United States R. Schumann, Mozart, Mendelssohn: Mao Fujita (piano), National Symphony Orchestra / Fabio Biondi (conductor). Concert Hall, Kennedy Center, Washington, 5.4.2025. (ES-S)

United States R. Schumann, Mozart, Mendelssohn: Mao Fujita (piano), National Symphony Orchestra / Fabio Biondi (conductor). Concert Hall, Kennedy Center, Washington, 5.4.2025. (ES-S)

R. Schumann – Julius Caesar Overture, Op.128

Mozart – Piano Concerto No.25 in C major, K.503

Mendelssohn – Symphony No.4 in A major, Op. 90, ‘Italian’

Over the past several decades, Fabio Biondi has certainly played a role in the development of historically informed performance, bringing together scholarly precision and a lively, instinctive musicianship. As founder and director of Europa Galante, he has infused Baroque and Classical repertoire with a Mediterranean brightness that sets his interpretations apart from more austere or academic approaches. Whether leading from the violin or the podium, he has brought his engagement with historical style – filtered through a flexibly expressive lens – to both period- and modern-instrument ensembles.

His subscription series with the National Symphony Orchestra at the Kennedy Center followed a typical overture–concerto–symphony format. The overture proved the weakest link of the evening. Robert Schumann’s Julius Caesar, rarely heard and for good reason, is arguably among his most rigid and underdeveloped orchestral works. Composed in the later years of his career, it reflects the increasingly constricted character of his late style – more severe in tone, less pliant in rhythm and texture. Intended as a bold, dramatic gesture in homage to Shakespeare, the score offers little of the psychological nuance or expressive fluidity found in Schumann’s earlier orchestral music. Instead, it plods with grim determination – heavy on martial rhetoric, light on structural or harmonic interest. Biondi and the NSO delivered it with earnest conviction, but the piece remained stubbornly opaque and unpersuasive.

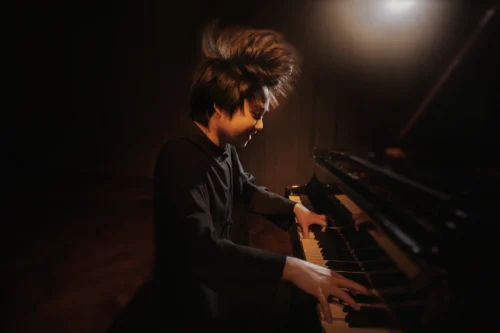

The atmosphere brightened the moment the young Japanese pianist Mao Fujita took the stage for Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.25 in C major, one of the composer’s most ambitious and architecturally expansive works. Making his debut in an NSO subscription series, Fujita delivered a performance of refinement and expressive intelligence, ably negotiating both the concerto’s heroic breadth and its more elusive, inward nuances. Modest in demeanor, playing with disarming simplicity and deep insight, yet clearly determined to make his voice heard, Fujita seemed the one who pulled forward an orchestra that at times floated just behind his expressive lead.

His very first entrance, emerging organically from Biondi’s ceremonial orchestral exposition, was remarkable: diaphanous and weightless, it set the tone for a reading that favored grace without losing anything in terms of structure. Sudden modulations and shadows were full of mystery. Notably, his transition out of the development was handled with a gradual intensification of touch rather than dynamic force, reasserting control without interrupting the musical line. The cadenza – Fujita’s own – was harmonically adventurous, texturally rich and flirtatiously Romantic in spirit without betraying the Classical poise of the work. The second movement, a restrained and contemplative Andante, offered an oasis of lyrical intimacy, and Fujita’s finely spun phrasing dovetailed with the woodwinds in a measured, luminous exchange.

The finale, a sonata-rondo, sparkled with rhythmic buoyancy and wit, its dance-like themes dispatched with elegance and flair. Fujita, who won the prestigious Clara Haskil Competition in 2017, has since proved to have a profound affinity for Mozart’s piano sonatas and concertos. He reminded us once again why he is considered a worthy inheritor of Clara Haskil’s legacy of transparency, depth and inner expressiveness.

If Mozart’s Concerto No.25 might be considered a transitional work between Classical and early Romantic, Mendelssohn’s ‘Italian’ Symphony, heard after the interval, was imbued – under Biondi’s attentive, detail-oriented direction – with a lingering Classical clarity.

Mendelssohn composed the work during a year-long sojourn in Italy, completing it in Berlin in 1833. The symphony traces a journey from sunlit exuberance to processional solemnity and ends in a spirited Southern dance, all within a Classical four-movement frame. With an expanded string section – which went from three double basses in Mozart to eight – Biondi drew vivid colors from the NSO, favoring clean articulation and flexible phrasing over sheer volume. At no point did one have the impression of a heavy touch.

The opening Allegro vivace had the right degree of underlying tension, its brightness edged with a sense of forward motion that evoked what Mendelssohn once described as ‘blue sky in A major’. The Andante con moto, inspired by a Roman religious procession, was solemn but not ponderous, with fine ensemble cohesion even in the softest textures. The third movement, Con moto moderato, had the elegance of a lightly stylized minuet, with horns and woodwinds floating in and out of the texture without dominating it. The final Saltarello was taken at an urgent but transparent tempo – fleeting and weightless – its quick-footed momentum shaped not by force but by precision. This was not Mendelssohn as high drama but as carefully etched vitality: Classical in balance, shaped by a Romantic sensibility and graced with the brightness and buoyancy the composer associated with Italy. Not a melodramatic opera set full of chiaroscuro, but a Corot-like canvas – lucid and sunlit.

Edward Sava-Segal