Germany Bayreuth Festival 2013 [3] Wagner, Der fliegende Holländer: soloists, chorus and orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival. Conductor: Christian Thielemann. Bayreuth Festspielhaus, 6.8.2013. (JPr)

Germany Bayreuth Festival 2013 [3] Wagner, Der fliegende Holländer: soloists, chorus and orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival. Conductor: Christian Thielemann. Bayreuth Festspielhaus, 6.8.2013. (JPr)

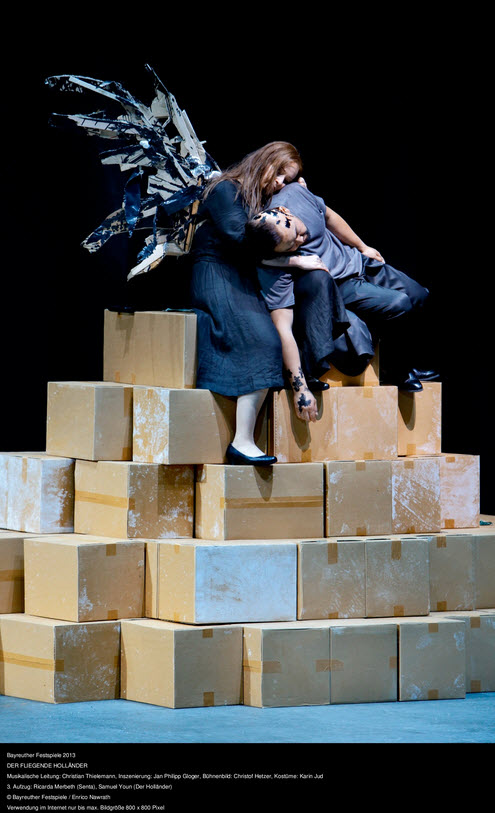

Photo (c) Enrico Nawrath

Production:

Director: Jan Philipp Gloger

Sets: Christof Hetzer

Costumes: Karin Jud

Lighting: Urs Schönebaum

Video: Martin Eidenberger

Cast:

Daland: Franz-Josef Selig

Senta: Ricarda Merbeth

Erik: Tomislav Mužek

Mary: Christa Mayer

Der Steuermann: Benjamin Bruns

Der Holländer: Samuel Youn

The 2012 première of Jan Philipp Gloger’s revisionist new Der fliegende Hollander was mired in the controversy over Evgeny Nikitin’s tattoos and his departure from this production. I saw the last performance of the first season and by that time this had generally been forgotten and many members of the audience took part in a storm of booing as a measure of their unhappiness – to say the least – at the new staging. Once again it is very interesting how such a scandal one year becomes a big success the next … so there is still hope for Frank Castorf and his much disparaged new Ring this year! At this third Holländer performance of the 2013 Festival not a single sound of dissent was heard amongst all the thunderous applause.

The reason is that the ‘Bayreuth Workshop’ has toned everything down somewhat. Originally everything was splattered by red paint. Although we still have something a bit sludgy brown streaking down the walls from time-to-time there is no hint of this now and Senta uses black paint this year. Gloger still raises more questions than he possibly answers even though there is a cogent interview with him in the programme that enlightens the audience about how he deals with the ‘sea’ that is so central to Holländer:

‘We also wanted to find an image for the unrestrained power of the sea, which dominates the score from the very beginning. The sea is a further protagonist in the first act; in his monologue, the Dutchman addresses it as if it is an opponent … the sea stands for a world that surrounds us and that is uncontrollable, highly arbitrary in the way that affects us. Our stage designer, Christof Hetzer, designed an artefact that represents the sea as an image of the world and life, and which, in my opinion, has many associations: a complex data network, an uncontrollable global market, a metropolis seen from the air, maybe also a world of glittering possibilities and never-ending opportunities that entices you to grasp them.’

The legend of course is a simple one: the Dutchman is cursed and cannot die, being condemned to sail endlessly on the world’s oceans seeking redemption by a woman’s eternal love. Gloger translates this as a parable of today’s high-tech world and the search for a profit at all costs. There is no sea, storms or Dutchman’s ship and all we see in Christof Hetzer’s installation that fills the stage as the curtains open is a stream of data crisscrossing the stage with digital displays of seemingly random numbers. Daland, a factory owner, and his zealous bookkeeper, the Steersman, are for some reason ‘all at sea’ in a small rowing boat amongst all this. I remain convinced that the Dutchman and his crew are basically human but have some form of cybernetic implants to connect them to the ‘data network’ and so are part of a hive similar to that fictional alien race, the Borg, from one of the Star Trek TV series.

The Dutchman can only be released from his curse by ‘assimilating’ with the human woman willing to be faithful to him unto death. Until he finds her he remains a lonely figure with more money than sense who is looking for the next big thrill – the next sound investment. He wanders on wheeling his carry-on luggage full of money: he has all the drugs and women his money can buy but he cannot find redemption, nor can he kill himself. This is Wagner’s one-act version and we soon see Daland’s production lines of women checking and packing electric fans. Senta – dressed in black and not red this year – dreams of escaping all this repetitive drudgery and creates her fantasy Dutchman figure – and later a large pair of wings – from bits and pieces of cardboard from off the factory floor. Her on-and-off boyfriend, Erik, is the maintenance man on hand with a glue gun for any quick repair needed. The men and women appear equally integrated into this manufacturing and trading community and the announcement of the men’s’ return – probably from a sales trip – only makes the women work harder under Mary’s constant urging to reach, more quickly, their target of boxes shipped. The ‘sailors’ are therefore business-suited executives bringing their wives and girlfriends to a product launch. The Steersman is in charge of the balance sheet and oversees the party that will soon be invaded by the Dutchman’s cohort.

When the Dutchman and Senta first meet they submit to what destiny has in store for them both. For him the only way to disconnect himself from the ‘global market’ is to burn all his money. He has called Senta ‘an angel’ and she now dons that pair of wings. As in all ‘rom-coms’, with the seemingly ill-matched couple having fallen in love there is the obligatory argument before they are finally united. Here the Dutchman misinterprets Senta’s pity for Erik as affection, and believes all his hopes are at an end. He orders his crew to make ready to depart, although she desperately tries to reassure him of her faithfulness. He wants to save Senta from eternal damnation and since she hasn’t taken her vow in front of God he wants to release her. But Senta does promise herself to him and stabs herself. She is last seen in the arms of the Dutchman on top of a small ziggurat of boxes. The curtains then close temporarily but soon open again to reveal how no opportunity has been lost to cash in on the grief of others and the last tableau shows the factory hard at work producing commemorative figures of the tragic couple’s final pose.

Samuel Youn’s Dutchman lacks intensity and his passive demeanour might be part of Glogler’s conception, requiring this slightly robotic approach. His voice had warmth and a fine legato but none of the individuality that would have genuinely convinced me he was – what his music needs him to be – a ghostly figure, cursed and in despair. For the better, Adrianne Pieczonka was replaced this year by Ricarda Merbeth as an exciting Senta whose full-voiced top notes and impassioned singing totally embodied her character’s compulsion and passion. Repeating their roles from last year were Franz-Josef Selig as the wonderfully venal, yet paternal, Daland; Christa Mayer as the officious factory manager, Mary, and Benjamin Bruns as the hyperactive Steersman. Newcomer Tomislav Mužek ably completed the fine cast as Erik who is in unrequited love with Senta and his feeling of betrayal was very convincingly portrayed and expressed in the few moments Wagner gives him on stage.

I know that Christian Thielemann – Bayreuth’s music advisor – is probably the world’s greatest living Wagner interpreter, however, I remain ambivalent about his Holländer and wished he was conducting something more worthy of him and could do more with. At 130 minutes the performance was over before it had really seemed – in Wagnerian terms – to have begun: I thought it was just a little bland and needed more drama, regardless of how superbly detailed, transparent and natural it all sounded. It was impeccably played by the orchestra but at last there is something to criticise about the chorus – they were their usual magnificent selves but the utterances of the spectral crew let them down through lack of volume and impact.

Jim Pritchard

Click here and here for other recent reviews from the 2013 Bayreuth Festival and an interview with Petra Lang will follow soon.

For more about the Bayreuth Festival visit http://www.bayreuther-festspiele.de/.