Austria Lehár, The Merry Widow (Die lustige Witwe): Soloists, Dancers of Vienna State Ballet, Chorus and Orchestra of the Volksoper Wien / Alfred Eschwé (conductor). Volksoper Wien, Vienna, 3.9.2021. (RP)

Austria Lehár, The Merry Widow (Die lustige Witwe): Soloists, Dancers of Vienna State Ballet, Chorus and Orchestra of the Volksoper Wien / Alfred Eschwé (conductor). Volksoper Wien, Vienna, 3.9.2021. (RP)

Production:

Director & stage designer – Marco Arturo Marelli

Costumes – Dagmar Niefind

Choreographer – Renato Zanella

Chorusmaster – Thomas Böttcher

Cast:

Hanna Glawari – Ursula Pfitzner

Count Danilo Danilowitsch – Ben Connor

Baron Mirko Zeta – Sebastian Reinthaller

Valencienne – Julia Koci

Camille de Rosillon – David Sitka

Njegus – Georg Wacks

Kromow – Heinz Fitzka

Olga – Heike Dörfler

Bogdanovitch – Daniel Strasser

Sylviane – Klaudia Nagy

Raoul de St. Brioche – Christian Drescher

Vicomte Cascada – Michael Havlicek

Pritschitsch – Gernot Kranner

Praskowia – Sulie Girardi

Dance soloists – Kristina Ermolenok, Gleb Shilov

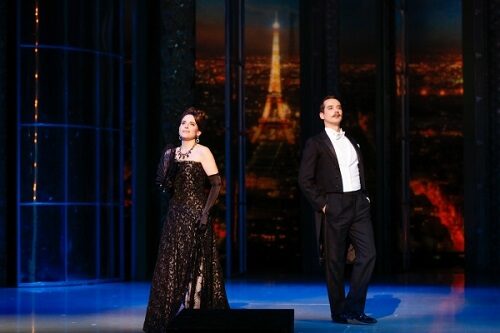

Time stood still when Ursula Pfitzner as the glamorous Hannah Glawari began to dance with Ben Connor, her Danilo, as Act I ended with the violins playing the beloved waltz that courses its way through Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow. There were other such moments to follow in the Volksoper Wien’s elegant production full of wit, laughter and beautiful music, but those few seconds were enchanting.

Since its premiere at Theater an der Wien in 1905, The Merry Widow has achieved worldwide popularity with performances numbering in the hundreds of thousands. It is the story of young widow from Pontevedro whose husband died after a few days of marriage and left her very wealthy. All of Pontevedro, especially the embassy staff in Paris where Hanna has moved to partake of its delights, want her to marry a Pontevedrian to keep her money safe and to prop up the country’s shaky finances.

The obvious candidate is the dashing Count Danilo Danilowitsch, but there is a catch: Hanna and Danilo were once in love, but his family objected to his marrying a penniless girl. Danilo refuses to pursue Hanna now that she is rich, and she likewise demurs unless he says ‘I love you’, words that he has vowed to never utter again to her.

Amidst the backdrop of sexual peccadilloes, a never-ending round of parties and the men’s regular visits to Maxim’s (a ‘place to take ladies but never one’s wife’), the lovers are reunited. The men who were desperate to marry Hanna flee the scene when she announces that if she marries, she will lose her fortune. It prompts Danilo to say the magic words, and he ends up with the woman he loves and her money.

The intrigues take place in a grand Art Nouveau apartment in Paris with sweeping views of the city, including the Eiffel Tower. With the slightest of reconfigurations, the stage is transformed into the Pontevedrian embassy, Hanna’s apartment and its garden. The glittering dresses and architectural coiffeurs of the women would seem to be from the 1960s, but there is a certain timelessness to the production. If the national costumes of Pontevedro are not bright enough, there are the flouncy skirts of the Grisettes from Maxim’s.

The glamor and sophistication of Pfitzner’s Hanna would seem to belie her humble origins. There were times when Pfitzner’s voice sounded a bit frayed, but all was forgotten as she spun out a bewitching ‘Vilja’. Sparks flew whenever Pfitzner and Connor were on stage together in spite of, or perhaps due to, his boyish and hangdog demeanor. Connor’s matinee idol looks and his warm lyric baritone go hand in glove.

Julia Koci was a delightful Valencienne who, in spite of her protestations that she is a respectable wife, amuses herself with a flirtation with Camille de Rosillon. Smitten with Valencienne, David Sitka’s Camille is little more than a lapdog following her everywhere, but his beautiful lyric tenor is the real thing. Presiding over the embassy was Sebastian Reinthaller, as courtly, astute and opportunistic as any of the men.

The most laughs came from Georg Wacks’ Njegus, Zeta’s major domo, due to his perfect combination of deadpan demeanor, expert comic timing and physical agility. And in what is little more than a cameo role, Sulie Girardi as Praskowia captured the charm, grace and elegance of a bygone era.

Lehár’s waltzes and melodies were lighter than air under the baton of Alfred Eschwé. The wonderful ensembles – the men rhapsodizing on the charms of Maxim’s and the Grisettes kicking up their heels dancing the cancan – sparkled like champagne. From beginning to end, the Volksoper’s The Merry Widow was a delight.

Rick Perdian