United States Various: Marc-André Hamelin (piano), Cleveland Orchestra / Daniel Robertson (conductor). Mandel Concert Hall at Severance Music Center, Cleveland, 1.12.2024. (Reviewed as a livestream on clevelandorchestra.com/adella). (MSJ)

United States Various: Marc-André Hamelin (piano), Cleveland Orchestra / Daniel Robertson (conductor). Mandel Concert Hall at Severance Music Center, Cleveland, 1.12.2024. (Reviewed as a livestream on clevelandorchestra.com/adella). (MSJ)

Copland – Suite from Appalachian Spring; Suite from The Tender Land

Gershwin – Rhapsody in Blue

Ellington – New World a-Comin’

While many US ensembles take the weekend off at Thanksgiving, the Cleveland Orchestra has long made it a practice to offer concerts. A time of thanks and remembrance, it is also a good time to salute one of the features here in the 1990s, when composer Peter Schickele used to lead classical comedy concerts featuring the music of his alter ego, PDQ Bach, always billed as ‘The Cleveland Orchestra’s Annual Thanksgiving Turkey’. Schickele passed away earlier this year, and is remembered fondly here and elsewhere.

This year’s feast was Americana, with both favorites and lesser-known gems warming up Severance Music Center while lake-effect snow blew fiercely. Central to the program was the original jazz band version of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, with the great Canadian pianist Marc-André Hamelin as soloist. Hamelin is known for his fabulous technique and wide-ranging repertoire. For instance, he was featured last year in a Tiny Desk concert on National Public Radio playing a set consisting of CPE Bach, William Bolcolm and a composition of his own that was written as a challenge for contestants in the Van Cliburn Competition. There seems to be nothing this man cannot play. Is Rhapsody in Blue any kind of challenge for him? Well, suffice it to say that Hamelin knows where the art is in music. It is not in the athleticism of the solo part, it’s in the life that can be found in those notes.

Gershwin’s delectably discursive rhapsody celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary this year, and it has become a common visitor to concert programs. A reader once accused me of not liking the piece because of a dismissive review I wrote of a bad performance. On the contrary, I adore it, but I have been jaded by second-rate pianists trying to impress with athletic velocity at Gershwin’s expense. No such qualms with Hamelin, who has nothing to prove on that front. His focus throughout was on finding the flavor of Gershwin’s intoxicating brew, letting its sheer invention motivate the movement from section to section.

The performance was happily of the original jazz band version including, for extra delight, a few bars that are often cut. This version is perkier and more incisive than Ferde Grofé’s later rearrangement for large orchestra, and it really should be played more often. It started off with Daniel McKelway enjoying the opening clarinet solo without milking it excessively. McKelway served as a thread throughout the piece, playing jazzy licks to counterpoint the piano solos, which Hamelin savored with sophisticated style. Daniel Robertson matched Hamelin’s poise, even finding a moment to surprise: in the crescendo leading up to the pause before the coda, he accelerated instead of slowing down, a detail of the manuscript score (downloadable from the International Music Score Library Project online) that is usually ignored, even by Gershwin himself in his piano roll recording.

As an effective counterpoise to the Gershwin, Duke Ellington’s New World a-Comin’ opened the second half of the concert. While it may not be as full of melodic hooks as the Gershwin (what else is?), the piece is a gem. Ellington would be pleased to see it making inroads in the classical establishment after all these years, verifying his famous dictum: ‘There’s only two kinds of music, good and bad’. This was an example of the former.

The performance featured the symphonic version arranged by Luther Henderson (and edited by Jeff Tyzik and John Nyerges). For the sake of argument, considering that the jazz band version of the Gershwin was used in this concert, there is an orchestration by Maurice Peress (which he recorded) based on one of Ellington’s original 1943 performances of the piece with his band at Carnegie Hall, but I don’t know if it has been published for use by others. At any rate, the fuller orchestration certainly matches Ellington’s ambition to have a symphonic outlay for the piece, and its lushness matches the textures that jazz composers were using twenty years after Rhapsody in Blue.

Hamelin displayed the same warmth and poise in this piece as in the Gershwin, bringing it to life in a manner that eludes most pianists. Although Ellington made an improvised solo cadenza in his original performance – and Sir Roland Hanna, the soloist in the above-mentioned Peress recording, took an even longer one – Hamelin did not, sensing that an aside by anyone but the composer would only weaken the work’s flow. Robertson and the orchestra made the instrumental contributions swing and glow.

The concert was bookended by two Copland suites, one from the ballet Appalachian Spring, the other from the opera The Tender Land. The latter was the concert closer, perhaps dictated by the stage management requirements of moving the piano on and off. The music is drawn from an unsuccessful opera that Copland wrote at the time he was being grilled by members of the US Congress during the height of McCarthyism. Copland, who had espoused an interest in communism in the pre-World War II era, hastily backtracked when put on the spot, nervous that his populist music of the 1930s and 1940s would be likened to Soviet ‘socialist realism’. Perhaps this scrutiny inhibited his composition process: although the music is beautiful and, on the surface, seems like typical Copland populism, the fact remains that it fails to register as trenchantly as the composer’s earlier works in this style. And while Copland’s sheer invention made the music for Appalachian Spring convincing, there is nothing in the music for The Tender Land to suggest any involvement with or knowledge of the actual Midwest. It also lacks the sensitive transition points that help the Appalachian Spring suite flow. This was a strong presentation by Robertson and the orchestra, but the music itself lacks that mysterious something which separates the great pieces from everything else.

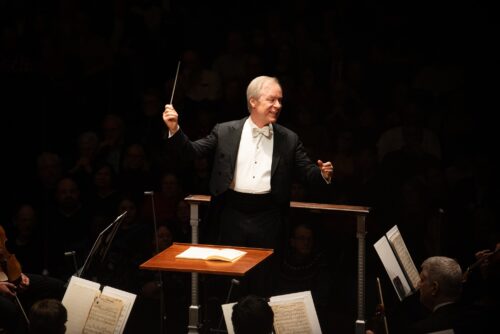

The Appalachian Spring suite could not be more different. From the iconic opening onwards, each new turn of phrase results in the discovery of unforgettable music abounding with melodic hooks. For such a familiar classical hit, the piece is pitted with dangers in performance. It requires great tenderness but can sag if that tenderness deteriorates into sentimentality. And while it is based on folk-tropes, it clearly remains the work of a modernist composer. Perhaps that is why David Robertson proved an ideal conductor for it. Robertson first became known as a protégé of the formidable French modernist Pierre Boulez, able to match his mentor in logic, clarity and lucidity.

Robertson achieves linear flow in a way that escaped Boulez, who seemed fixated on vertical harmony. The former is a master of sensitive transitions, allowing him to examine Copland’s music with great tenderness without ever falling into the trap of sentimentality. This sense of flow subtly kept the music pulsing. Without grandstanding nor overcautiously restraining, Robertson brought the music to life in a rare manner, letting the geniuses of the Cleveland Orchestra run with it, steering them through the transitions but allowing them room to flourish. Just before the end, the camera from this excellent livestream even caught for a second the tears streaming down Robertson’s face. It was the right response.

Mark Sebastian Jordan