United Kingdom Wagner, Lohengrin: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden / Jakub Hrůša (conductor). Royal Opera House, London, 19.4.2022. (CC)

United Kingdom Wagner, Lohengrin: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden / Jakub Hrůša (conductor). Royal Opera House, London, 19.4.2022. (CC)

Production:

Director – David Alden

Revival director – Peter Relton

Set designer – Paul Steinberg

Costume designer – Gideon Davey

Lighting designer – Adam Silverman

Video designer – Tal Rosner

Movement director – Maxine Braham

Chorus director – William Spaulding

Cast included:

Lohengrin – Brandon Jovanovich

Elsa von Brabant – Jennifer Davis

Ortrud – Anna Smirnova

Friedrich von Telramund – Craig Colclough

King Heinrich I – Gábor Bretz

Herald – Derek Welton

First follower of Telramund – Elgan Llŷr Thomas

Second follower of Telramund – Thando Mjandana

Third follower of Telramund – Matthew Durkan

Fourth follower of Telramund – Thomas D. Hopkinson

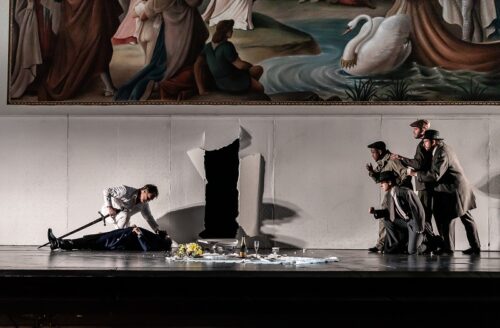

The first run of this Lohengrin was covered by my colleague Jim Pritchard (review click here). David Alden’s production continues to intrigue, with its skewed perspectives on buildings (where the chorus sometimes appears, or brass). We are clearly in wartime and there are coincidental allusions to current events in Eastern Europe. The only respite from the dark colours of both garb (costumes Gideon Davey) and Adam Silverman’s lighting are basically Lohengrin’s white suit, Elsa’s white wedding dress, the Persil-white bedroom (with its sole mural of the Swan Knight to remind us of where we – in theory – are), and a bed whose presence seems more threatening than inviting. Paul Steinberg’s sets seem to close in on the action, glowering menacingly, themselves a visual reflection of a fundamentally flawed society. The mural in question is actually August von Heckel’s Lohengrin’s arrival (in Brabant), sometimes known as ‘The arrival of Lohengrin in Antwerp’, from one of King Ludwig II of Bavaria’s castles and dating from later than the opera (1882/82).

There are odd moments that feel mishandled: Telramund’s bursting through a wall in the second act feels almost cartoonish. Of course, the use of the Nazi ‘Sieg Heil’ arm salute sits, presumably deliberately, uncomfortably – and, in the final stages, the hanging flags bring a Nazi rally to mind (albeit here adorned with a stylised image of a swan instead of a black eagle). Ortrud, alone in Act II at a desk under a strip light, is the very image of darkness: the light there seems the intruder onstage. The great success is through the video evocation of winged movement heralding the arrival of Lohengrin and his swan which is far better than any physical representation onstage I can remember: Tal Rosner’s video designs are not only state-of-the-art but perfectly suited to the ongoing drama. Lohengrin enters into a world of militaristic repression and yet – despite his garb – he is no angel himself, his gestures sometimes bullying or brutish.

The space of the opera house is used to phenomenal effect: chorus members at one point turn up in the stalls, intruding on our reality and merging stage and auditorium experience; Ortrud appears in a box toasting the stage with a glass (presumably of champagne); yet more brass at one point appear in other boxes, while an offstage – in the sense of yet another box – harp and cymbal perhaps indicate a stuffed pit. It works well, but what works best of all is the conducting of Jakub Hrůša, whose attention to detail, and ability to inspire his players, is without peer. The entrance of the woodwind in the Act I Prelude was the best I have heard it live (and better than most recorded); his brass hardly set a foot wrong all night, a remarkable achievement in this opera. He clearly hears the piece on the large-scale, too, with the result that choral climaxes veered towards the overwhelming. He works supremely well with his singers, balancing carefully and providing a truly natural flow to Wagner’s opera.

Musically, the evening belonged to the principals. Brandon Jovanovich is a true Heldentenor, with a ring to his voice, never-ending stamina and even a firm lower register. Alden’s production means he has to be physically agile as well as vocally, and Jovanovich not only succeeds, but his presence can dominate the stage with ease. He has the force for the great outbursts (‘Mein Vater Parzival trägt seine Kröne’ for example) but the sweetest, quietest top for those moments of magic Wagner allows.

His Elsa was Jennifer Davis, who had taken the role in the production’s previous incarnation. Davis (ex-Jette Parker) has all the right vocal resources for Elsa: purity of tone combined with an inner core of strength. Her character becomes even more sympathetic in Davis’s hands: we really feel that her final happiness was, for the short time it lasts, deserved, though our hearts plummet as it is wrenched away from Elsa by her ill-advised questioning of Lohengrin’s name.

Their adversaries were also cast from strength, particularly in the case of Anna Smirnova’s repellent Ortrud, reptilian of stance and a true incarnation of a Black Magic sorceress. It was one of the great assumptions of this role: if the militaristic setting reflects the darkness of the human soul exteriorised, Ortrud is the dynamic expression of that, setting in motion magic and emotions of the most destructive bent. Her performance was absolutely on a par with Jovanovich and Davis. Ortrud’s cackle – the only word for it – after she mentions the word ‘God’ said it all. Smirnova’s second duet with Davis’s Elsa provided some of the finest drama of the evening, and on a purely musical level was exemplary, the contrast between their voices perfectly judged.

American bass-baritone Craig Colclough replaced Kostas Smoriginas as Telramund (Smoriginas sang the Herald in the 2019 run), perhaps not quite Smirnova’s equal vocally or dramatically – but who could be? Gábor Bretz is a known, and justifiably admired, quantity, and his King Heinrich was finely delivered, while Derek Welton’s Herald was a fine, strong assumption that gave this character much more presence than one normally experiences.

The chorus, a collective character in its own right in this opera, was simply awe-inspiring. The Royal Opera Chorus on top form has to be heard to be believed, especially the force it can muster at top volume.

A great deal of publicity has been given to The Royal Opera’s Peter Grimes recently (sadly that is one I did not see); this Lohengrin deserves, too, to be lavished with the highest praise. Alden’s staging plays a huge part in reminding us of the power of Wagner’s 1850 score, a masterpiece in its own right.

Colin Clarke