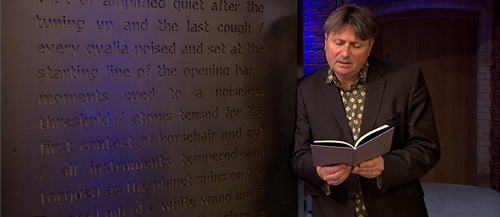

United Kingdom The Hallé Winter Season, Episode 3 – The Event Horizon: Simon Armitage (Poet Laureate), Jess Gillam (saxophone), The Hallé / Jonathan Bloxham (conductor). Broadcast from Hallé St Peters, Manchester, 14.1.2021. (CS)

United Kingdom The Hallé Winter Season, Episode 3 – The Event Horizon: Simon Armitage (Poet Laureate), Jess Gillam (saxophone), The Hallé / Jonathan Bloxham (conductor). Broadcast from Hallé St Peters, Manchester, 14.1.2021. (CS)

(c) The Hallé

Simon Armitage – the event horizon

Copland – Quiet City

Hannah Kendall – Where is the chariot of fire? (world premiere)

Glazunov – Concerto for alto saxophone

Simon Armitage – Evening

Ravel – Mother Goose (suite)

event horizon n. (a) Physics the boundary of a region in space-time having the property that no event within that region can have a causal relationship with any external future event; esp. such a boundary associated with a black hole, beyond which neither electromagnetic waves nor matter can escape; (b) figurative a point of no return or at which something is not perceptible or knowable.

I don’t know if the two definitions of the phrase ‘event horizon’ offered by the Oxford English Dictionary were in Simon Armitage’s mind, or subconscious, when he fulfilled a commission for the opening of Hallé St Peters – the new recording, rehearsal, education and performance venue for the Hallé Orchestra in Ancoats, Manchester – in November 2019, but the poem that the Poet Laureate presented at the opening of this broadcast concert (the third in the orchestra’s Winter Series) is titled the event horizon. The poem is in fact incorporated into the physical structure of the building in the form of a letter-cut steel plate situated in the entrance to the auditorium, the ‘event horizon’. Rather than relating to either of the OED’s definition, the poem seems to me to describe and embody a suspended moment in time, between silence and sound, and to make palpable the phenomenal character of the experience – the ‘qualia’ – of waiting for music to emerge from unheard abstraction into temporal tangibility, or as Armitage puts it:

till that

greenflash of sound / the yaw and roll

as we’re pitched into music / tipped to

where raw music comes pitching

into the soul

The gentle pentatonicism of the strings at the start of Aaron Copland’s Quiet City breaks softly through Armitage’s closing words, bringing their meaning into being. This one-movement work for cor anglais, trumpet and strings derives from incidental music that Copland wrote for an unsuccessful and now forgotten play by Irwin Shaw. The play dramatises the internal conflicts of the middle-aged, half-Jewish Gabriel Mellon who has abandoned his youthful dreams of being a poet, opting instead for a socially and financially advantageous marriage and a successful business career. Troubled equally by recollections of his jettisoned artistic aspirations and a sense of responsibility to his perennially disenfranchised employees, during his dark nights of the soul Gabriel begins to believe that he can hear music – played by his brother, David, is a jazz trumpeter. He imagines that what he hears is “the night thoughts of many different people in a great city” and the music comes to represent Gabriel’s lost idealism, love and fulfilment.

The dialogues between the solo trumpet and cor anglais powerfully capture the Hopper-esque ‘urban loneliness’ that Shaw evokes, and which so many are feeling at this current time of isolation, restlessness and drift. The solo playing of Thomas Davey (cor anglais) and Gareth Small (trumpet) is beautiful, the cor anglais contemplative, wistful but not sentimental, the trumpet more forthright, urging and challenging. Conductor Jonathan Bloxham, making his debut with the orchestra, coaxes a sweetness, and sometimes a surprisingly sumptuous fullness, from the Hallé strings. The music feels unhurried, but flowing and flexible, and the listener is drawn into the embracing sound-world. Towards the close, a nervous agitation inflects the trumpet’s interjections, but this is assuaged by the tenderness of the cor anglais and strings, and at the close there is a sense of having journeyed and found a calm point of rest, as if something lost has been regained.

Poetry is at the heart of this programme. Hannah Kendall’s Where is the chariot of fire?, which was commissioned by the Hallé for this concert, takes its title from a line in Lemn Sissay’s poem, ‘Godsell’ – a line which derives from the Old Testament’s second book of King’s where the prophet Elijah is described as being raised up to heaven by a whirlwind-powered ‘chariot of fire’.

Any fiddle player who has tried to play and sing at the same time will know that it’s not as simple as it sounds. In Where is the chariot of fire? Kendall requires the players to hum in unison with their bowed notes and make vocal whispering sounds. The sonic experimentation is developed through coloristic scoring incorporating piano, harp, harmonica, tuba, side-drum and the Latin American guiro (first heard in a European orchestral score in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in 1913); the special positioning of particular instruments in that hall; and, through the incorporation of two wind-up music boxes which play the melodies of ‘You Are My Sunshine’ and ‘Carrying You’.

In conversation with Bloxham, Kendall explains that when the pandemic left her stranded in the UK for six months, cut off from her book collection back home in New York, the only book that she had with her was a collection of poems by Sissay. ‘Godspell’ which inspired Where is the chariot of fire? assimilates violent biblical imagery: Armageddon, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, demonised pigs, the valley of the shadow of death, a plague of locusts and a burning bush. Responding to such tumult and turmoil, the music conjures flashes of motivic fire that demand tremendous precision and incisiveness from the Hallé players. Kendall alternatives virtuosic explosiveness with contemplative intensity, the latter never serene, always probing and roving. There aren’t many duets for 15-note music box and violin, but at the close leader engages in a tense dialogue with the former’s rendition of ‘Deep River’, the eerie, repressed energy released in the ripping solo violin up-bow with which the six-minute work closes, expressing the hope for better things to come that Kendall responds to in Sissay’s poem.

‘Paris between the wars was a powerhouse for artistic innovation.’ So, the programme note for Glazunov’s Concerto for alto saxophone and strings tells us. Unfortunately, Glazunov didn’t really tap into the zeitgeist in his 1934 Concerto, which was written for the American saxophonist Sigurd Raschèr. It was the composer’s last work and does not make so much as the slightest nod in the direction of the way the instrument was being used in the popular and jazz music of the day.

Readers might sense that this is not one of my favourites: and I confess that I find it melodious but unmemorable. However, on this occasion soloist Jess Gillam invests the music with a light graciousness that was utterly beguiling. Her tone is wonderfully focused and clean, with warmth in the middle, purity higher up and depth below. She shapes the long, fluid lines of the initial Allegro moderato episode with a lovely suppleness, while the rapid passagework was vivacious and dynamic. The Hallé musicians and Bloxham respond alertly and engagingly to Gillam’s song, especially in the reflective central section. Gillam infuses the cadenza with a poignant melancholy but emerges with lightness into the dancing fugato with which the Concerto concludes. In the latter all is airy and chirpy. Fluttering saxophone trills are matched by tip-toeing string staccatos; rhetorical playfulness from the saxophone prompt assertive repartee from the orchestra. Gillam races mischievously to the close but Bloxham has the fun firmly under control.

Bloxham impresses in the suite from Ravel’s Mother Goose. He makes the music feel like a treasure chest of the most exquisite jewels, each one a different, rare hue, glinting with a sharp sparkle; each one precious, weightless, magical. Bewitching timbres, pianissimo delicacy, unwavering textural clarity: this is superb musical storytelling by the Hallé.

Ravel’s suite is preceded by Armitage’s reading of his poem ‘Evening’, which has its own (in the poet’s words) ‘West Yorkshire magic realism’. ‘I have promised not to go far’ explains the adolescent poet-speaker, only to find on his return home that he has become an adult – a husband and a father. There is a Keatsian wistfulness here which is tempered by a carpe diem scent that emits a powerful uplifting energy and ‘ambition’ – much-needed when our own ‘event horizon’ seems imperceptibly distant and fragile.

Claire Seymour

This concert is available to view (£) until Wednesday 14th April 2021 click here.