Germany Berlin Festtage [4] – Wagner, Götterdämmerung: Soloists, Staatsopernchor Berlin (chorus director: Martin Wright), Staatskapelle Berlin / Thomas Guggeis (conductor). Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Berlin, 10.4.2023. (MB)

Germany Berlin Festtage [4] – Wagner, Götterdämmerung: Soloists, Staatsopernchor Berlin (chorus director: Martin Wright), Staatskapelle Berlin / Thomas Guggeis (conductor). Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Berlin, 10.4.2023. (MB)

Production:

Director, Designs – Dmitri Tcherniakov

Costumes – Elena Zaytseva

Lighting – Gleb Filshtinsky

Video – Alexey Polubpoyarinov

Dramaturgy – Tatiana Werestchagina, Christoph Lang

Cast:

Siegfried – Andreas Schager

Alberich – Jochen Schmeckenbecher

Hagen – Mika Kares

Brünnhilde – Anja Kampe

Gunther – Lauri Vasar

Gutrune – Mandy Fredrich

Waltraute – Violeta Urmana

Three Norns – Noa Beinart, Kristina Stanek, Anna Samuil

Woglinde – Evelin Novak

Wellgunde – Natalia Skrycka

Flosshilde – Anna Lapkovskaja

Erda (silent) – Anna Kissjudit

‘Alles was ist, endet.’ Erda’s words from Das Rheingold apply both to the rule of the gods and to Wagner’s depiction of that rule, its decline, and its fall. The Ring does strange things to one’s sense of time, time in any case a strange thing to experience. By the time one reaches Götterdämmerung, let alone its end, one both feels one has been through a good deal, to put it mildly, and yet also that it has only just begun. Partly, of course, that is or can be the work’s message too. Wagner counselled Liszt to mark well his poem, containing the beginning and end of a world, not, as sometimes has been said, the world. Those ‘watchers’, men and women (on which Wagner is very clear) ‘moved to the very depth of their being’, who, at least according to his stage directions, should observe Brünnhilde’s final acts and who implicitly remain with us to create a new world, would otherwise have no role. Nor, on one level, would performing and staging the work. Here we were again, though: the end of another Ring, one which had challenged and taught us much, moving us too, even if not always living up dramaturgically to the moments of its highest promise.

For, if much of Siegfried, especially its first two acts, had left me enthused and eager to find out what might happen next, Götterdämmerung sometimes suggested Dmitri Tcherniakov had lost his way, failing to follow up – or at least electing not to do so – on themes and threads which instead were left hanging. Wagner’s more uncomprehending critics might claim he did so too; we have no need to discuss them further here. The research centre in which the work – all of it, probably – takes place opened up questions of agency and control in which Tcherniakov seemed, at least in part, to have lost interest. If the Norns, whom we had seen throughout, filing away information, seemingly keeping matters in order, are now locked out of proceedings, what does that mean? I could speculate, perhaps fruitfully, yet the production largely seems to abdicate any responsibility it might have to tell, to explain, to suggest.

The Tarnhelm’s failure again to work, Siegfried looking and dressing like Siegfried, not Gunther, on Brünnhilde’s mountain, could have many potential explanations and implications, yet where were they here? If the world has been disenchanted – fair enough, returning to Adorno and Horkheimer, or indeed many others – where, and I am sorry to bang on about this, does that leave the objects of Wagner’s work (musical as well as verbal and scenic)? It is not always clear to me that that problem has been adequately considered, though I think it could be in a revised production building on what has gone before. Where steps had been taken in Siegfried to suggest Wagner lay beyond any of the characters in setting up the experimental basis for the production, here if anything we went backwards — and it did not, Dallas– or Die tote Stadt-style, seem all to have been a dream.

There are lovely and other telling touches. The return of Erda and ultimately the Wanderer (his cloth cap still somewhere between Chéreau’s Brechtian ‘watchers’ and Wagner’s own carefully curated portraiture) to pay tribute to the dead Siegfried is genuinely moving. Has this particular experiment concluded? In that respect we can, I think justly, draw our own conclusions, however inadequate. Siegfried’s earlier Don Draper-like sprawling on the sofa and a plethora of cigarettes tell their own story of toxic – literally so – masculinity. So too does the basketball court on which Siegfried meets his death. That Gutrune may be drugged too is interesting: perhaps an addict rather than a formal object of experimentation, but is that not in any case part of a broader societal experiment of death and disaster? (Her other treatment is decidedly unsympathetic to the point of misogyny: a pity.)

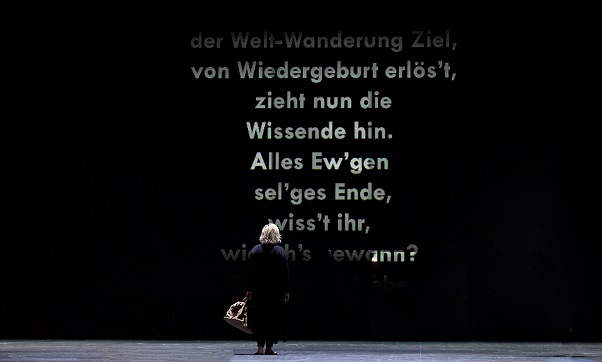

And what to make of the ending? I am tempted to say very little. To the text of Wagner’s rejected ‘Schopenhauer ending’ – he rejected it for sure dramatic reason – Brünnhilde approaches Erda, ultimately rejecting a paper bird such as Siegfried had rejected from the Woodbird. She pulls down the curtain, after it has become stuck. Making her own way with a clichéd bag in hand? Doubtless, yet could we, should we not expect more? It did not strike me as a deliberate drama of the underwhelming, a world failing to end, as in Frank Castorf’s Bayreuth Ring, rather a need to do something, almost anything. But perhaps, even probably, I am failing to understand. Tcherniakov’s Parsifal and, more controversially, his Tristan were tauter, more thought through. Is the lack the message? We begin to pursue ourselves, or our thoughts, in circles.

More understandably, Thomas Guggeis’s musical interpretation seemed to have tired somewhat. It was still an excellent show, a fine achievement for one at this stage of his career, which would put many others to shame; yet, a few orchestral fluffs (near-inevitable) aside, there were a few more cases where, not unlike the staging, the conductor did not always seem sure where next to turn. There was tremendous playing from the Staatskapelle Berlin led, at its best, by a keen sense of where the score was heading, but there were hesitations too. That, I have little doubt, will change with greater experience.

Andreas Schager’s Siegfried created the drama before him: tireless, cocksure, yet with a crucial degree of stunted development (Tcherniakov’s toy horse Grane another nice touch). He and Anja Kampe as Brünnhilde once again held the stage at least as well as anyone this century. Mika Kares added Hagen to Fasolt and Hunding, excelling once again in words, music, and gesture. Lauri Vasar (Gunther) and Mandy Fredrich (Gutrune) were not given the most promising hands in Tcherniakov’s conception, teetering on the edge of the merely silly, yet worked to gain our sympathy — and ultimately succeeded, a true sign of excellent artistry. The Norns and Rhinemaidens made fine contributions, though Violeta Urmana’s Waltraute did not make so consistently strong an impression as one might have expected.

It was, moreover, a joy to welcome back, however briefly, Jochen Schmeckenbecher’s thoughtful, detailed portrayal of Alberich. As so often, one’s thoughts returned to him, dead, alive, or somewhere in between. ‘Schläfst du, Hagen, mein Sohn?’ That near-liturgical question, so alluring to Boulez at work with Chéreau on the Centenary Ring, retains its irrational enticement. In lieu of a more conventional conclusion, that might do.

Mark Berry