United States Wagner, Tristan und Isolde: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, New York / James Levine (conductor). Performance of 11.12.1999 reviewed as a Nightly Met Opera Stream on 13.7.2020. (JPr)

United States Wagner, Tristan und Isolde: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, New York / James Levine (conductor). Performance of 11.12.1999 reviewed as a Nightly Met Opera Stream on 13.7.2020. (JPr)

Production:

Production – Dieter Dorn

Designer – Jürgen Rose

Lighting designer – Max Keller

TV Director – Brian Large

Cast:

Tristan – Ben Heppner

Isolde – Jane Eaglen

Kurwenal – Hans-Joachim Ketelsen

Brangäne – Katarina Dalayman

King Marke – René Pape

Melot – Brian Davis

Sailor’s Voice – Anthony Dean Griffey

Shepherd – Mark Schowalter

Steersman – James Courtney

This was a Viewers’ Choice Nightly Met Opera Stream, though – without any exhaustive look – I don’t know how it was voted for. Other ‘research’ suggests it was reasonably well received at the time but despite having some good moments it was – by far – the least satisfactory of the recent ‘down memory lane’ opera productions I have watched during lockdown in the UK. (Unfortunately, the return of ‘live’ theatre – in all its forms – still seems a long way off here with all the ‘professors’ gazing into their crystal balls and prophesising huge second wave ‘best scenario’ death figures.)

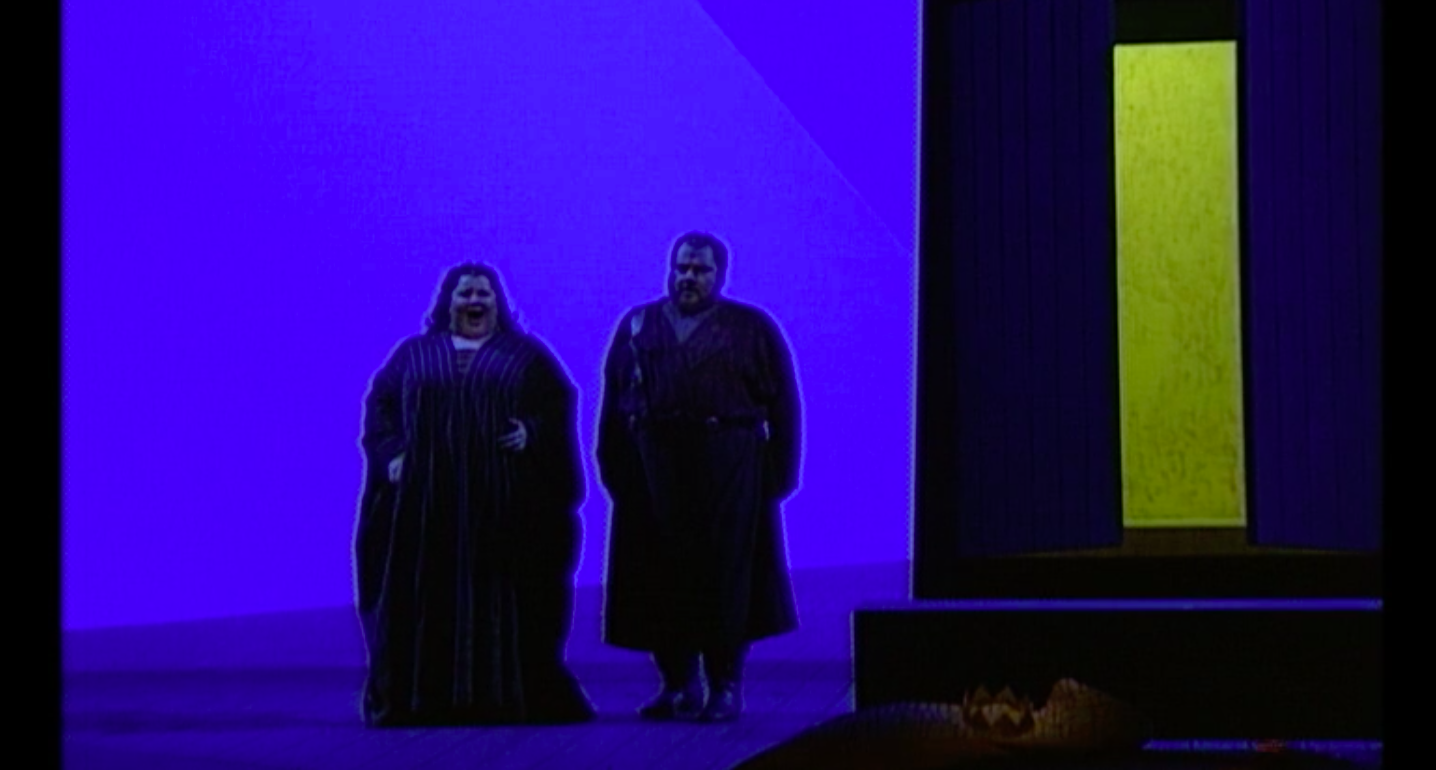

Dieter Dorn made his Met debut with this new Tristan und Isolde and it was not the type of production we are familiar with there. The staging was minimalistic, abstract, and symbolic and so there was no ship looking like a ship nor castles looking like castles. There was more than a hint of the militarism of feudal Japan from some topknots and Jürgen Rose’s costumes, and the three acts were confined within a trapezoidal-like tent – that suggested the sails of Tristan’s ship – that seemed to come to a point at the back of the stage. This was seen to its best advantage when Jane Eaglen’s Isolde returned late in Act III and processed slowly down – after Kurwenal describes how she ‘springs to shore’! – towards Tristan centre stage at the front. The wooden(?) flooring had trapdoors that allowed people and objects to appear and disappear through them, including Brangäne, as well as, King Marke and his men near the end of the opera. There was some typical Regietheater nonsense (also in Act III) with a toy castle and figures of jousting knights but otherwise the first two acts often just had a central monolith-like structure, perhaps as the mast for Act I and a castle turret in Act II?

Usually what we saw – mindful of the relative immobility of the two leading singers – was an elaborate semi-staging with all the singers rarely being more than a few feet from an eternal flame at the front of the stage; or more likely, the prompter? There was little need for Kurwenal and Brangäne to pull Tristan and Isolde apart as the best they did until a first chaste kiss in Act III was a merest brush of their fingers.

With all the attention clearly given to the singing, and not the singers as actors, it was left to Max Keller’s lighting – bright white, grey, yellow, blue, and red (for passion, I guess?) – to create what atmosphere there was and it mirrored the changes in the opera’s emotional temperature. Yellow seemed to be associated with King Marke and blue reflected some of Tristan and Isolde’s self-absorbed Act II ruminations on ‘blessed nearness, hateful distance’ (reminding me of ‘social distancing’!), as well as, the shame of the day and the ecstasy of the night. During the second act love duet, ‘O sink hernieder’ we just had Isolde and Tristan (Ben Heppner) sitting on a bench and their voices sounding somewhat disembodied as stark silhouettes against a blue supernal background. At this point – as sometimes elsewhere – TV director Brian Large clearly interpolated additionally filmed closeups of the two singers.

As Iain Burnside’s The View form the Villa wanted us to understand (review click here), there is considerably more extra-musical baggage to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde than possibly any of his other operas. Burnside concentrates on how Wagner was inspired by his infatuation with another married woman, Mathilde Wesendonck. It gets more intriguing when we consider how shortly before the opera’s premiere in July 1865, Cosima von Bülow, had given birth to Wagner’s daughter Isolde(!). That would have been okay had Cosima – who Wagner would later marry – not been the wife of Hans von Bülow at that time. He was one of Wagner’s disciples and the conductor of that first performance of Tristan! The mythical opera’s plot has the faithful knight, Tristan, betray his loyalty to King Marke – his surrogate father – through his illicit affair with his new wife. Need I write more on this?

After watching his younger self earlier in these vintage Met streams, James Levine now had more of a Buddha-like repose and countenance at the podium. His Met orchestra seemed to play as wonderfully as ever. (Sharon Meekins still was listed as a member of that orchestra before the pandemic stopped all Met performances. She was singled out in the Met archive details of this performance and deserves great credit for her poignant cor anglais contribution to the start of the third act.) Levine’s conducting maintained a consistently beautiful line with a purposeful forward momentum towards the opera’s tragic denouement. Although during the Act II love duet, as well as Tristan’s final act delirium, the tempi could drift, and this drained some of the impact from these scenes. Ben Heppner’s voice had elements of Tristans past and present – notably Jon Vickers and Stephen Gould – but he was no risk taker and it was all so finely-honed it was as if Heppner was reluctant to make an ugly sound even if it would heightened the dramatic impact of what he was singing.

The acting abilities of both Heppner and Eaglen were not tested as they mainly just had to sit down, stand up, or walk a few steps. For instance, Isolde’s final aria ‘Mild und leise’ – that Wagner called the Verklärung (Transfiguration) – was sung out into the audience with her standing behind the flames. It is difficult to 100% trust – through my laptop speakers – the sound I was hearing, and I could only genuinely comment with any great certainly on Eaglen’s voice had I heard this performance live in the theatre. Nevertheless, I believe, for all her laser-sharp top notes the role needed more than that. It required a voice even throughout its range, which Eaglen’s certainly wasn’t at the time. There was the resonance of her middle voice, heard to best effect in the love duet and her dignified and extremely profound final musical summation. Elsewhere, the voice lacked some body and colour, though her extraordinary reserves of power were never in doubt.

I had the pleasure – on separate occasions – of interviewing Heppner and Eaglen and they were wonderful human beings. However, I am sorry to write how I could not warm to, nor believe, in Eaglen as a romantic heroine, however ill-fated. Although both Heppner and Eaglen do not now sing any of the big roles they made their names with, the good news is – unlike several singers I have encountered again recently thanks to these Nightly Met Opera Streams – they are still with us.

Hans-Joachim Ketelsen’s Kurwenal – the loyalist of loyal servants – was uncommonly well-acted and vocally impressive. As Isolde’s errant, though caring, handmaiden Brangäne, Katarina Dalayman – who has sung as both a soprano and mezzo-soprano – was in superb command of her role. Dalayman’s voice was supple and rich and she was a despairing voice in the wildness in Act II. René Pape was the magnanimous King Marke and created the most recognisably human character in this performance. Just listen – if you get the chance – to how his burnished bass brings the deepest sorrow to ‘Da kinderlos einst schwand sein Weib’ (about how his wife dies childless) and the sense of resignation he gave to his final lines in Act II ‘Den unerforschlich tief geheimnisvollen Grund, wer macht der Welt ihn kund?’ which he caressed as if he was singing Lieder.

Jim Pritchard

For more about the Met’s activities before they reopen click here.

Dr. Pritchard, my congratulations for your brilliant appreciation of this unforgetable 1999 Met production. Surely you had an insight of the “mise-en-scène” and performers. Glorious performers. Katarina Dalayman was superb.

Greetings, Murillo Homrich Schirmer-Timm (bass-baritone).