United Kingdom Dukas, Elgar, Tchaikovsky: Daniel Müller-Schott (cello), Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Vasily Petrenko (conductor), Royal Festival Hall, London, 23.4.2023. (MBr)

United Kingdom Dukas, Elgar, Tchaikovsky: Daniel Müller-Schott (cello), Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Vasily Petrenko (conductor), Royal Festival Hall, London, 23.4.2023. (MBr)

Paul Dukas – The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

Elgar – Cello Concerto

Tchaikovsky – Manfred Symphony

On paper, this concert given by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Vasily Petrenko was just inspired; whoever came up with it clearly knew what they were doing. But it also left no room for error – two of the works here are amongst the most challenging in the orchestral repertoire; the concerto so well-known any performance has to be quite special. The bar for this concert was high.

Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is played much less often than one thinks. It is easy to see why Walt Disney used works like this and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in Fantasia; these are pieces of music that liberate the old world into something transformative, escapist, and distinctly modern – and above all vivid, imagistic, and cinematic. The Dukas, in particular, is so gloriously orchestrated to tell us the narrative of Goethe’s fantasy we don’t really need visuals to see what is going on; it is all in the music. Played by a great orchestra, and guided by a great conductor, hearing this work should be one of the most enjoyable experiences in the concert hall. However, like many orchestral showpieces it can easily pan out into glibness or an arrogance of virtuosity.

So much of the work in this piece is characterised by the woodwind – the broom is first brought to life by the bassoon (almost sounding like hiccups) and when the apprentice breaks it in half we get the addition of a bass clarinet. The maelstrom of the flood brings the orchestra swirling in – the magnificent glockenspiel (so formidably written for the part), the quicksilver strings (in contrast to the shimmering, ghostly opening). This should be a Herculean orchestral battle – a sonic struggle of the hopelessly overwhelmed buckets fighting back against the torrential deluge from the tub. Order and punishment is then restored through the trumpet of the sorcerer. Petrenko had the RPO playing in a magnificent chaos – everything in place, even if the illusion was of symphonic anarchy and a world gone awry. There was a freedom here that let the performance flow with thrilling energy. No matter how clearly the music spoke for itself I couldn’t help but watch this performance as a piece of brilliantly animated cinema and I was by no means anywhere near the only person to view it this way.

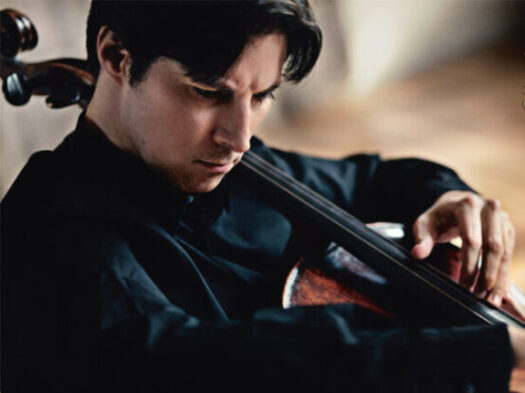

Although I largely prefer Elgar’s Violin Concerto, the one for cello has often worked better for me with male soloists. One of the most searing performances I have ever come across is with Yo-Yo Ma and (of all conductors) Claudio Abbado given with the London Symphony Orchestra in their very first Barbican concert. I can’t say that Daniel Müller-Schott was in quite the same league; I worried, for example, that his nobilmente ff chord in the first bar just lacked the power to carry much sound around the Royal Festival Hall.

This actually wouldn’t prove to be the case, largely because he overcompensated with some heavy vibrato and his instrument proved to have a very rich and resonant sound indeed. Sometimes, however, his bowing felt just a little loose sliding uncomfortably over the string so the note sounded hazy, too. But largely, this was a superb performance – especially when the soloist was working with the orchestra. The patience he took playing with the clarinet and horn early in the first movement, for example, showed he understood the balance needed between the pianissimo and the tension he applied to his own bowing. When he needed to play in unison with the cellos he looked at them and the effect was magical precision. Müller-Schott – unlike some recent cellists I have heard in this concerto – was prepared to see this as a collaboration in a work where the cellist often sets the pace – he does, after all, control the opening tempo which the conductor then follows.

It felt right that he took Elgar’s sostenuto marking as written just before the long scale ascent to top E – although arguably it was better done in the repeat of it in the fourth movement just before the magnificently played three and a half octave descent into Elgarian harrow. The finale was where Müller-Schott was most impressively virtuosic in a concerto which often underplays it – triplet passagework across the strings, precision perfect pizzicato and semiquaver flourishes. The emotional core of the movement was often established on the weight of his finger vibrating heavily – but it worked.

What had opened as an underpowered performance closed as one which had been driven by intensity, and not a little forcefulness. What it lacked was saccharine sweetness – and for that one should be thankful; this is often the worst outcome in performances of this concerto. The encore was the Gigue from Bach’s G minor Suite – played with freshness and clarity and without any of the weight of the Elgar.

The final work on the program was Tchaikovsky’s great Manfred Symphony. The discography of this work is dominated by performances from London’s orchestras – the RPO having made an excellent recording itself with the Japanese conductor Kazuhiro Koizumi in 1992. If Vasily Petrenko’s performance was by no means a disappointment it was certainly a controversial, and in many respects unconventional one.

Manfred is Tchaikovsky at his most extreme. Its length makes it unwieldy; it is structurally problematic. The score is a nightmare – not only is it difficult to play, but Tchaikovsky’s use of accents, bow markings and tempo instructions is so voluminous few performances are entirely everything the composer wanted. In other words, the chances of the work coming across as messy are high.

What Petrenko did manage to get was quite superb playing from the RPO. Ideally, the violins could have sounded weightier – certainly not a complaint one could have made of the cellos and basses here as they rumbled and thundered through Tchaikovsky’s Byronian inferno.

Although the general tempo for the first movement came in relatively quickly, some sections were notably slower than others and it sometimes distorted the picture we got of the music. I wondered, for example, whether the beginning of the first movement coda (effectively beginning at the Un poco più mosso) was really ♩ = 76 (it sounded slower), and whether the first and second violins were quite at fff compared to the ffff for the violas, cellos, and basses; effectively the sheer weight of the violins became dominant. On the other hand, the change to ♩ = 84 at Più animato felt swifter. What is unquestionably true about Petrenko’s handling of the coda is that he brought a greater sense of organic contrast to it than almost any conductor I have heard do it in concert.

Similarly, I wondered why Petrenko in the Andante lavished so much detail on the violins’ bowing, before the Forgetfulness motif (bars 220 – 223) but then didn’t do the same during the Più mosso section which immediately follows it when it has identical bowing – nor was he, for that matter even close to Tchaikovsky’s ♩ = 76.

There had, nevertheless, been much to admire. Beginning in dolefulness, Petrenko managed to get the RPO in the first movement to achieve marvellously graphic playing. Like a horde of wailing and howling demons, the woodwind and strings were often well done – and when you got 1/16th triplets in bars the effect could be chilling and full of terror, especially in the flutes and oboes. The first vision we got of Astarte was purely dramatic (an incredibly lugubrious descending scale on the double basses). Slow – although powerful – as the coda may have been, there had been no added timpani; none of the crashing tam-tam’s Russian conductors were so fond of throwing in at the end.

The Scherzo rarely causes problems, despite its length. A movement of symphonic contrast it’s brilliantly crafted and Petrenko understood the concept of ‘falling water’ which underscores it. The woodwind playing was outstanding, Tchaikovsky’s placing of higher semitones not always easy to spot. The down rushing chord passage, in the clarinet and horns, and which depicts Manfred’s invocation of the witch of the alps, appeared within a beautiful spray of harps and violins. When the harps appeared again in the Trio they were covered in mystery.

The Andante had been straightforward enough, although the music can be far from comfortable. Petrenko had the horns admonish cries of despair, just as the trumpets would during the movement’s main motif. The Allegro con fuco sometimes felt a little overwhelming and imposing. I am not sure Petrenko ever saw much of Berlioz’s Harold in Italy here – the exuberance and revel of the music was often lost.

The rather grander approach he took sometimes undermined the drama of the Witches’ Sabbath, for example. The trills in the strings, high woodwind, cymbals and tambourine which are its beginning lacked a compelling, visceral horror. The Lento section, however, was magnificent. Minims and semi-breves had beautiful weight and length, the p and mp were distinctive. The tone was as foreboding as it should be. The howl of rage that came from the brass had been full of dread as Manfred with his incantation forces the powers of Hell to do his bidding. The Fugato itself, where the spirit of Astarte appears, was terrific. One advantage of hearing Manfred in the Royal Festival Hall is that the organ is going to be spectacular – and it was.

Manfred’s annihilation had become complete and if the organ is in any sense a plea for him to reconcile with the church it was doomed to fail. Performances of this symphony rarely end in anything other than despair – it is just a question of how deep it goes. For Petrenko, the RPO’s double basses plummeted to a deep B, surrounded by fragments of the Dies Irae, and it was as dark as it could possibly be.

In many ways, quite a remarkable evening.

Marc Bridle