United States Prototype 2023 [2] – Emma O’Halloran, Trade and Mary Motorhead: Kyle Bielfield, Marc Kudisch, Naomi Louisa O’Connell (performers), Novus NY / Elaine Kelly (music direction). Abrons Arts Center, New York, 13.1.2023. (RP)

United States Prototype 2023 [2] – Emma O’Halloran, Trade and Mary Motorhead: Kyle Bielfield, Marc Kudisch, Naomi Louisa O’Connell (performers), Novus NY / Elaine Kelly (music direction). Abrons Arts Center, New York, 13.1.2023. (RP)

Production:

Libretto – Mark O’Halloran

Director – Tom Creed

Electronic sound – Alex Dowling

Sound – Garth MacAleavey

Sets – Jim Findlay

Lighting – Christopher Kuhl

Costumes – Montana Levi Blanco

Irish composer Emma O’Halloran was the recipient of a Next Generation award in the 2018-2019 Beth Morrison Projects’ competition cycle, which was launched to help the organization stay connected to composers, singers and artists just emerging on the scene. Prior to entering the competition, O’Halloran was finishing her doctorate at Princeton University and never thought of composing an opera.

Segue to January 2023, when two of O’Halloran’s chamber operas, Mary Motorhead and Trade, are receiving their world premieres at the Prototype Festival. Both are based on plays by her uncle, the actor and award-winning Irish playwright Mark O’Halloran, who also wrote the librettos. Emma O’Halloran’s music is as true and honest as the characters that her uncle created.

Mary Motorhead tells the story of a woman who drove a knife through her husband’s head. Red O’Brien, a man on whom no fair wind ever blew, entered Mary’s life as if shot from a cannon. She loved Red, but after a while she stopped believing in him. He started to slap her around. Cutting open his head seemed to be the only way that she could find out what was going on inside it and whether she was there. For that, she’s serving six years in prison.

Mary doesn’t harbor any illusions about her life – little education, no real job since the factory closed, just making do – and quips ‘Give a girl enough rope, and she will hang herself’. That is her public history, but her secret history – what was going on inside her – is what’s important to her. Naomi Louisa O’Connell is electrifying as Mary, stalking about a prison cell as her story explodes out of her. Mary is a caged lion and combative as hell but with few regrets. She can, however, soften in a heartbeat, and it’s the fragility that makes her likable. You want her to be free and happy, which is her dream.

‘Trade’ in gay slang is the casual partner of a gay man who does not identify as gay and generally receives some sort of economic benefit in exchange for sex. On the face of it, that describes what’s going on in O’Halloran’s opera but, as is Mary Motorhead, it’s the intimate stories of the two men involved that are under the lens. Ostensibly, the older man is there for sex, but what he really wants to do, having been raised Catholic and all, is to make his confession. Father issues loom large for both men, especially in the case of the older man, and jump-started his awkward lunges towards honesty. After the older man’s father died, it turned out he was leading a secret life: a fire and brimstone Catholic at home with a mistress on the side. The son doesn’t want to live a lie, with the full picture of who he was emerging only after his death.

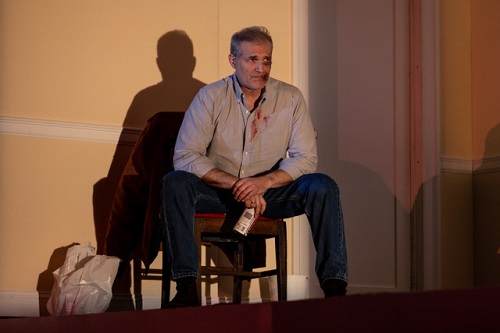

His first meeting with the younger man, whom he picks up at a public toilet, was just after his father died. The second is on the day he told his own son, who’s about the same age as the younger man, his secret. That’s why his face is a bloody mess, but he admits that he deserved it. The younger man in Trade with a shock of green hair is, in some ways, the male equivalent of Mary Motorhead – unemployed and aimless. The difference is that he has a daughter, Chloe, who anchors him. When he says his daughter’s name, it’s a burst of melody that the older man mocks. It’s not malicious but more an awkward attempt to pierce one of the few chinks in the lad’s armor.

Marc Kudisch’s older man is as stoic as he is wide-eyed about the moral issues of what he is doing. He is also amazingly unfazed about his leap into the unknown. A dull job, which he lost when the factory was taken over by foreign owners, may have suited him, but there is a lot going on beneath the surface of Kudisch’s character. His compulsive teeth cleaning is just one of the clues. Kudisch keeps the man’s libido at a low burn, but his new-found freedom has made him bold: he dares to tell the young man that he loves him. Kudisch keeps it simple and is never maudlin, even when pouring out his guts.

Kyle Bielfield’s younger man is all false bravura, but he is sure of his sexual potency. When he invitingly lies back on the bed, the young man smolders. These are also the only times that he is in control of the situation. The actor’s take on the young man is equal parts punk and boxer, and he unsuccessfully prevents the older man’s jabs from hitting home. When they do, the young man undergoes a catharsis. Bielfield’s emotional connection with his character was so intense, that he was still wiping away tears during the curtain calls.

The musical worlds that O’Halloran creates out of acoustic and electronic sounds for the two operas are as different as the stories they help tell. The soundtrack for Mary’s searing monologue is the hard-driving, jagged, heavy-metal sound that provided an escape for her as well as a nickname. There is anxiety, anger and frustration in the score, which fades only at the end when Mary reveals her hopes for the future. For Trade, O’Halloran composed music that was minimalist in style with the constant repetition of ever-evolving melodic fragments mirroring the back and forth of the two characters. The music expresses through sound what the men struggle to verbalize. Their demons are all found in the score, along with a hypnotizing erotic current that is ever present.

Elaine Kelly, the Resident Conductor and Chorus Director of the Irish National Opera, is a champion of new opera. With Novus NY, Trinity Church Wall Street’s new-music orchestra, she had the perfect partners with whom to craft O’Halloran’s seamless soundscapes of intertwining instrumental and electronic sounds.

In the program, O’Halloran writes that these aren’t the characters you find in traditional opera, but she is wrong about that. Murderous spouses (think Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk) and suppressed homoerotic tendencies (almost anything by Britten) are the stuff of which opera is made. The difference is that the characters that spring from Mark O’Halloran’s operas don’t die. Flawed as they are, there is hope that they will find some semblance of happiness in the future. Emma O’Halloran’s music makes their journeys all the more compelling.

Rick Perdian