Russian Federation Myaskovsky. Dialogues – A Dialogue with Epoch: Klavdia Bashkirtseva (soprano), Alexander Trofimov (tenor), Sverdlovsk Philharmonic Quartet, Sverdlovsk Philharmonic Choir, Ural Youth Symphony Orchestra / Alexander Rudin (conductor). Livestreamed on the Virtual Concert Hall from the Sverdlovsk Philharmonic Hall, 9.3.2021. (GT)

Russian Federation Myaskovsky. Dialogues – A Dialogue with Epoch: Klavdia Bashkirtseva (soprano), Alexander Trofimov (tenor), Sverdlovsk Philharmonic Quartet, Sverdlovsk Philharmonic Choir, Ural Youth Symphony Orchestra / Alexander Rudin (conductor). Livestreamed on the Virtual Concert Hall from the Sverdlovsk Philharmonic Hall, 9.3.2021. (GT)

Myaskovsky – String Quartet No.13 in A minor, Op.86; Cantata-Nocturne ‘The Kremlin at Night’ Op.75; Symphony No.17 in G minor, Op.41

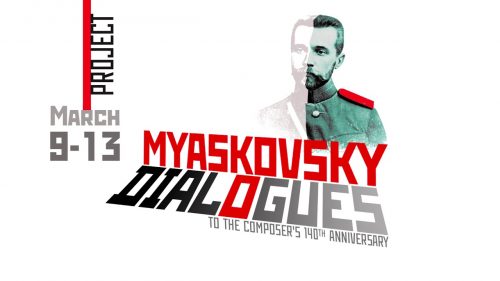

This year marks the 140th birth anniversary of the Russian composer Nikolay Myaskovsky, and much to their credit the city of Yekaterinburg in the Urals is celebrating his legacy as a composer, teacher, critic and administrator in the composers’ union. Myaskovsky (1881-1950) wrote 27 symphonies, 13 string quartets, 9 piano sonatas, two concertos, each for violin, and cello, and two cello sonatas, plus 150 songs and romances. His students included Khachaturyan, Kabalevsky, Mosolov, Knipper, Shebalin, Khrennikov, and Boris Chaykovsky, plus another 70 others. A unique aspect of his teaching at the Moscow Conservatoire was his independence of thinking, he encouraged his students to find their own voice, and avoid copying styles. He was also a noted music critic and assisted in developing contacts with Universal Music Publishing in the 1920s inviting composers like Bartók , Hindemith, Milhaud, Reger, Casella and others to the USSR during that decade. His music was very popular in the West in the 1920s and 1930s, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra played his works 55 times up to the Second World War. His Thirteenth Symphony was premiered in Chicago, and the Twenty-First Symphony was commissioned by the Chicago ensemble. Following the 1948 Soviet Composers’ Congress where he was denounced as a formalist and decadent, Myaskovsky’s music was rarely performed both in Russia and the West. Only in the 1980s was his music revived and all his orchestral works were recorded by Svetlanov. Shostakovich named Myaskovsky one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century.

If more recordings are appearing, both of his symphonies and chamber works, it is still rare to hear his music in the concert hall. Russian orchestras are more often scheduling his symphonies, but this Festival devoted to Myaskovsky is the first to celebrate his music anywhere; there have been cycles of the piano sonatas performed in Moscow, but no major events. An advantage of this festival is a series of dialogues between musicologists and performers in the weeks prior to the concerts, including Gabriel Prokofiev, the grandson of the great composer who was a lifelong friend of Myaskovsky.

Yekaterinburg is a huge city boasting a music conservatoire (named after Musorgsky), a first-class opera and ballet theatre and two symphony orchestras. The city is in the process of building a ‘state of the art’ concert hall (more of which later) and indeed the ‘Myaskovsky Dialogues’ is only one of several music festivals taking place currently; the Bach Festival has been going on since January through to April, and shortly another music festival will commence. The Ural Youth Symphony Orchestra was formed in 2006 and has toured extensively both in Russia and to Europe and their debut recording on Naxos of two Myaskovsky symphonies received an award from ICMA in 2020.

The first of three concerts took place when the city was snowbound and at a temperature of minus 10, however I am assured that the Russian public’s enthusiasm is unabated, and they turn up in all weathers. The Philharmonic, following six months of lockdown restarted their concerts several months ago and have been enjoying well attended audiences. A feature here is the streaming of all the concerts throughout the Urals region to schools, libraries and online to subscribers. These events are being supported by the Ministry of Culture and several private sponsors.

The Sverdlovsk Philharmonic String Quartet of Alexander Zinchenko (first violin), Yulia Maximova (second violin), Vladimir Zinchenko and artistic leader Alexey Kudinov (cello) were formed in 2010 from members of the Ural Philharmonic Orchestra and have their own series of subscription concerts and appear regularly on TV and radio. They were prize-winners of the 2015 chamber music competition in Prague and have toured to China and Germany in recent seasons.

In the valedictory Thirteenth String Quartet, the first movement (Moderato) opened on the second violin, and picked up more extensively on the cello, with a vivid folk tune, which on the first violin became noble, then a secondary idea develops into a toy-like fugue becoming a chant-like melody explored by all four players before disappearing wistfully. In the second movement (Presto fantastic) the idiom was bright and dashingly exciting, played with great tension, yet there emerged a theme which is almost macabre, sounding mysterious and sinister like a walk at midnight in a graveyard and ending in a terrible sprint into dark terror. The third movement (Andante con moto cantabile) was played at a mourning pace, before opening up a broad song-like theme which was splendidly performed by Kudinov on the cello. The opening to the finale (Rondo-sonata, molto vivo energico) was brilliantly played on all four instruments, mixing powerful ideas with elegiac undertones – all sounding powerful and decisive. There emerged ideas from the previous movements injecting lyricism and a profoundly brilliant finish. It is clear this is a much-neglected piece and it was superbly performed by a virtuoso ensemble.

Another forgotten piece is ‘The Kremlin at Night’ Cantata-Nocturne based on texts by the Russian symbolist poet Sergey Vasilyev and is among the finest pieces in this last stage in Myaskovsky’s career. Composed in the summer of 1947 when he was recovering from illness, it is one of the brightest pieces of music that Myaskovsky wrote. The opening Introduction was suspenseful on the violins, and there was beautiful melody from the two horns, with shimmering harmonies from the cymbals and harp, and the mixed choir’s singing was muted yet charming. In the second movement, the Aria for tenor and chorus, there was some superb singing, energetic and emotional in its rich harmonies. The chorus was deeply elegiac, and one was reminded somewhat of Delius and Vaughan Williams, yet this was quite exceptional if one reminds oneself of Prokofiev and Shostakovich in their choral writing. In the Aria with soprano, the idiom was poetic with captivating singing from Klavdia Bashkirtseva ending on a magically high C, before the bass clarinet led into the Chorus finale where there were some quirky ideas on woodwind, against hushed singing by the ladies’ chorus, and a marvellously suspenseful close. This is a little masterpiece and seems to anticipate the vocal works of Georgy Sviridov of the sixties and seventies.

Composed in 1937, the Seventeenth Symphony comes shortly after the popular Sixteenth Symphony which was full of winning melodies. The Seventeenth is reflective and somewhat dark, yet there emerge passages of great beauty. There is a story about neglected symphonies, notably that of Rachmaninov’s First which was forgotten after its disastrous premiere, however, it is now regarded as popular after the second premiere of 1945. Myaskovsky’s symphonies were very popular in the USA in the 1930s, yet have hardly been heard of since, despite recordings appearing in recent decades. This symphony was at the same time as Shostakovich’s Fifth and shares the same glorious musical ideas as his colleague, written though by a different voice: there is no parody or sarcasm in Myaskovsky’s music. The Seventeenth opened with a great theme on strings and backed up by marvellous playing for the oboe and flute and a secondary more ambitious idea is picked up and the drama returns almost like we are witnessing a struggle between good and evil. There is top-class playing by these young musicians, and the extended first movement closed with great energy and some terrific playing.

The second movement, (Lento agitato – Allegro molto) is deeply reflective with an attractive folk tune emerging in a passage from the violins heard against the solo horn, and a superb bass clarinet solo was followed by a delightful idea in the strings accompanied by the harp and clarinet. How much this orchestra feels for this music is evident from their smiles and this orchestra has some promising woodwind and brass players. In the Allegro, poco vivace, a superb idea from the oboe is heard followed by lively dramatic playing; this orchestra sounds quite loud against the acoustics of this rather small hall, and there was wonderful playing in the cantabile section and a magical idea emerged on the woodwind before the climax. In the finale (Andante. Allegro molto animato) the horns introduced a rather funeral chorale, sounding dark and grimacing in the strings, yet the first violins opened up a bright optimistic idea which sounded glorious from the full orchestra. In the final section, the polyphonic form in a fugue led to an organic whole full of great drama and excitement and concluded with a brightly optimistic coda.

This was a tremendous performance of a long-neglected symphony, and many thanks are due to the musicians and organisers of this very promising festival celebrating the 140th anniversary of Myaskovsky’s birth.

Gregor Tassie

For more about ‘Myaskovsky Dialogues’ click here.