Austria Wagner, Parsifal: Soloists, Nikolay Sidorenko (actor), Chorus and Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Philippe Jordan (conductor). Filmed (directed by Michael Beyer) at the Vienna State Opera on 11.4.2021 and streamed on ARTE Concert (available until 17.7.2021 click here). (JPr)

Austria Wagner, Parsifal: Soloists, Nikolay Sidorenko (actor), Chorus and Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Philippe Jordan (conductor). Filmed (directed by Michael Beyer) at the Vienna State Opera on 11.4.2021 and streamed on ARTE Concert (available until 17.7.2021 click here). (JPr)

Production:

Direction, Stage and Costume design – Kirill Serebrennikov

Lighting – Franck Evin

Co-director – Evgeny Kulagin

Stage design collaboration – Olga Pavliuk

Costume collaboration – Tanya Dolmatovskaya

Musical assistant to Kirill Serebrennikov – Daniil Orlov

Stunt choreography – Ran Braun

Photo and Video design – Aleksey Fokin, Yurii Karih

Dramaturgy – Sergio Morabito

Chorus director – Thomas Lang

Cast included:

Parsifal – Jonas Kaufmann

Gurnemanz – Georg Zeppenfeld

Amfortas – Ludovic Tézier

Kundry – Elīna Garanča

Klingsor – Wolfgang Koch

Titurel – Stefan Cerny

First Squire – Patricia Nolz

Second Squire – Stephanie Maitland

Third Squire – Daniel Jenz

Fourth Squire – Angelo Pollak

First Grail Knight – Carlos Osuna

Second Knight of the Grail – Erik Van Heyningen

The then Parsifal – Nikolay Sidorenko

Russian theatre and film director – and critic of Vladimir Putin – Kirill Serebrennikov directed this new Parsifal online while still confined to Moscow, though not under the house arrest from which he was released not too long ago after over three years. Serebrennikov’s Parsifal is a harrowing, intense drama that once seen cannot be ignored or forgotten. I saw the first act without subtitles – though I have seen the opera enough times to know what is being sung – and it was really dark and engrossing. However, with the subtitles for the other acts I began to find the divergence between Wagner’s text and Serebrennikov’s stage action rather jarring. Forgive me but it is possible that whatever opera Vienna had offered Serebrennikov to direct would also have been partly autobiographical or cast a shadow on Russia under its current regime. Serebrennikov’s Konzept seems to have been imposed on Wagner’s Parsifal rather than evolving from it. Nevertheless my ‘interpretation’ of what I saw suggests incarceration and brutality ends in redemptive liberation thanks to Parsifal’s journey towards compassionate self-awareness.

During the prelude we see the older Parsifal (Jonas Kaufmann) morph into the ‘then Parsifal’ (Nikolay Sidorenko) and in a snowy, somewhat post-apocalyptic Russian wasteland there is a prominent disused church to which we will return on film throughout this Parsifal and it probably substitutes for the modern-day prison (called ‘Montsalvat’) we will soon be introduced to. This is yet another new opera production created with watching on a screen (TV or computer) firmly in mind. Photos and close-up video work on three screens above the stage reflect life in the prison (subsequently there will be the almost obligatory shower scene!) and introduce us to the culture of tattooing amongst Russian criminals. (Most prominently we will see a barbed wire one around a prisoner’s forehead, a grail, a spear and swan’s wings on others.) We see an older Parsifal reliving his misbegotten youth (by often mouthing other characters’ words!) as one of the inmates and ‘here time becomes space’ as ‘then Parsifal’ will be the silent avatar with whom he often interacts as his story unfolds.

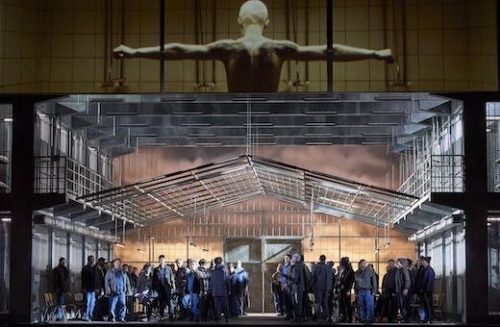

Prisoners emerge Fidelio-like into a courtyard to exercise, and a miasma of testosterone soon emanates from the laptop screen along with the suggestion of homoeroticism because of all the macho posturing and comparing muscles and tattoos. Guards are blatantly smuggling in contraband and so too does a silver-haired, yet striking, Kundry, there as a photojournalist getting background for an article. She also brings in medication for Amfortas who is an enfeebled political prisoner protesting by self-harming which gives him a certain status within the prison. We will later see how he is nearly driven mad by inner voices (Titurel’s?) to ‘reveal the Grail’, though I am not entirely sure what Serebrennikov’s grail is.

Gurnemanz is the prison’s éminence grise and tattoo artist(!) who reveals it is the machinations of Klingsor (later shown as a magazine editor) who is responsible for Amfortas’s circumstances. He suggests the prison community’s redemption will be through ‘the pure fool’. The callow ‘then Parsifal’ is shown killing a fellow prisoner – an albino with an elaborate swan tattoo – and he will show an increasing predilection to violence as the act goes on. (If you can’t beat them, join them!) Not even the sight of an anguished Amfortas can quell his incipient rage; we see Amfortas in his communal prison cell yearning for release, but he is prevented from cutting himself further. Oddly, we will see the guards finding a grail when checking the prisoners’ mail. The act ends with the ‘then Parsifal’ – having learnt nothing from Amfortas’s travails – stripped to the waist and on his way to becoming Montsalvat prison’s ‘poster boy’.

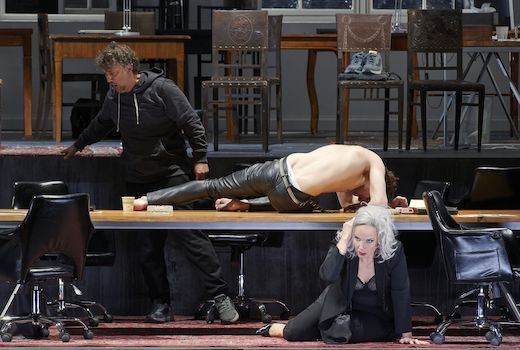

It appears that Kundry is actually the features editor of Schloss magazine whose publisher is the rather sleazy Klingsor who has a hands-on(!) approach to all his female staff. Wagner’s Flowermaidens are now some other journalists, photographers, assistants, stylists or cleaners. Lighting for their office is provided by a large neon halo above and there is also a Perspex crucifix on a side wall. Although this makes some sense in the context of Act I this setting becomes – initially anyway – rather cluttered and of course has nothing to do with mentions of weapons, blood and lovers wounded in a castle! Having been released from prison it is clear ‘then Parsifal’ is to be the glamour magazine’s new cover star thanks to Kundry’s feature on conditions inside Montsalvat. As the older Parsifal tries to engage with his younger self it is as if he is there but not there, though they do swop at one point for him to recall being the object of the office staff’s attention through selfies and requests for autographs.

Kundry sets her sights on the (initially) bare-chested ‘then Parsifal’ and has conjured up three visions of the mother he loved yet abandoned for a criminal career and who died heartbroken. Parsifal sings ‘What was going on in my head?’ and this is the crux of Serebrennikov’s production. Parsifal is offered the consolation of his mother’s blessing and love’s first kiss as Kundry is eager to consummate her seduction of him on the large conference table. He seems compliant at first though the sight of Amfortas reminds him of how he was manipulated by Kundry. She doesn’t take rejection well and threatens him with a gun. Kundry faces off against the older Parsifal who does not fear her and unable to shoot him she guns down Klingsor as the lights go out at Schloss.

Many years have obviously passed as we see the young Parsifal retracing his steps to a derelict church/prison. There is no evidence of enforced detention and we just see women at sewing machines or making crucifixes. (It is notable how the images shown above the stage have diminished in importance during the second and third acts.) Gurnemanz is there and recognises an aged Kundry amongst the women though still very much an outcast. Parsifal stumbles in possibly spoiling for a fight before he realises this is where he was as a feral young man. (Wagner’s Holy Spear is no more now than a length of metal pipe.) Gurnemanz believes Parsifal can turn his life around and bring hope to all those wrongly – or not so wrongly – imprisoned everywhere and he aims to remove the burden of all guilt from him. The women with their loved ones still locked up somewhere venerate Parsifal as their saviour; he gets a ritual cleansing along with a clean white shirt. ‘Das is Karfreitagszauber’ finds Parsifal surrounded by candles, crosses and garlands. Kundry reunites with the ‘then Parsifal’ before everyone gathers their belongings and moves out.

Film of scuffles between prisoners transports us back to the prison courtyard as in Act I. Clutching the urn containing Titurel’s ashes, Amfortas is seeking an end to his suffering. He is losing his grip on reality as he smears ashes on himself and throw them about before he is ‘released’ along with all the other inmates as both Parsifals work together to open all the cells. The back gates are then opened wide and everyone is free at last, and even the ‘white swan’ is shown coming back to life. Kundry leaves comforting Amfortas, and Gurnemanz is shown unsure of which way to turn. Left alone the older Parsifal reflects on the enormity of his life story.

It is important to concentrate on what was seen rather than heard because I was not in the opera house and must trust what the sound engineers allow me to hear. For me Jonas Kaufmann is not a Parsifal and it is difficult to imagine him singing the role in the increasingly unlikely event of ever seeing again a more ‘traditional’ production, such as, the August Everding and Jürgen Rose 1979 Vienna one I saw many times. It is not that Kaufmann sang badly (quite the contrary!) but his dark, burnished baritonal timbre is more suited to Siegmund, Tristan and, maybe, Siegfried than Parsifal which – I believe – needs a much brighter sound. (Serebrennikov’s Parsifal appears to have been devised to accommodate Kaufmann’s characteristic grizzled appearance and might have worked better if a younger, virile voiced Parsifal could have been found to actually sing the role with the older Parsifal staying silent.)

Georg Zeppenfeld’s Gurnemanz is a known quantity, and he is probably preeminent in this role amongst the current generation of its interpreters. Zeppenfeld sang with robust tone and dramatic command; unleashing phrases of majestic beauty as he celebrated nature’s restored innocence in the third act.

Elsewhere there were a series of role debuts in the leading roles led by Elīna Garanča as Kundry. She superbly personified a domineering maneater and sang with her distinctive dusky mezzo with glints of steel though they were ‘glints’ only such as for her viscerally chilling ‘Lachte!’; the only occasion when she really let herself go vocally. Ludovic Tézier’s Amfortas was someone deeply tormented and whose suffering rarely left his face making this an outstanding physical performance which was sometimes difficult to watch. Stefan Cerny was an eerie, incorporeal Titurel and Wolfgang Koch – who is a vastly experienced Wagnerian – sung and played an alcohol-swilling, predatory Klingsor with gusto. There were also no weak links in either the Squires, Knights or Flowermaidens. Finally, the (maskless) men’s chorus sang robustly with clarion power and the women in Act I sounded suitably radiant and exalted.

Michael Beyer’s TV direction did distract from Serebrennikov’s cinematic Parsifal with too many shots of the stiff-backed Philippe Jordan’s sharply angular conducting. However, the results Vienna State Opera’s new music director achieved from the orchestra (members of the Vienna Philharmonic) were exceptional and their Parsifal had a searching, transcendental, luminous beauty frequently at – not unexpected – odds with the stage pictures. Pauses were occasionally lingered over but there were no other longueurs in the well-paced account.

Jim Pritchard

For more about Vienna State Opera click here.

Congratulations! This was an excellent review and I share the views presented. This is one of those new performances that are better heard than seen. Garanča was a superb Kundry, both, acting and singing!

Utter cr*p totally against Wagner’s ideas He must be turning in his grave. I would not go to see it if they paid me!

The GREATEST mise-en-scène after Richard Jones for Opera Bastille!! Parsifal is NOT a religious ceremony: it is an opera based in a story that NEVER took place. You are free not to see it. This production is the work of a genius. Congratulations, Kirill!! Wagner is dead. Forget about him and what his monster ego could have thought.