Germany Puccini, Turandot: Soloists, Children’s Chorus (chorus master: Christian Lindhorst), Chorus (chorus master: Jeremy Bines), and Orchestra of the Deutsche Oper Berlin / Claude Schnitzler (conductor), Deutsche Oper, Berlin, 10.10.2019. (MB)

Germany Puccini, Turandot: Soloists, Children’s Chorus (chorus master: Christian Lindhorst), Chorus (chorus master: Jeremy Bines), and Orchestra of the Deutsche Oper Berlin / Claude Schnitzler (conductor), Deutsche Oper, Berlin, 10.10.2019. (MB)

Production:

Director – Lorenzo Fioroni

Revival Director – Philine Tiezel

Set designs and Video – Paul Zoller

Costumes – Katharina Gault

Cast:

Turandot – Elisabeth Teige

Altoum – Peter Maus

Calaf – Ragaà Eldin

Liù – Meechot Marrero

Timur – Byung Gil Kim

Ping – Samuel Dale Johnson

Pang – Michael Kim

Pong – Ya-Chung Huang

Mandarin – Patrick Guetti

Prince of Persia – Olli Rantaseppä (voice), Spyridon Markopoulos (stage)

Two Girls – Alexandra Hutton, Anna Buslidze

Having seen and thought well of Lorenzo Fioroni’s Deutsche Oper production of Turandot five years ago, I was keen once more to make its acquaintance. It did not disappoint, sadly remaining the only interesting staging I have seen, even though what I took from it this time was somewhat different this time around: whether from difference in emphasis onstage or in my reception I am not entirely sure.

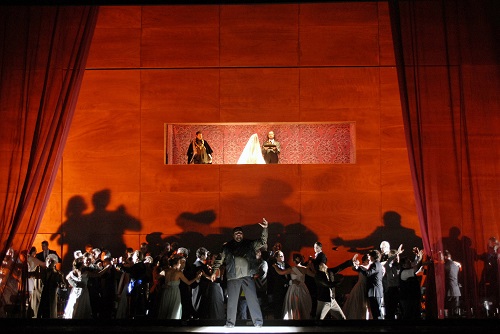

The setting is a relatively modern fascist state: perhaps 1970s, on the basis of costumes and flocked wallpaper, though I am not sure it especially matters beyond not being a regime of Puccini’s own time. (That would open up interesting possibilities for dealing with orientalism and downright racism, yet must await another day.) The people, who had never reminded me so strongly before of those in Boris Godunov, are kept in check by police brutality; quite who is running the show remains unclear, though, the Emperor clearly old and frail, and not alone in that in what seems externally to be a gerontocracy in desperate need of renewal. Why one woman in the crowd refuses to turn and bow to him is again never explained: is she deranged, a dissident, or both? She is eventually beaten into submission. Lack of explanation, though, enables one to draw connections as one will: of whom, or what, is she a harbinger? Liù in heroic defiance? Calaf in foolhardiness? Turandot in a hysteria that here strongly characterises both setting and action? We see Turandot desperately trying to keep things together both before and during the riddles. And she too must obey something higher, an initial refusal to concede following defeat met with police on either side of the stage barring her way.

Marriage of terror and hysteria is the overriding impression, indeed the true marriage, of which that of Calaf and Turandot will be but a reflection. It may and should be understood both politically and psychoanalytically. We see it in the video images of children unable to sleep prior to ‘Nessun dorma’; we see it in the crowd; we see it in the deeds of individuals. We see it also in the falling scenery after the interval (between the two scenes of the second act): the cruelty of a metal frame a metaphor for society and emotions alike. Liù remains hanging from a noose, a warning sign to those who might actually attempt to tell, let alone live, the truth: for her presence, at least that fashion, is also a lie: she was not hanged, but stabbed by the knife she grabbed and turned on herself. The repellent nature of Calaf’s victory is underscored by his final deed: moving to embrace his father, who had been wandering aimlessly before sinking in depression, only to stab him and, quite without emotion, return to his bride. A theatre of cruelty indeed.

Not that the commedia dell’arte is neglected, far from it, whatever the problematical nature of Puccini’s injection of (too much?) psychological realism into the scenario. (Perhaps the problem lies more with unsatisfactory performance traditions; a baleful operatic culture that too often damns Puccini’s operas with box-office-driven productions in mind has much to answer for.) Whatever the truth of that, the pantomimes performed by Ping, Pong, and Pang fascinate, enlivening yet ultimately disconcerting in their mockery. They anticipate, imitate, repeat endless rituals of hope and death that lie at the heart of this strange yet all too familiar society. Are they tellers of potentially liberating truths, in which a Turandot in travesty may gently be mocked? Ultimately not, it seems. Not only are they prisoners too; they, Ping in particular, participate with relish in the capture and torture of Liù. Perhaps they are not to blame; how could they act otherwise? (As we know, they would rather return to the country.) They offer a way of seeing ourselves in all our contradictions, as well as the other characters onstage. Rightly, they fail to live up to our delusional expectations.

Both the chorus and orchestra of the Deutsche Oper were on fine form, clearly relishing the cruel yet often playful drama of Puccini’s score. Claude Schnitzler led his forces well. If his direction sometimes seemed a little too hard-driven to begin with, only to relax a little too much in response, that should not be exaggerated. Harmonies that might have come from Schoenberg or Debussy were just as much the thing as Stravinskian rhythm. Puccini’s Italian heart continued to beat below, however sadistic its dictates. Elisabeth Teige and Ragàa Eldin both took a little time to settle into their roles as Turandot and Calaf. The former greatly benefited from relative taming of her vibrato, proceeding to offer a performance of considerable verbal and musical acuity. Once he had found his balance with the orchestra, Eldin likewise won his laurels, though he might have sung ‘Nessun dorma’ a little less as a stand-alone aria. The tragic tenderness of Liù’s death did great credit to Meechot Marrero, sadistic knife cuts from her torturer – onstage, that is, as opposed to the composer – rendering it close to unwatchable. From the rest of the cast, Samuel Dale Johnson’s quicksilver Ping made one especially keen to see and hear more, but his companions, Michael Kim and Ya-Chung Huang impressed too, as did Byung Gil Kim’s sonorous Timur. This was a strong company evening, then, that did credit both to the repertory system and to this ultimately bizarre and repellent opera.

Mark Berry