier in 1790, Mozart participated in Schikaneder’s opera Der Stein der Weisen (The Philosopher’s Stone) and just like Die Zauberflöte that also was a fairy tale opera, and almost its precursor since it employed much the same cast in similar roles. Die Zauberflöte, as Mozart intended, is noted for its prominent Masonic elements; both Schikaneder and the composer were Masons and lodge brothers. The opera depicts the triumph of reason over despotism and is also influenced by Enlightenment philosophy and can be regarded as an allegory propounding enlightened absolutism. The Queen of the Night is the dangerous form of liberalism, whilst her antagonist Sarastro is the reasonable sovereign who rules with paternalistic wisdom and free-thinking insight. The libretto also contains a racial stereotype in the form of Monostatos (who makes unwelcome advances to Pamina mainly because he is a Moor and black) and equally dreadful misogyny with all women regarded as subservient to men.

Robert Carsen’s Die Zauberflöte was first seen at the Baden-Baden Easter Festival in 2013 and was first staged in Paris the following year and it confronts these issues head on. He shows us how love reigns supreme, light triumphs over dark, life over death, and enlightenment over obscurantism. That is what we see, although as regards Schikaneder’s libretto (as in the English subtitles) we still hear Monostatos say ‘Am I to forego love because I am black’ and lust over Pamina because ‘Her whiteness is so lovely’. Then we must listen to how ‘A man is strong-minded, he thinks before speaking’ (apparently women don’t!) and ‘Without a man, women stray from their rightful sphere’.

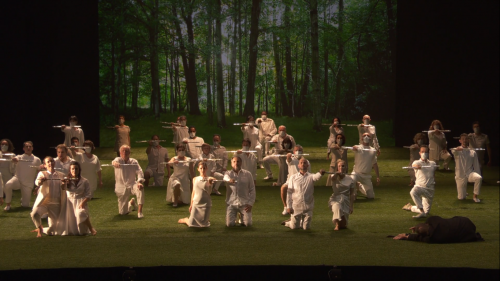

Carsen doesn’t shy away from Die Zauberflöte’s darkness and bases his approach on the fact that he has found sixty mentions of death and two attempted suicides in the work. Since Carsen believes that in the West we have trouble dealing with death: he shows how Tamino and Pamina face up to it, despite its inevitability, right from the start as the white-suited Tamino emerges from a freshly dug grave into a forest glade. There is AstroTurf on the floor of the stage and a woodland projected at the back which we will see – on and off – throughout the opera, though through differing seasons. Depending on the scene, we will see how this upper realm is connected to an underworld – with its dirt floor often littered with coffins and skeletons – by three steep stage-high ladders.

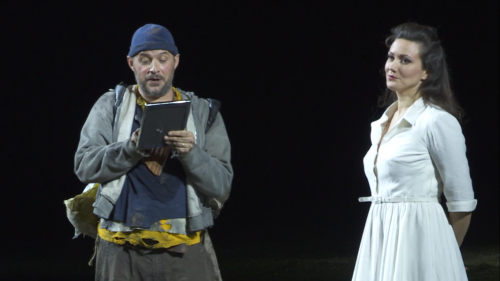

Papageno enters looking like a rough sleeper carrying his sleeping bag on his back and with a cooler for his birds. The Three Ladies and the Queen of the Night are mourners at a burial and are in haute couture black, veiled, and wearing dark glasses. As for ‘the evil snake’ it looks more like an extraordinarily long earthworm and it gets shot by the Three Ladies. Instead of a padlock to close Papageno’s mouth and stop him lying the Third Lady uses a remote key fob complete with the appropriate sound effect, When Tamino see Pamina’s portrait, she is shown walking in the forest before there is a closeup on the screen at the back of the stage. The flute and glockenspiel are passed up from the orchestra pit.

The Speaker, Sarastro and his acolytes are also veiled and in mourning, though the opera’s problem with misogyny is partly overcome by having women singing in the temple as well as the men in black. Carsen want us to realise Pamina is being tested as much as Tamino, and the Queen of the Night is in on the whole thing right from the start. So, for instance, she is there – silently – with Sarastro during ‘In diesen heil’gen Hallen’, unacknowledged by Pamina who she will veil with obvious maternal concern. Also, the Three Ladies are never too far away either. As for the thorny problem of Monostatos, at least visually? It is dealt with by making him the gravedigger and giving him one sublime moment in Act II when he picks up a skull and is made to grumble ‘To be or not to be on this journey?’.

Therefore, you will appreciate that there is little of the expected ‘magic’ or traditional rituals and certainly no cute animals. Papagena makes her first appearance emerging from a coffin during Papageno’s trial of silence not as an old crone, but as a skull-faced corpse-like ‘bridezilla’. There is no balloon for the Three Boys who are just football-mad boys, though they are delightfully voiced by two boys and a girl! They change their appearance depending on the character they are helping and though this is usually Tamino, they wear white dresses to match Pamina, and when preventing Papageno’s suicide, they have they own backpacks and each carries a cool box. The trials by fire and water seem to involve a crematorium and a waterfall. Carsen throws into this mix some hand gestures and clapping; whilst at the end – as ‘The sun’s rays have chased away the night’ – everyone who has got through the initiation has earned his or her own flute and even Monostatos is now reconciled with everyone in the brother- and sisterhood.

The cast was impressively charismatic though not that well-known to me. Beginning with the men (for no particular reason!) Cyrille Dubois’s ‘Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön’ had conviction and its final phrases were the culmination of a heartfelt arc. There was so much grace and beauty to his singing – which with an innate nobility to his timbre – all helped make this Die Zauberflöte the spiritually transcendent experience it must be. Over the years I have seen and heard many wonder Papagenos, but Alex Esposito was as good as any and he ever made a misstep either with his acting or singing. He has a large, well-projected bass-baritone voice and his performance was witty, and he showed impressive physical dexterity and his bird catcher helped enormously to bring Carsen’s production to life. Martin Gantner imbued The Speaker with a certain profundity and Nicolas Testé was an outstanding Sarastro. Due to his sombre tone and cavernous bass notes Testé brought gravitas to all Sarastro’s pronouncements, every word clear and resonant, and he clearly was an inspirational leader. Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke’s sturdily sung Monostatos impeccably balanced his character’s appalling behaviour and racial identification as a Moor to make his character less despicable than he can be. (Ablinger-Sperrhacke is unlikely to sing Alberich in Wagner’s Ring but his Monostatos reminded me very much of that cunning dwarf.)

The female voices were just as strong: Sabine Devieilhe was an excellent Queen of the Night who was dignified, haughty, ambitious, yet – thanks to Carsen – surprisingly motherly. Devielhe’s highest notes were astonishingly pin sharp during the staccati of its famous aria ‘Der Hölle Rache’ (‘Hell’s vengeance’). The Three Ladies (Tamara Banješević, Kai Rüütel, and Marie Luise Dressen) were vocally very well-balanced and Mélissa Petit’s Papagena was charming even as a zombie and her duet (‘Pa… pa… pa…’) with Papageno was one of the highlights of this Die Zauberflöte. Julie Fuchs’s Pamina was a strong stubborn woman who faced up to Monostatos with determination and vigour. Her Act II aria of unrequited love ‘Ach, ich fühl’s, es ist verschwunden’ (‘Ah, I feel it, it is vanished’) was sincere and deeply sad and she exhibited exquisite breath control, vocal agility, and a secure top to her voice.

The chorus made a significant contribution and the German conductor Cornelius Meister (only weeks after his New Year’s Eve Vienna Die Fledermaus click here) conducted a very vibrant and fleet-footed performance that did not seek any new revelations, yet avoided any longueurs, and was able to enhance Carsen’s direction by relishing – along with his masked musicians – the music’s symphonic qualities. This was from the opening three chords of the overture (during which we saw a film of life backstage at the Opéra Bastille) to the opera’s triumphant ending. Meister was another conductor I have seen recently who did not need a score for a full-length opera, how did he manage that in Die Zauberflöte, especially with all the dialogue?

Jim Pritchard

For more about Opéra national de Paris click here.