United Kingdom A Time There Was (World Premiere), Lexi Hutton (soprano), Alan Oke (tenor), Alex Ashworth (bass-baritone), Jubilee Opera Soloists and Chorus, Jubliee Opera Orchestra / Stuart Bedford (conductor), Jubilee Hall, Aldeburgh, 9.11.2013 (RD).

United Kingdom A Time There Was (World Premiere), Lexi Hutton (soprano), Alan Oke (tenor), Alex Ashworth (bass-baritone), Jubilee Opera Soloists and Chorus, Jubliee Opera Orchestra / Stuart Bedford (conductor), Jubilee Hall, Aldeburgh, 9.11.2013 (RD).

If England has no more gifted Children’s Opera company than Jubilee Opera, whose new Britten stagework A Time there Was has just had its premiere at Britten’s old Jubilee Hall in his home town of Aldeburgh, Suffolk, it’s for many good reasons.

There are rivals who brave these difficult waters, yet none is a patch on Jubilee, which this year celebrates its 25th season, on top form. Some have elements of Jubilee’s passion, earnestness, even tenderness. Few have its precision, pzazz, fire in its belly, emotional range, determination, across-the-board skills from carpenters to wigmakers, or appetite for turning tricky, taxing tricky repertoire into ear-tingling, eye-appetising triumphs. Jubilee can also boast a rosta of modest young regular stars, most aged 14 and under though a few above that, bursting with explosive, joyous, unpredictable musical and dramatic talent.

The company is not flawless. Moments can falter (rarely the music, which is usually on the nub). Yet there was not a hint of weakness when Frederic Wake-Walker staged Hans Krása’s Terezín masterpiece for the Third Reich’s imprisoned wartime Jewish children, Brundibár; or lack of punch when they tackle Noye’s Fludde or St. Nicolas. However, some seasons ago I found their The Happy Prince (Williamson, but without Wake-Walker) disappointingly wet.

Unlike some more self-advertising companies (even, in its early days, National Youth Music Theatre, who while older recently proved their mettle with a breathtakingly danced West Side Story in Manchester), their words usually come across with dazzling clarity (as W8 opera’s recently didn’t). What’s more, Jubilee wouldn’t contemplate miking boys or girls. What is one training young voices for, if not to project and for the joy of the real voice, unbastardised?

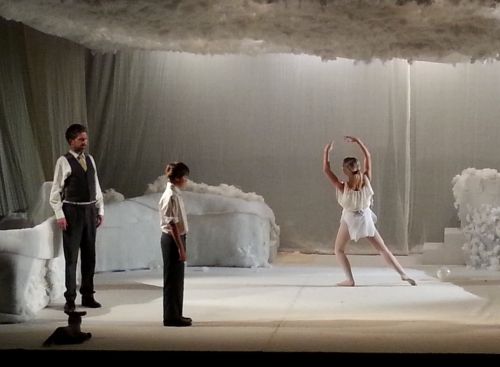

If a couple of scenes of Wake-Walker and Steuart Bedford’s new Britten centenary stagework, A Time there Was (the title belongs to the composer’s op. 90, a powerful, Death in Venice-period Suite on English folk Tunes: ‘Cakes and Ale’, ‘Hunting the Squirrel’, etc.) slightly drooped, most of it – pace the snowbound set – was alight. The idea, fusing extracts from several of Britten’s operas, was to generate some interplay between the Tenor Man, a kind of adult Britten figure (Alan Oke, whose fluent upper tessitura is now to die for), located front of stage amid a cheerful yet meditative desktop clutter – Oke’s aching, cogent, guilt-ridden, redemption-seeking figure looked and sounded ready to burst into Captain Vere, but for the finale sidled onstage to provide an especially vulnerable Peter Quint – and the ‘boys’ of Britten’s operas. He is, in effect, the yearned-for boy grown up.

We didn’t get Thomas Hardy’s train-journeying boy with the violin (surely a rectifiable omission); but rather much else; and when Oke as the grown-up, self-longing boy (a point about pederasty rarely pointed out but patent and even lovable in the composer’s case) sings Coleridge’s ‘Encinctured with a twine of leaves’ from Britten’s Nocturne (‘…A lovely boy was picking fruits…’: ‘But who that beauteous Boy beguil’d, – / That beauteous Boy to linger here?’ we almost forget this is a William Blake-like waif, or the pure cupid of Anna Lea Merritt’s artwork ‘Love Locked Out’, so that here more than anywhere else in this constantly fresh Bedford-Wake-Walker concept the old Britten question begins to surface.

It was one of this show’s most beautiful, sincere, utterly moving moments: is not Britten himself (Oke) the boy whose beauty age (if not prep school), has almost, but not quite, marred?

No fewer than three boys of incipient or huge gifts depict Miles (a nursery song with Flora, the sinister ‘malo’ ditty and Miles’s seeming death); there’s a full-blooded Jack Tars’ chorus from The Golden Vanity; and the deliciously nauseating triad of children from Albert Herring: Amelia Schroeter (Emmie), Eleanor Retey (sister Cis: there is even another talented Cis, Cis O’Boyle, who made lighting an integral part of this show) Add to that thefusion of instinct and intellect which makes William Rose (turned-14-on-the-day) Jubilee’s most strikingly versatile performer, and you have quite a blustering show.

At the end Rose appeared as a scintillating Puck (14 or no, he pulled off ‘If we shadows have offended’ as if he’d been performing it at the RSC for months), and brought the curtain and the house down. They sang ‘Happy Birthday’ to him (and to Britten, who turns 100 on St. Cecilia’s Day, 22 November) in a tacked-on, Ben-like envoi: as a child performer Will, who by the age of eight was decked out as Brundibár’s Chief of Police, look like going on for ever.

12-year-old Alfie Evans, his abilities on the professional stage proven in a riveting sequence from Wake-Walker’s The Burning Fiery Furnace at this summer’s Aldeburgh Festival, sang malo with aching poignancy; he really would, you felt, rather be in an apple tree than in this psychosexual muddle. His same-age namesake, Lucas Evans (no relation), was vocally the most gorgeous Miles I have ever heard – and I’ve heard some very good ones. As the Royal Academy’s Jane Glover once observed, ‘Have you ever seen a bad Miles?’ No, but I’ve heard some. This with its somewhat alto overtone and undertow, was pure gold, enough to stop one’s heart in its tracks.

Which makes the end, which I can give away, a wonderful paradox: this purest of young Mileses revives and walks away, leaving Quint and the Governess to their mutual mélange of free love and female political correctness. One always knew Miles was a Quint at heart, but Wake-Walker really astonished you with his unexpected invention; and Evans – to my surprise – carried his resurrection off visually too. He moves with poise but not pose: as so often in this new work, it was the simplest things that counted most.

Owls and Herons, Doves and Chaffinches looked after the younger members, much as in Orlando Gough’s glittering Road Rage community opera at this summer’s Garsington. One of the best visual moments was when the ship Golden Vanity suddenly appeared before our eyes, an exciting impact from designer Shizuka Hariu even though the brilliantly contrived snow scene – essential early on – gradually, except when relieved by coloured (e.g. pink) light, felt a bit omnipresent. Thouigh this year’s were simple too, Jubilee’s costumes are always fabulous, and apt. We owed that here to Kitty Callister. If you’re seven or nine, it must feel terrific to be part of such a well-kitted, beautifully-marshalled outfit.

The orchestra, not least strings (often exposed in long sequences) worked musical wonders under Steuart Bedford, Britten’s masterly one-time amanuensis. The cor anglais (Tjadina Würdinger) for Miles’s Malo, and twin harps (what a luxury, in a musically satisfying, serviceable but perhaps improvable pit) were stunning, and extracts from A Midsummer Night’s Dream just glorious. 16 year old Jamie Rose’s (‘Trip Away, Make no stay, Meet me all by break of day’) – Oberon’s bedtime lullaby – was sung in the most beautiful professional-standard countertenor: not yet a Bowman or David Daniels or Iestyn Davies maybe; but on the way to a Deller: to have such exquisite, roseate tone is an enviable gift to be treasured.

Lucas Evans’ Miles was prefaced by he and Oke singing the tenor-alto duet from Abraham and Isaa – again, Evans’s low tessitura sounded miraculous. The paired unison was heartrending, and the way this melted into Miles’s sign-off, ‘So, my dear, we are alone’ was one of the other most expressive details of the whole new concept. (Alexandra Hutton sang the mother/governess/music mistress roles vividly, if initially forcefully; it was anachronistic, maybe deliberately so, for Harry, bursting for the loo, to address her as ‘teacher’; Alex Ashworth was the firm, underused baritone ‘father’ figure).

Even with instructive programme notes I’m not sure I quite grasped how it hung together, rather than stimulated as a series of stunning, surreally-connecting vignettes. To separate well known scenes and reimagine them apart from each opera whence they derive is hard for an audience. Yet the picture on the cover (boy maybe not lost in, but penetrating, eerie pinewoods) said it all. No more nursery: visceral new beginnings. The feeling of the Tenor Man trapped by his inability to return to childhood: infant play, childish frolics, first sexual awakenings, self-emancipation as an individual: these were very strong.

Recasting the Henry James ambivalent ending as (from the man’s perspective) the death not of the child but of childhood (hence this boy survives, albeit shorn of childhood and already heading for the office) is utter common sense.

‘Why do we weep,’ Wake-Walker enquires, ‘when a man is dead and gone While noone weeps as youth drops its petals one by one?’ Well, the youth sometimes weeps, and Oke’s Tenor Man clearly does. Utterly benign even as Quint, he returns to suckle the Governess and caress his fled boyhood self-image, tragically acquiescing in his own bereftness (‘I seek a friend..’). Lucas’s Miles may end up a Marquess, or a Brady. Free will – trumpeted by both King’s Navy in The Golden Vanity, crucial to Owen Wingrave, is what the Screw is subliminally about: problematically typified by Quint, nearly crushed by the Governess. Jung would have approved the individuating spirit and imagination of this brave and exploratory new piece.

Roderic Dunnett