United Kingdom Glass, Akhnaten: Soloists, skills ensemble, Chorus and Orchestra of English National Opera / Karen Kamensek (conductor). London Coliseum, 29.3.2023. (CC)

United Kingdom Glass, Akhnaten: Soloists, skills ensemble, Chorus and Orchestra of English National Opera / Karen Kamensek (conductor). London Coliseum, 29.3.2023. (CC)

Production:

Director – Phelim McDermott

Set Designer – Tom Pye

Costume Designer – Kevin Pollard

Lighting Designer – Bruno Poet

Choreography – Sean Gandini

Cast:

Akhnaten – Anthony Roth Costanzo

Nefertiti – Chrystal E. Williams

Queen Tye –: Haegee Leee

Scribe – Zachary James

Aye – Jolyon Loyy

Horemhab – Benson Wilson

Daughters of Akhnaten – Ellie Neate (Bekhetaten); Isabelle Peters (Meretaten); Ella Taylor (Maketaten); Felicity Bucklandy (Ankhesenpaaten); Amy Holylandy (Neferneferuaten); Lauren Young (Sotopenre)

Gandini Juggling

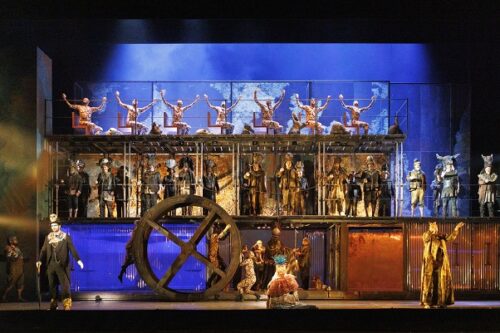

Back in 2016, Phelim McDermott’s production of Glass’s phenomenal opera Akhnaten was fresh and new (see my review, which goes into some detail about the background of the juggling aspect of the production, and also the spiritual/religious significance of Akhnaten’s monotheism). The production returned in 2019 and seeing it in 2023 just brings home the power of both Glass’s music and McDermott’s staging. I still feel a sigh of relief coming on when we approach the scene in which Glass looks back at Akhnaten’s time from the present. McDermott handles it sensitively (a far cry from the English National Opera production of this work in the 1980s).

The inclusion of juggling – identified from various Egyptian writings and artefacts – remains a fascinating element to this, and Improbable‘s contribution is faultless. The repeated motions of juggling do indeed seem to map onto those of Glass’s music rather well, and of course this can act as a sort of silent chorus reflecting events through their actions. Bruno Poet’s lighting is remarkable, not least in the final scene where Akhnaten is seen at the top of a staircase against an illuminated orange sun (‘Ra’, the only remaining God from the pantheon in Akhnaten’s reign).

Of the three figures that changes the course of history that Glass chose as operatic subjects, Akhnaten is the least well known (the others are Einstein for Einstein on the Beach and Gandhi for Satyagraha). Yet Glass places him in equivalent importance. He is fascinating – a hermaphrodite (stunningly reflected in this production and through Kevin Pollard’s costumes), it is only right he should be represented by the crystal-clear voice of a countertenor. Anthony Roth Costanzo has had great success with this role, starring in the Met recording – live from November 23, 2019 – with the present conductor, Karen Kamensek. Personally, I found the ENO orchestra darker still then their American counterparts in the opening, just as it should be, and absolutely equal to their Met colleagues, if not surpassing them, throughout.

Recently, Costanzo was made a Visiting Fellow at the University of Oxford for his work in interpreting ancient historical records to inform his performances of this opera, and for nurturing interest in Egyptology. That sort of devotion to a role is remarkable, and he does appear to be one with Akhnaten. He seems to be one with Glass’s requirements, too, including the slowed-down bodily movements one sees. He sings with perfect, blanched tone, and delivers incredible vocal strength at times. Dramatically, he projects the almost alien strangeness of the character of Akhnaten to perfection. It is unsettling, and so it should be.

Akhnaten’s wife, Nefertiti, is sung by Chrystal E. Williams, who exudes gravitas; the role of his mother, Queen Tye, benefits from the glistening soprano of Haegee Lee. Wonderful to see an ENO Harewood Artist among the main cast members: Benson Wilson plays the general and future Pharoah Horemhab with an earthy voice and real dramatic authority. Jolson Loy makes a fine ENO debut as Aye (Nefertiti’s father and advisor to the Pharoah), depicted as a sort of voodoo circus master (he sports a skull on his top hat).

Zachary James returns in the spoken role of the Scribe, delivering his lines authoritatively, leading into the chthonic percussion of the Funeral of Amenhotep III perfectly (and how brilliantly the chorus delivered its post-Orff Minimalism here). The division of the stage into sections, in one of which we have seen the body of Akhnaten’s father (Akhnaten was originally Amenhotep IV), is a brilliant use of space. James is no stranger to Glass, incidentally – he created the role of Abraham Lincoln in The Perfect American.

It is a measure of the expertise of vocal casting in this production that the Epilogue – the ghosts of Akhnaten, Nefertiti and Queen Tye (Costanza, Williams and Lee) – meshed so perfectly together. The six Daughters of Akhnaten, including two ENO Harewood Artists, Isabelle Peters and Amy Holyland, similarly worked together perfectly as a unit (Act III, Scene 1, ‘The Family’). Tenor Paul Curievici was a fine High Priest of Amon.

Karen Kamensek conducts with the authority she has attained through maximal exposure to this score – it is surely part of her core psychic make-up by now. She understands how Glass occasionally subverts the rhythms (towards the end of Amenhotep III’s funeral, for example), and the results are massively exciting. She understands the power, in this opera, of the simple ascending scale (and Glass’s simple inverted counterpoint against it), first encountered in ‘The Coronation of Akhnaten’ and later, of course heard in the opera’s remarkable Epilogue. The Orchestra of English National Opera responds in kind. This score requires both stamina in a physical sense, but also a stamina of concentration, and to my ears at least the tension dropped not one jot throughout.

ENO remains a national treasure, and the London Coliseum remains its home, at least for now. How wonderful to see every seat full, mid-run. ENO has also long been a requisite counterpoint to The Royal Opera, and its relationship with the operas of Philip Glass is one of its most remarkable achievements. This Akhnaten is absolutely unmissable.

Colin Clarke