A Review of the Documentary film Nureyev Released Worldwide in Cinemas on 25 September

**** NUREYEV

I suspect it was because of the proximity of my birthday that I was taken to Covent Garden on 13th January 1977 to see The Nutcracker and encountered – and was captivated by – the dancing of Rudolf Nureyev for the first time. In typical fashion his production revised the original plot to give it a psychoanalytic twist and now Drosselmeyer and the Prince were one and the same. (They represented the ideal man the pubescent heroine, Clara, dreams of now she is on the cusp of becoming a teenager.) After seeing innumerable performances throughout Britain and in Vienna, the last time I saw Nureyev dance in London for the Royal Ballet was on 9th January eleven years later and, sadly, his masterly Albrecht – when he partnered his protégé Sylvie Guillem in Giselle – was almost exactly five years before his premature death at 54 in 1993, from Aids.

It would not be in my nature to suggest I was ever consumed by the ‘Rudimania’ which surrounded him and his performances especially in the ‘golden years’. Nevertheless, he began my lifelong interest in ballet and – to a degree – it is the hope that I will experience the anticipation, visceral excitement and drama of many of those bygone evenings that draws me back to the art form time and again.

Bafta-nominated Jacqui and David Morris’s documentary Nureyev (from Rattling Stick and Little Compton Films and currently on cinema release) does much to bring happy memories of the late-1970s and the ‘80s flooding back. Made with the support of the Nureyev Foundation this is a deeply respectful look back at his Tartar heritage, the deprivations his family went through as he was growing up during the Second World War, his defiance of his father’s wishes that he not study ballet, his early days at the Kirov Ballet, the infamous ‘leap to freedom’, international superstardom and, especially, his partnerships – in differing ways – with Erik Bruhn and Margot Fonteyn. It was pleasantly devoid of any voyeuristic examination of Nureyev’s darker side either in the theatre or in his personal life. The suggestion is that he was simply unlucky, an unwitting victim of his sexuality and the ‘bathhouse scene’ of the laissez-faire 1980s when there was a ‘terrible virus’ being ‘spread unknowingly’. The film ends with one of the last of its innumerable intertitles with the chilling message of how ‘Aids has not gone away’. Suggesting whilst it is not now the death sentence in the West that it was, that is unfortunately still not the situation everywhere the world.

From the moment the film opens with a montage of historical footage of Tsar Nicholas II, Stalin, the Russian Revolution and Anna Pavlova’s ‘Dying Swan’ it was another way of showing how Nureyev was moulded by the times he lived through. One of the film’s disembodied contributors revealed how the Cold War involved competition between the U.S. and Russia politically, militarily and, importantly, culturally. When Nureyev’s personal success in Paris undermined the success of the Kirov company it was deemed necessary to send him back to Russia, and so he defected on 16th June 1961. We heard how this happened two months after Yuri Gagarin orbited the Earth, and two months before the Berlin Wall went up. As Nureyev himself once said – though this is not used in the film ‘I left USSR when the construction of the Berlin Wall had begun and returned when it was demolished’ since – as the film shows – a week after the fall of the Wall, Nureyev danced in Russia for the first time since his defection, 28 years earlier.

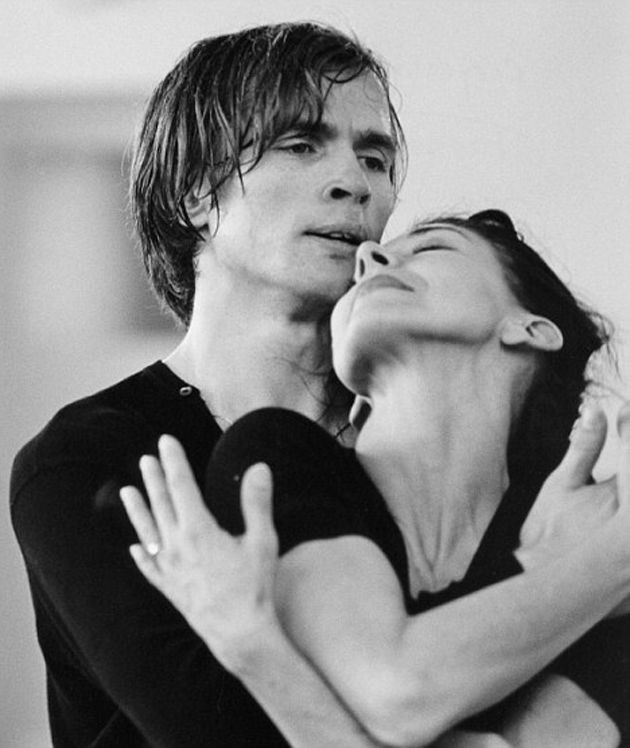

One of the glories of Nureyev is the archive footage, whether it is seeing him in his prime prowling the stage – Nureyev is often described as a ‘panther’ in the film – or in filmed interviews or private moments or in more intimate ones, such as the deeply-moving meeting in 1989 with his first ballet teacher Anna Udeltsova – then over 100 years old – for the first time after nearly three decades. Where no material existed the Morrises filled in Nureyev’s story with some expressive modern dance interludes (choreographed by Russell Maliphant) mostly in time-appropriate costumes recreating Nureyev’s early years with his parents or other important subsequent events in an eventful life.

Obviously for someone like me I knew most of what I saw during Nureyev, through the contextualising of it from a political and social perspective kept my attention throughout the 110 mins running time. It is wonderfully edited and the choice of music – including Alex Baranowski’s haunting original compositions – was very appropriate. If we were not hearing from Nureyev himself, I did become a little perplexed why his own words were read by Dame Siân Phillips. Another minor quibble is that Nureyev’s influence on the role of the male dancer – and indeed his legacy – remained largely unexplored. It was mentioned he was accused of wiping out ‘a whole generation of English dancers’, yet no more was said.

To be truthful, the film’s first caption and then some words we hear from Sir Yehudi Menuhin revealed all we need to know about Nureyev. The first of many eclectically chosen quotations we are shown was by Napoleon Bonaparte: ‘Great people are meteors designed to burn so that the earth may be lighted.’ Menuhin said ‘Nureyev was the human panther. He had that incredible animal greatness and power; at the same time, he was a human being. It is something that lends an intensity of presence which is overwhelming, but the great vast audience is always fascinated by the superhuman man. He was a phenomenon and he knew it of course, and sometimes he knew it too well … Sadly destiny allowed him to consume himself and live to the hilt.’

There is undoubted sadness at how his life ended and although time may even rob me eventually of my memories of Nureyev, I am still glad to remember him now in good – and even not so good – times. What I hope most of all is that this film, and the forthcoming Ralph Fiennes-directed drama The White Crow (about that ‘leap to freedom’), can both reach audiences who are too young to know very much about Nureyev and will now get the chance to see his uniqueness as a man and a dancer, and so understand what all the fuss was about!

Jim Pritchard

For the Nureyev trailer click here. For more information about screening dates and tickets please go to: www.nureyevthefilm.com.

Facebook @NureyevtheFilm

Twitter @nureyevthefilm

Instagram nureyevthefilm