United Kingdom Berg, Lulu: Soloists, Orchestra of the English National Opera / Mark Wigglesworth (conductor). London Coliseum, London, 9.11.2016. (MB)

United Kingdom Berg, Lulu: Soloists, Orchestra of the English National Opera / Mark Wigglesworth (conductor). London Coliseum, London, 9.11.2016. (MB)

(sung in English)

Cast:

Lulu – Brenda Rae

Countess Geschwitz – Sarah Connolly

Dresser, Schoolboy Waiter – Clare Presland

Painter, Second Client – Michael Colvin

Dr Schön, Jack the Ripper – James Morris

Alwa – Nicky Spence

Schigolch – Willard White

Animal Tamer, Athlete – David Soar

Prince, Manservant, Marquis – Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts

Theatre Director, Banker – Graeme Danby

Fifteen-year old girl – Sarah Labiner

Girl’s Mother – Rebecca de Pont Davies

Artist – Sarah Champion

Journalist – Geoffrey Dolton

Dr Goll, Police Commissioner, First Client – Rolf Higgins

Servant – Paul Sheehan

Solo performers – Joanna Dudley, Andrea Fabi

Production:

William Kentridge (director)

Luc de Wit (associate director)

Sabine Theunissen (set designs)

Greta Goiris (costumes)

Urs Schönebaum (lighting)

Catherine Meyburgh, Kim Gunning (video)

ENO’s new Lulu proved another triumph for the company: just what ENO should be doing; just, indeed, what ENO is for. One might, I suppose, quibble, whether ENO needed a new production; Richard Jones’s excellent staging might well have received another outing. (It should certainly have been staged more regularly than it was, but that, I suspect is more a comment on opera audiences than on artistic design.) But ENO did not mount this by itself; it performed us ‘citizens of the world’ a signal service by granting us the opportunity to see this much-discussed William Kentridge production, already seen in New York and Amsterdam. To say we should only have one, is akin to saying that because we have heard Daniel Barenboim play Beethoven, we have no need to hear Maurizio Pollini. It is the language of enemies of art, of accountancy; worse still, it is the language of those journalists determined never to miss an opportunity to find fault.

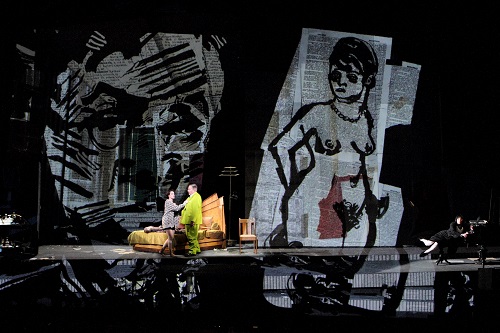

I shall admit to having been puzzled by some of the discussion I overheard. More than once I heard people complaining about there having been too much going on, even ‘sensory overload’. Have such people, I wonder, ever seen a Stefan Herheim production? More to the point, did they not think of how visual layering, the interaction between layers, between the visual and the aural, might actually be the point, a point very much in keeping with the work? What I saw was actually a relatively conventional, but highly theatrical telling of the story, enhanced, questioned, developed by an extension of its painterly imagery both in expressionistic drawings and film – an exhibition of Kentridge’s art may be seen presently at Whitechapel – and in the alluring yet sometimes ironic commentary, still very much in allusive ‘period’ style, by the silent artists, Joanna Dudley and Andrea Fabi. It was not remotely too much; indeed, like Berg’s score, it left me wanting more. This blackest of comedies gained in darkness – this was the night following the US election, something readily observable on almost every face in the house – and in sophistication of comedic response. I began to think of Berg’s musico-dramatic roots in Mozart and Wagner, in particular, and also of what he had in common with Strauss, another heir to that exalted pair, yet one far too little thought of has having much in common with the more overtly ‘progressive’, yet perhaps equally ‘nostalgic’, Berg.

Mark Wigglesworth’s conducting of the score, superlatively played by the ENO Orchestra was, of course, crucial in that respect. As Boulez, at work on the three-act premiere, once observed, ‘It is not so much the use of symmetry as the exploiting of multiple musical forms that is one of the most complex and attractive features’ of the music. Rather it in the confrontation between what Boulez broadly considered to be characteristic Mozartian number opera and the continuous – to which, I might add, increasingly symphonic – forms of Wagner that Lulu, in a different, or at least more complicated, less overt, way than Wozzeck will best find its performative voice. For Boulez, ‘The great advance from Wozzeck to Lulu lies in the fact that, although the scenes are still separated by interludes, there is now no “passage” between them.’ He found himself, unsurprisingly, especially attracted by the ‘fusion between continuity and formal separateness’. That, I think, was very much what we heard, and perhaps also what we saw, or at least what was suggested by what we saw, here. An especially fine woodwind section could not help but bring Mozart to mind: not just the Mozart of Così fan tutte but the composer of the wind serenades too. It was not for nothing that, in one of his final recordings, Boulez returned to Berg’s Chamber Concerto, coupling it with the Gran partita, KV 361. Melodies, harmonies, audibly generated before our ears by Berg’s endlessly fascinating compositional processes, and yet audibly as ‘free’ as they were ‘determined’, tantalised, instructed, informed, criticised, rather as the drawings, films, words, actions did before our eyes. This was no mere mirroring; it was mutual enhancement and elucidation, a new path through the Bergian labyrinth.

An excellent cast was necessary too, of course, and an excellent cast we had. Brenda Rae, who so greatly impressed me in the Bavarian State Opera’s Schweigsame Frau – now there is an interesting Strauss-Berg comparison to consider – shone at least as brightly as Lulu. The canvas on which we more or less uneasily project our fantasies of Lulu was no more empty than the changing visual decoration of the set, but, amidst, or perhaps beneath, the despatch of the coloratura and the seduction of the more conventional melodic line, there was a fine balance struck between nihilism and defiant character. Sarah Connolly’s Geschwitz certainly had the latter in spades; if I have seen and heard a stronger, more compassionate performance from her, I cannot recall it (which seems unlikely). If James Morris’s Dr Schön was at times a little stiff, there was certainly authority to be felt there, and his way with the words was especially admirable. Nicky Spence’s Alva struck another fine balance, in this case between the ardent and the cowardly; again, an admirable way with words and music projected ambiguity without easy, or perhaps any, answers. Willard White’s Schigolch was less caricatured, less repellent than one often experiences; such ambiguity was also decidedly a gain. There were no weak links, and a host of splendid character performances, artists such as Michael Colvin and Sarah Labiner particularly catching my ear. At least as impressive, though, was the ensemble work. In the Paris Scene, one might almost have thought this a crack new music ensemble, such was the clarity and confidence with which the lines were projected and with which they were interacted. It might almost have been a rehearsal for, or a response to, Strauss’s homage to his adored Così in Capriccio.

Mark Berry