Italy Puccini, La bohème: Soloists, Gaulitanus Choir (directed by Colin Attard), children’s choir (directed by Agnese Carrubba), Symphony Orchestra of the Grand Theatre of Lanzhou / Li Xincao (conductor). Live to Cineworld Basildon from the Ancient Theatre of Taormina, Italy, 5.7.2017. (JPr)

Italy Puccini, La bohème: Soloists, Gaulitanus Choir (directed by Colin Attard), children’s choir (directed by Agnese Carrubba), Symphony Orchestra of the Grand Theatre of Lanzhou / Li Xincao (conductor). Live to Cineworld Basildon from the Ancient Theatre of Taormina, Italy, 5.7.2017. (JPr)

Cast:

Mimì – Karen Gardeazabal

Rodolfo – Georgy Vasiliev

Marcello – Fabio Capitanucci

Musetta – Bing Bing Wang

Schaunard – Francesco Baiocchi

Colline – Stanislav Chernenkov

Benoît – Angelo Nardinocchi

Alcindoro – Giovanni Di Mare

Parpignol – Filippo Micale

Production:

Stage and cinema director and sets designs – Enrico Castiglione

Costumes – Sonia Cammarata

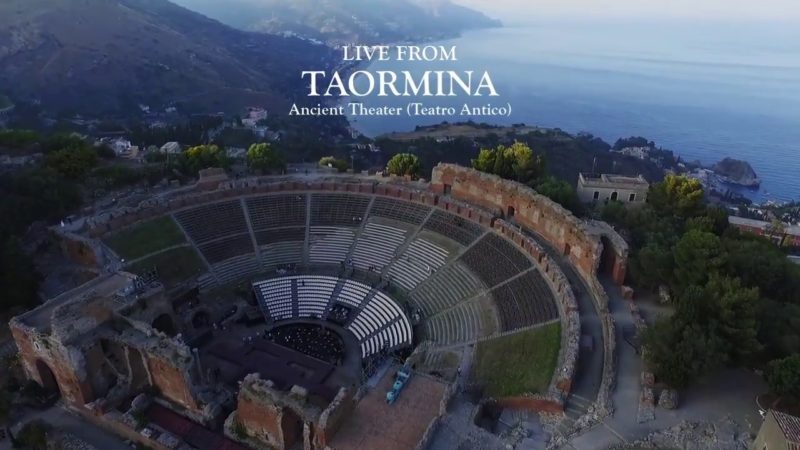

The Ancient theatre of Taormina (Teatro antico di Taormina) is a Greek theatre, on the east coast of Sicily in the shadow of the gently smoking volcano, Mount Etna. It was built in the third century BC and was reconstructed over subsequent centuries to give it the Roman appearance it has today. The building reached a maximum diameter of 109 meters, with an orchestra with a diameter of 35 meters and a capacity of several thousand. In antiquity it has seen extravagantly staged fights between gladiators and wild animals, but since the 1950s the theatre has been used for more gentler entertainment including award ceremonies, opera, ballet, concerts, plays and the annual festivals, Taormina Arte and Taormina Film Fest. The theatre also featured in Woody Allen’s 1995 film Mighty Aphrodite.

La bohème was Puccini’s fourth opera for the stage. It was produced at Turin in 1896, and was not an instant hit with the critics. It has gained in popularlty of course over the last hundred years and more, so much so, that – although I had been expecting this performance to be one of Basildon’s best-kept secrets – it drew a big crowd to my usual Cineworld cinema.

The source material of librettists, Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, was Murger’s novel Scènes de la vie de bohème. They selected four of the characteristic episodes and imbued them with the spirit of the original. Though set in Paris about 1820, the story is a timeless one which can have contemporary resonances which modern stage directors can exploit, though not here as you will see. Far too many people believe that a composer’s output evolves in isolation from their personal life and the world in which they live, but this certainly was not the case for Puccini since he is another composer whose masterpieces can be biographical in nature. In La bohème there is the reminiscence of the compoer’s own student days, sharing a room in Milan with Mascagni, and probably recalling something about lost love too. Indeed his graduation exercise from the Milan Conservatoire, Capriccio sinfonico, is the first music we hear as the curtain rises – or, as here, the lights go up – for La bohème.

Certain elements of Puccini’s musical style help to confirm La bohème as the masterpiece it undoubtedly is. Puccini appears more open to the concept of symphonic development of the German masters than other Italian opera composers (Verdi especially). Based on this idea, Act II has been considered the ‘scherzo’ and Act III the ‘slow movement’. There is a greater sense of La bohème and his other operas being ‘through-composed’ just as one might hear in a movement from a symphony. (Peforming it at Taormina with only minimal pauses between acts and one brief interval did much to emphasise this.) We know only too well that certain arias (for instance, ’Che gelida manina’ and ’Si, Mi chiamano Mimì’) and ensembles can be taken out of their original context and performed on their own. Yet the opera in full contains very little sense of having ‘numbers’, as are found in Verdi’s operas up to Otello and Falstaff. Perhaps more importantly, Puccini uses something called ‘thematic reminiscence’ that is not far removed from Wagner’s leitmotifs. Here in La bohème, there are themes associated with the bohemians and with Mimì, among others.

There were apparently only two performances of La bohème at Taormina and this was the first of them. I might be proved wrong, but this seems to have been staged especially for Taormina and therefore was a remarkable achievement. I have just responded to a comment on this website bemoaning the ’pretentious idea of modern relevance’ from an opera director. Had that correspondent seen this performance she would have been delighted by Enrico Castiglione’s staging. Obviously he took his inspiration from the grandeur of the theatre the opera was being performed in and there were blocks of the local Taormina stone – which it is built from – massed as a wall on the stage, with a few just lying around and used as tables. This stone looked real enough, though I suspect it wasn’t. Few other props were seen over the four acts apart from a few chairs and a brazier made of an old oil drum. I suspect the costumes were mostly the singers own and included a suitably long brown overcoat for Colline, whilst Marcello had an elaborately embroidered (it seemed) jerkin and Musetta appeared already dressed for the aftershow party or ready to go clubbing. Enrico Castiglione was responsible for almost all we saw on stage or on screen and brought a wonderful sense of cinematic-style realism to the cast, chorus and extras. It was all unashamedly old-fashioned – and very familiar – but it worked splendidly.

None of the singers are particularly familiar to British audiences apart from Fabio Capitanucci’s Marcello a role he has sung at Covent Garden (for a review click here). I saw him a few times that year and he was not as good on this occasion. He oversung the part as if he was in the much larger Verona Arena and his stand-and-deliver performance was at odds with the more nuanced acting around him. Straddling a chair Sally Bowles-like in Act II, Bing Bing Wang caught the eye – if not the ear – as Musetta. Her ’Quando me’n vo’ was rather poorly supported, though Wang was much better when praying for Mimì near the end. Benoît (Angelo Nardinocchi) and Alcindoro (Giovanni Di Mare) were particularly well characterised with the latter, on this occasion, far from the usual ’old chump’ of the libretto.

Overall the bohemians were an enaging quartet who it was a pleasure to spend some time with. Francesco Baiocchi was an engaging Schaunard and Colline’s ’Old coat’ aria was sung simply and with unaffected gravitas. Georgy Vasiliev’s likeable Rodolfo had the curly-haired Byronic look of Jonas Kaufmann and he has – to his credit – the more natural voice. He very occasionally showed signs he was pushing his voice a little too much, though mostly he sang with an ardent tone and refined lyricism. Amongst a cast of mixed nationalities it was Mexican soprano Karen Gardeazabal who stood out. Hers was a convincing, vulnerable and intensely sung Mimì and there was an appealing sense of genuine chemistry with Rodolfo, which isn’t always the case.

As always it is not easy to judge the quality of the orchestra through cinema speakers but the sound – which seemed a bit thin to begin with – improved during the evening. Lin Xincao appeared to conduct his Lanzhou musicians, the soloists and the splendid combined choruses with idiomatic Puccini conviction and passion. There were a number of wonderfully sounding moments, particularly from the moment Rodolfo and Mimì are alone at last in Act IV through to her deeply affecting death, here on a rug on the floor of the stage. That in itself would have made a trip to sultry Taormina worthwhile … as it was I only had to go to air-conditioned Basildon!

Jim Pritchard

For more about CinemaLive events at your local cinema click here.