United States Mozart, Mahler: Menahem Pressler (piano), Janai Brugger (soprano), Philadelphia Orchestra / Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla (conductor), Verizon Hall, Kimmel Center, Philadelphia, 10.2.2018. (BJ)

United States Mozart, Mahler: Menahem Pressler (piano), Janai Brugger (soprano), Philadelphia Orchestra / Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla (conductor), Verizon Hall, Kimmel Center, Philadelphia, 10.2.2018. (BJ)

Mozart – Piano Concerto No.23 in A major, K.488

Mahler – Symphony No.4

Since she was appointed music director of Britain’s City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra — Simon Rattle’s old orchestra — in February 2016 at the age of 29, Lithuanian-born Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla has been developing a reputation for herself that is described in often rapturous terms. This, her debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra, offered a program well calculated to test the mettle of any conductor. Was all the hype, I wondered in advance, justified?

Well, whether the times I have encountered Mahler’s Fourth Symphony in concerts or in recordings over the years may be said to number in the triple-digit range or merely among the upper double-digits, what I heard on this occasion was simply the greatest performance of the work I have ever heard. In a year when the musical world is widely celebrating the centenary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth, it is perhaps only natural for me to think first of that conductor’s interpretation, which has ranked for years as the most sympathetic, insightful, and stylish view of the Fourth in my experience—and Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla’s performance indeed struck me as what might be called ‘Bernsteinian’ for two specific reasons.

The less important of those reasons is merely that her podium deportment displays a physical exuberance vividly reminiscent of Bernstein—a penchant for broad gestures, wide swaying motions, and even leaps. More significant by far is the eager spontaneity with which the Maestra responds to the frequently spasmodic, wild, and even startling changes of tempo, dynamics, articulation, and mood called for in Mahler’s score—a spontaneity and willingness to embrace extremes for which Bernstein has hitherto provided the benchmark. In that regard I think Gražinytė-Tyla may be said to have gone beyond him.

If noting such fidelity to a musical element that was central to Bernstein’s art constitutes in some degree a value judgment, so be it. But while this performance shared with Bernstein that touch of sheer interpretative devilry, it was also notable in combining such extremes with a delicacy of texture, phrasing, and tone-production even more impressive than her great predecessor’s virtues in those areas.

There was something else in her performance that brought to mind another great musician whose name began with ‘B.’ I remember a recording of another A-major concerto by Mozart (K.414) of which a critic remarked years ago that it sounded as fresh as if the soloist/conductor, none other than Benjamin Britten, had written the work himself, and had furthermore written it that morning. Throughout this performance by Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, but especially in the first two movements, I was constantly being struck by the feeling, not only that she had not written the symphony down from her own mental dictation, but that she was making up every aspect of it as she went along.

After a similarly stimulating traversal of the intermittently diabolical scherzo, we came to the most magical part of the whole performance. The slow movement, which in this case stands third, brought a pianissimo of a subtlety and yet a clarity such as you are not likely to experience more than once in a lifetime of concert-going.

In all these passages, the insights of pacing and texture were reinforced by a sensitivity to instrumental timbre that was comparably beyond praise. The clarinets sounded more liquidly clarinettish than ever, Daniel Matsukawa’s bassoon more bassoony; the horn section offered one stirring entry after another; and the upper strings were as lightly airy in sound and as quicksilver in articulation as you could have wished.

My only slight disappointment came with the finale. It too was expertly paced and superbly played, but I thought it was a mistake on the conductor’s part to station the soprano soloist halfway back on stage right—a position from where, instead of floating out through the hall like an easeful benison, Chicago native Janai Brugger’s evidently lovely voice was able to penetrate a relatively light orchestral texture only with some difficulty.

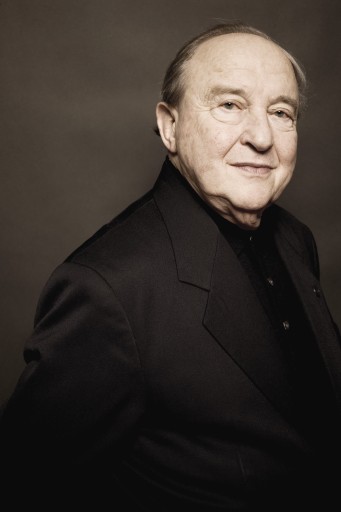

A tiny complaint in the context of so spectacular a debut, and on a day when the collaboration in a great Mozart concerto of a young genius of the baton with a distinguished pianist 63 years her senior could easily have provoked reams of praise from any halfway sensitive critic. The muscular power of his playing by now inevitably somewhat diminished at the age of 94, Menahem Pressler was nevertheless still able to give a well-rounded performance of Mozart’s K.488 concerto (a good choice in view of its relatively gentle tone). And the lambent tonal gleam and aristocratic phrasing he brought alike to the slow movement of the Mozart concerto and to his Chopin encore beautifully illuminated the closeness of the Polish composer’s spirit to that of his idolized forerunner.

Bernard Jacobson