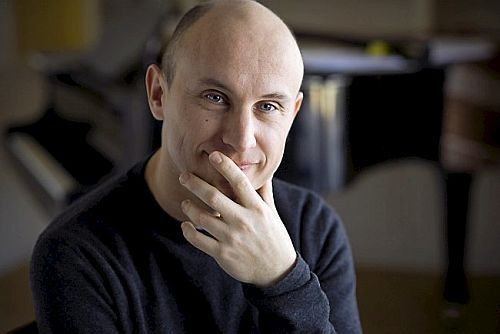

Interview with Pianist Nelson Goerner

Talking to 45 year-old Nelson Goerner is an illuminating experience. One gets the picture of an artist who has worked so painstakingly from his original Argentinian roots to build his craft and interpretative abilities up to the highest and most rigorous level, while at the same time thinking deeply about every facet of style and performance. The pianist has a clear virtuoso side and a very romantic one too, but I was impressed with just how classical much of his training and perspective is. While wanting to maintain his autonomy as an interpreter and an artist, Mr. Goerner pays great attention to the lessons put forth by the legendary pianists of the past, a number of whom he has played for and studied with. In March 2015, the pianist’s new Schumann disc was honoured as ‘Record of the Month’ by BBC Music Magazine. In 2013-14, he gave four recitals in the Artist Portrait series at Wigmore Hall, and his appearances in 2011 with Martha Argerich – at the Edinburgh and Verbier festivals – stand as testimony to their initial association many years ago. In this interview, Mr. Goerner reveals the important artists and influences in his past and how they have shaped his current perspectives, and he also talks about performing Beethoven – which happens to be his next recording project. He appeared recently in Vancouver, giving a recital of Bach, Mendelssohn and Beethoven for the Vancouver Chopin Society.

Geoffrey Newman: Every Argentinian artist seems to have a Martha Argerich experience tucked somewhere in their past. What is yours?

Nelson Goerner: My story starts when Martha came back to Argentina for the first time in 14 years in 1986. It was a very big event for Buenos Aires, and everyone had the highest expectations. She was the first piano legend that I had ever heard ‘live’, so you can imagine what it was like for me, 16 years old and a piano student at the time. And so she came and did a wonderful concert, unbelievably playing three concertos: the Beethoven 2nd, Liszt 1st, and Prokofiev 3rd. I attended both the concert and the rehearsal in the morning. The rehearsal was as amazing as the concert, but she played very differently. Some things I liked more in the rehearsal, some things more in the concert.

GN: Were you able to meet her at that time?

NG: You know, I never had the idea that I could meet her. However, she had been away for a long time, and she really wanted to hear some young Argentinian pianists. A meeting was arranged with young artists, but it turned out to be something quite different from what she intended. Many ‘society’ people showed up and others too who didn’t belong to ‘Argentine piano students’, and she was not at all happy. It turned out to be quite bad at first because Martha retreated to the kitchen of the flat where we were gathering – and didn’t want to come out! A couple of youngsters (myself included) were with her, and she told us how distressed she felt. So we started to have some conversation and, eventually, we pulled her out (literally!) from the kitchen. I was the first to play for her. I remember very clearly that I was preparing for the Liszt competition, so I had plenty of Liszt in my fingers. I played the 2nd Ballade, and then other people played. She was very complimentary to me, but I didn’t expect anything more. Yet just a few days later, it turned out that that Martha wanted to see me again; she was thinking of a scholarship for me to study in Europe. So that was totally unexpected news! Looking back, this meeting thirty years ago was the most fundamental thing in determining where I am today. Martha was the reason I first went to Europe (and live there today); it would have been extremely difficult for my parents to organize any of this.

Of course, with a person like Martha there are many followers and a lot of people who want to be close to her. For sure, a name like hers can open doors for a young artist. Yet I think I was always aware (and still am) that, if you want to do something, it has to be by yourself, on your own merit, not dependent on someone else’s reputation. I still remember feeling that it was very important that my career not be linked to hers.

GN: As I understand it, you then went to study on the scholarship at the University of Geneva with Maria Tipo, who Martha thought was a ‘sensational’ pianist.

NG: I asked Martha who she would recommend, and she told me that Maria Tipo would be wonderful for me. She also gave me a few names that I didn’t know. Maria Tipo’s name rang in my ear because she was very famous in Argentina. She had played a lot of concerts in Buenos Aires, but before my time. I also thought that, having been brought up in the Scaramuzza school, it might be an excellent continuation of my training to study with another Italian, albeit in a different branch of the Italian school. Continuing along the same path was very important: I knew that some of my skills were good, and I didn’t want to get confused.

GN: What was it like studying with Maria Tipo? Was she very ‘old school’?

NG: She was still very active in concertizing when I first met her; she’s actually turning 84 this year. I got to see her many times, and her concerts were truly an inspiration for me. I will never forget her amazing performances of the Scarlatti Sonatas, Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze, the Chopin Second Concerto and many works of Bach. As a teacher, she was an interesting combination of new school and old, but still possessed a natural authority. I remember she said that playing for her, I would have to be afraid. On the other hand, she really did have a lot of warmth and generosity and, a few years later, she did something quite incredible for me. I was still studying with her but had just won the Geneva Competition and was starting to give some concerts – not many, but some. She had an important concert date in Milan – in fact, it was the last concert of the subscription season – but instead of going ahead with it, she generously offered it to me, saying, ‘Well, I think it’s a good moment for you right now, otherwise you will have to wait 4 or 5 more years until they get to know you’. And she went to the concert to support me: she really cared for her students. Of course, she must have had a very good relationship with the concert organizer. I have no doubt that the years spent with her were absolutely essential to my musical development.

GN: How supportive were your parents as your opportunities began to blossom?

NG: I do not come from a musical family, I’m the only one. My parents always took the advice of my teachers, and they were very wise in doing so, because they didn’t want to push me to play in public when I wasn’t ready. In many ways, I am very fortunate for this.

GN: Were there other important pianists that figured in your early years?

NG: I actually played for Rosalyn Tureck a year before I met Martha. I remember it very vividly: it was the Bach Year and she came to Argentina and played the Goldberg Variations. It was heavenly; I will never forget the performance. She also did a recital in which she played both the piano and harpsichord, and a master class at the Buenos Aires Conservatoire, where I first met her and played a Prelude and Fugue for her. I still remember all the things she told me – she was a fascinating lady! She returned to Argentina two years later, and I played for her twice more –from the Bach Partitas that I was studying at that time. She wanted me to come and study with her in New York, saying that she could perhaps help in getting me a scholarship. But at that point, I already had accepted the other scholarship in Europe. Rosalyn did help me professionally later on.

GN: It is noteworthy that both Rosalyn Tureck and Maria Tipo went through long periods when their tremendous artistry was not fully appreciated.

NG: That sadly happens all the time, and there are many examples. The world we live in, with all the marketing and business, often takes us away from the music and pushes the unique talents of many artists to the side. Since I’m also teaching, I see how pernicious it is for young people; they think that successful careers can be made mainly through the ‘image’ they project. But we eventually appreciate what the true artists offer – consider Nelson Freire’s struggle. These pianists were so outstanding when they were young, and yet they have faced so many difficulties in their life and careers, and such long periods where nothing happened. Yet when something did start to happen, they still had something very important to say and, finally, we recognize their greatness.

GN: Are there still other pianists who have inspired you?

NG: I must mention Radu Lupu. He was one of the big inspirations in my life, and still is. He has lived in Switzerland for many years (as have I), and our acquaintance now goes back 20 years. We happened to meet by chance, and I had the good fortune of being able to play for him. Over time, I’ve had the great pleasure of working with him on the Beethoven concerti, the Liszt sonata, and many other things. I have always been in awe of this artist. His sound! His palette! The polyphony! He never pushes, he lets the music speak. It’s incredible, the degree of communication he has with the music.

GN: It is interesting that you made your EMI debut disc of Chopin just after Martha Argerich recorded the two Chopin concerti for the same company in 1995. I recall a reviewer saying of the latter’s recording (paraphrasing): ʻHere is the real Chopin, sensual, full of colour, finally freed from Beethovenʼ. Is that the way you see this composer?

NG: I know that some artists tend to think of Chopin as occupying a completely separate world of expression, and that you should not link him to any other composer. I do not favour this view. There is a great amount of structure in his music – think about his sonatas, for example. People often think only of his miniatures but, fortunately, opinions are now being revised. For a pianist, I think it is as important to grasp Chopin’s structure – then through the structure, the meaning – as it is in Beethoven. Possibly, even more so! Besides, I think that there is always a connection between composers in music history; no one lives in a separate world.

GN: Glancing through your repertoire, I note that you are one of the few pianists to play Alfredo Casella’s Piano Concerto. Is this a work that came to you through your Italian training?

NG: Yes, I still have that in my repertoire. I would say it’s more of a small concerto, but it’s called Scarlattiana by the composer, and he exploits many themes that come from wonderful Scarlatti sonatas. I had a lot of pleasure learning the work because Casella was a well-known figure in Italy and elsewhere for many years. Early on, there was a concert organizer who happened to ask me for that piece, and I was frantic because I had never even heard of it. I got the score and the recording, and I learned it. Maria Tipo strongly encouraged me. She said, ʻYes, you should do it. It’s a very good piece. Casella was my teacher, and I will help youʼ. So I originally worked on it with her.

GN: I also notice that you have started performing the later Beethoven sonatas, such as ‘Les Adieux’, and the ‘Hammerklavier’ in the past year or so. What do you think is the right approach to mastering these, and the latter in particular?

NG: Works like these are always a problem. We can only really understand them after we have lived through enough yet we can only master them technically after many years of practice. I think that one must start on them when young and attempt to play them in concert – since that is also part of your experience and some things are only revealed to you when you are on stage. If you start when you are 40, you are too late. I learned many of the great Beethoven sonatas when I was young, including the ‘Hammerklavier’. It was important to me to know how I felt with the piece. Was I a little bit in the piece or not at all? As an artist, that’s important to know. But then I dropped these works for many years.

Naturally, I now see the slow movement of the ‘Hammerklavier’ as the heart of the sonata. How slow should it be? The lines are very long, and to be able to sustain that, the tempo should not be too slow. Also, we have to keep in mind that the composer asks for ‘appassionato’ – passion doesn’t mean fast – but it still moves you a little bit forward with a degree of anticipation. At the same time, you need the stillness. I think you can convey the feeling of stillness without necessarily being too slow. Perhaps it is not a matter of tempo, but rather whether a spiritual meaning is there or not. I also think there must be warmth in the ‘Hammerklavier’. As is well known, the composer himself said, ʻMusic comes from the heart and should return to the heartʼ. Again, when you see indications in the slow movements such as ‘appassionato con molto sentimental’, are we going to play that without warmth? I don’t think so. There is also the feeling of struggle, and one should be able to convey that in the performance, but I should note that it’s all quite different from the earlier ‘Appassionata’ sonata. The closing fugue is of course a struggle in every sense because it’s calling on superhuman forces, not just the performer.

GN: What about the more romantic composers?

NG: Mendelssohn came relatively late to me, and I want to do more of him. I got started through the Fantasy in F# minor, and I think it is a truly wonderful work. Again, it goes back to my teachers. Maria Tipo said to me one day, ʻYou should play Mendelssohn. He’s a wonderful composer for the piano. You should look at the Fantasyʼ. I didn’t do it immediately, but then I started looking at it, and fell completely in love. And many years later, I found that Jorge Bolet also thought that it was a great piece, and tragically neglected. I certainly want to try the Songs without Words and the Variations sérieuses before long. I adore Schumann and Brahms too, but again, there is an important link that I will try to explain. If you play Bach well, then it always helps you to play Mendelssohn, Chopin, Schumann, Brahms, and even later composers well. For example, I don’t think of Schumann as the uniquely schizophrenic, or literary, genius that some people might suggest. Fundamentally, he and other romantic composers owed so much to the classics: think of the love that all these great masters had for Bach’s music. So, it’s more a continuity than a separate thing. Even Debussy has these roots; his music is much greater than the lovely wash of colour you might want to hear.

GN: Perhaps you are truly a ‘generalist’ when it comes to repertoire and performance?

NG: I have always been impressed by the kind of artist that has a large repertoire because I can feel this exposure in their playing. They have such a range of emotions, expression and experience, and it allows them to encompass more than others. Of course, this is not the only way of doing things, and there are wonderful examples of people who specialize only in certain repertoire. But I never wanted that for me – it’s too restrictive. I want all composers! When I was really young, I was so impressed by an interview with Claudio Arrau that I read. He was saying that, for him, being an interpreter is like being a chameleon. A pianist must be at ease with and speak many different languages, and adapt to any style. I still remember that.

Especially in our time, I feel that people like to put others in drawers, to classify them. I think the very definition of the term ‘artist’ means a person who cannot be fully classified or labeled. Take a great artist like Rosalyn Tureck: she devoted herself only later in life to Bach. She played Liszt, Brahms and much else before. In the last concert I heard, she played not only Bach but also the Brahms Handel Variations, Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words and the Bach-Busoni Chaconne. The Chaconne was unbelievable: I didn’t expect it – so austere when playing the Goldberg, then pushing into the Bach-Busoni. Again, that’s a wonderful example that artists should not be put into boxes.

GN: It is well known that Martha Argerich now refuses to perform solo because she apparently feels too alone on stage. I’ve heard other distinguished pianists say somewhat the same thing, that they prefer performing concertos because the orchestra seemingly protects them. What is your take on this?

NG: It is true that with musicians on stage with you the experience is quite different. Sometimes the orchestra can be more supportive, sometimes less, but either way you are not lonely. And when things go well with an orchestra, and you have a good concerto performance, then it’s so rewarding because of the feeling that you have shared something. It’s an amplification of the chamber music experience, that sort of thing. In a solo recital, you do have to rely only on yourself, and it’s much more demanding – but I love that. You can play more in the inspiration of the moment, and do exactly what you want. I actually think there are only a few concertos that can reveal the true essence of an artist as a solo performer.

GN: You appear to achieve remarkable concentration when you play, always wanting to establish a completely worked out emotional equilibrium within yourself to go with the work’s technical demands. Is that something that you are conscious of?

NG: The continuity of the narrative, I would say, is one of the big challenges. That’s in the mind when I start. I try to forge that feeling. I think that from the outset it’s important to try to play through any piece, however imperfectly, as whole. That’s the thing I’m the most aware of – grasping the piece as a whole. Then I start to zoom in on the details, but not the contrary. Once you can penetrate the work’s overall structure and feeling, then the individual details can become significant.

Geoffrey Newman

I am indebted to Kelly Bao for recording and transcriptional assistance.

Previously published in a slightly modified form on http://www.vanclassicalmusic.com