United Kingdom J.S. Bach, St John’s Passion: Choir (Simon Halsey, chorus master) and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment / Sir Simon Rattle (conductor). Royal Festival Hall, London, 2.4.2019. (CSa)

United Kingdom J.S. Bach, St John’s Passion: Choir (Simon Halsey, chorus master) and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment / Sir Simon Rattle (conductor). Royal Festival Hall, London, 2.4.2019. (CSa)

in QAE’s St John Passion (c) Tristram Kenton

Mark Padmore – Evangelist

Roderick Williams – Christus

Camilla Tilling – soprano

Christine Rice – mezzo-soprano

Andrew Staples – tenor

Georg Nigl – baritone

Director – Peter Sellars

Assistant director – Hans-Georg Lenhardt

Lighting designer – Ben Zamora

Production stage manager – Betsy Ayer

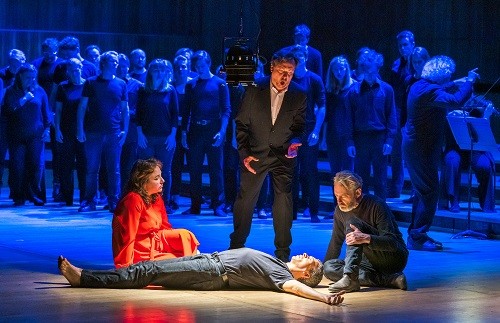

Compelling, powerful and steeped in emotion, Peter Sellars’s eagerly awaited London staging of J. S. Bach’s St John Passion by the Choir and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and a group of stellar soloists under Sir Simon Rattle, broke new ground for many ticket holders.

Those already acquainted with the US theatre director’s previous work, such as his visualisation of the St Matthew Passion in Berlin in 2001, or his famous 1996 Glyndebourne production of Handel’s Theodora, will have found themselves in more familiar territory. Sellars’s special gift is to animate the music and text of these richly dramatic eighteenth-century masterpieces, not, as Simon Rattle puts it, ‘by making theatre, but by making music visible’ on the stage. The use of expressive gestures, ritual movement and interaction between performers, coupled with subtle and dramatic shifts in lighting, are not employed simply to drive the narrative. They are also intended to liberate the vast and powerful range of emotion within these works from the shackles of traditional and more static modes of presentation, in order to create a direct empathy between the audience and the music.

In this respect, Sellars is undoubtedly inspired and influenced by the work of the great American contemporary video artist Bill Viola, with whom he previously collaborated. In his 2001 work The Quintet of the Astonished, for instance, Viola sought to replicate characters standing at the foot of the cross from Hieronymus Bosch’s painting Christ Mocked by filming actors grouped, dressed and lit in the way depicted by the artist on the original canvas. Viola then stretched out in slow motion what the old master could not paint – the group’s changing facial and physical expressions, ranging from joy and sorrow to anger and fear. Like Viola in his video works, Sellars in this production explores the themes of visual transcendence and emotional transformation; and, like Viola, he does so in the same painterly way.

There was an air of eager anticipation as the 30 musicians of the OAE, playing baroque instruments (or replicas) dating from the 1720s, clustered tightly together in the righthand corner of the Royal Festival Hall stage. This afforded a large space for the superb young choir, clad in black, to lie twisting on their backs, crawl, run across the stage, or gather in groups, every facial expression or gesture a direct physical response to the text and to Bach’s sinuous counterpoint.

The main responsibility for recounting St John’s dramatic story falls of course to the tenor Evangelist, on this occasion, the peerless Mark Padmore, whose clarity, sensitivity and sheer vocal grace in this role are unsurpassed. From the heart-rending moment of his first entry, his arms gently resting on the shoulders of Jesus (a commanding Roderick Williams) and Peter/Pilate (the magnificent Georg Nigl), we knew that his was not the customary detached narrator, but a sentient witness, intimately connected to the unfolding drama of Christ’s suffering and death. In a sustained 100 minutes of singing, Padmore displayed an astonishing variation of style and vocal technique. His tender ‘weinete bitterlich’ (‘wept bitterly’) as he recounted Peter’s repeated denials, and his outraged ‘Und gaben ihm Backenstreiche’ (‘And they smote Him with their hands’) are just two small fragments of an integrated performance which will live in the memory.

The only prop in this production was a hanging brass lamp. It was effectively used to interrogate Christ, but also served to bathe his face in a dazzling chiaroscuro glow. He was bound with his hands behind his back, blindfolded and on his knees while questioned by Pilate. At one point, Christ collapsed as an angry chorus, faces distorted by hatred, cry out ‘kreuzige’ (‘crucify’). These are not the easiest positions from which to sing, yet Williams’s versatile baritone ably projected Christ’s human vulnerability and his unassailable divinity, even his final whispered ‘Es ist vollbracht’ (‘It is finished’).

Georg Nigl (replacing Christian Gerhaher) gave us a dark-suited and strikingly contemporary Pilate, a kindly yet weak political placeman, whose question to Jesus ‘was ist Wahrheit’? (‘what is truth?’) sought to abrogate moral responsibility for his actions which, in the current climate, is all too familiar.

The singers in supporting roles were all of the highest quality. Tenor Andrew Staples sang throughout with brilliant intensity, ferociously spitting out the jagged rhythms of ‘Ach, mein Sinn’ (‘Oh my soul’). Christine Rice, a rich soft-grained mezzo-soprano, provided the only flash of colour in a scarlet gown, and poured out her grief-stricken arias over Christ’s crucified body as if her heart was truly broken, while soprano Camilla Tilling’s more restrained grief was conveyed with rare purity.

Presiding over, or rather, participating within this heavenly ensemble of musicians and singers was Sir Simon Rattle. Moving inconspicuously between his rostrum and the singers, he gently drew out and wove together the manifold threads of Bach’s rich tapestry, thereby helping to retell a familiar story with power and passion.

Chris Sallon

For more about the OAE click here.