Bach (and others), Debussy, Fauré, Chopin: Stephen De Pledge (piano). Old Library, Whangarei, New Zealand, 12.6.2021. (PSe)

Bach (and others), Debussy, Fauré, Chopin: Stephen De Pledge (piano). Old Library, Whangarei, New Zealand, 12.6.2021. (PSe)

J.S. Bach and others – A New Zealand Partita (four excerpts)

Debussy – ‘Feuilles mortes’ (Préludes, Book 2), ‘Des Pas sur la Neige’ (Préludes, Book 1); ‘The Little Shepherd’ (Children’s Corner); ‘Clair de Lune’ (Suite Bergamasque)

Fauré – Nocturne No.4 in E flat

Improvisation

Chopin – Ballade No.3 in A flat; Polonaise Op.53, ‘Heroic’

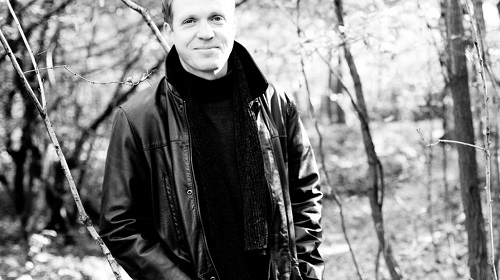

I need hardly say that the Covid-19 pandemic has laid waste to the plans and endeavours of vast numbers of people, or that many of those people are musicians. New Zealander Stephen De Pledge, who has a considerable international presence, is just one of them. For 2020, his 50th. year, he had planned a big celebratory recital tour of NZ with programmes compiled from his favourite pieces. As it happened, NZ’s initial lockdown (which, please note, coincided with the start of our concert season) and subsequent periods of restrictions, although not as severe as those in other parts of the world, nevertheless reduced that tour to just one recital.

Like others, Stephen found some compensation in the option of internet streaming. However, he was thrilled beyond measure to discover that the very few live performances that were possible, by that same token became for him exceptionally special events. This year, with NZ’s Covid-19 community transmission continuing at around zero (so far), Stephen is back on the road, with programmes retaining much of the self-indulgent (his adjective, not mine!) ‘these are a few of my favourite things’ theme.

This programme, the second of a season of four Whangarei Music Society presentations, was played to a very full house (extra seating required). It included two particularly intriguing items, the first of which opened the proceedings. A New Zealand Partita pairs the seven movements of Bach’s Keyboard Partita No.3 BWV827 with responsive pieces commissioned from seven NZ composers. I can see the point of making explicit the pervasive influence of Bach on the subsequent history of music, but whether, as has been suggested elsewhere, this constitutes a ‘re-imagining of this 18th-century musical form for the 21st century’ I leave for you to judge (you can hear the whole work on Youtube). We heard a selection of four pairs (responding Kiwi composers named in parentheses): 1. Fantasia (Leonie Holmes), 2. Allemande (Chris Gendall), 5. Burlesca (Juliet Palmer), 3. Corrente (Christopher Norton). I gather that the only constraint placed on the NZ composers was that their responses should, not unreasonably, make use of something of the Bach source movement.

How music conceived for a ‘plectral’ keyboard should be played on a ‘hammer’ keyboard has long been a bone of contention. (I know that I seem to be having a running battle with myself over it – for example, see my review which considers the approach of another Kiwi, Tony Chen Lin, to the performance of Bach on the modern piano.) One knotty question that I have so far overlooked is the allied one of the composer’s expressive markings. If he doesn’t specify any, is that because he wants the music to be played ‘dead straight’, or is he leaving expression to the discretion of his interpreters? Far from helping, the Big Divide between the pre-Classical, when composers typically made no indications of expression, and the post-Classical, when they indicated expression in ever-increasing detail, considerably muddies the water. But one thing is a racing certainty: whatever tack a pianist takes, he is bound to get somebody’s back up!

Stephen’s approach to Bach was expressive, but with a discreet degree of moderation that considerately stopped short of aggravating my hackles. His Fantasia was quite literally a fantasy, flexibly contouring the hills and dales implicit in the music, yet never to the detriment of linear clarity. In the Allemande he conveyed the feeling of a formal dance by strutting sternly and tightly confining the notes of the phrases; his Burlesca was contrastingly forthright and bracing; whilst the Corrente came over as spry and spirited (‘unbuttoned’ sprang to mind). All in all, Stephen’s overriding priority apparently was to draw out but not exaggerate the inherent character of each movement – you might say he was ‘bending Bach without breaking Bach’s back’.

I was a bit surprised to find that, whilst the four Bach movements presented here were all on the quick side (of the seven movements of Bach’s BWV827 only one is slow), three of the responses were slow, even bordering on static. Leonie Holmes’s response to the Fantasia struck me as a deeply felt elegy, apparently based on charred fragments of the Bach – a rather grim something upon which to ponder. Chris Gendall’s Monolithe Allemand was curiously reminiscent of the fragmental, twitchy, ‘stop-go’ style that became the ‘in thing’ with the ‘squeaky gate’ school of around 60 years ago (and also, albeit in a slightly more lyrical form, by certain modern jazz pianists of the time). ‘Far out, man’ it may have been then, but I didn’t ‘dig’ it – and, with apologies to Chris Gendall, I must admit that I still don’t ‘dig’ it.

Even more curious was Juliet Palmer’s Burl. Its substance was one brief ‘twiddle’, repeated, varied, extended, counterposed; although its pitch changes seemed to imply a melody, this piece was more like Baroque ornamentation shorn of its music – homeless baubles in search of a Christmas tree. It left me feeling a bit like Hamlet’s Horatio; perhaps I should say, ‘Heavy, man’ and, with apologies to Juliet Palmer also, listen to it a few more times?

To my rescue came, in a manner most timely, Christopher Norton’s response to Bach’s Corrente. This reminded me of Saint-Saëns, when he was struggling to get his Second Piano Concerto off the ground, seeing Fauré’s latest student exercise and exclaiming, ‘Give it to me, I can make something of this!’. Norton grabbed the salient thematic nuggets, and gleefully transformed them into a piece of modern jazz, but decidedly of the red-hot variety – haring along, bristling with savage syncopations and dense left-hand chords, it was that rarest of birds, a borrowing from Bach that sounded not a bit like Bach! All four responses had one important point of commonality: Stephen’s nigh-on peerless, intensely focused advocacy, which to a large extent relieved my burden of bewilderment.

Stephen’s performances of the selection of four Debussy plums, presented in what looks like reverse chronological order of composition, were an unqualified delight – I suppose partly because his favourites included none of Debussy’s ‘blockbusters’. Taken very slowly, with carefully balanced chords and canny pedalling drawing out the reverberations with nary a hint of blurring, ‘Feuilles mortes’ had an involving sense of … what? It’s rare music that evokes an emotion that you can’t quite put your finger on; would ‘autumnal regret’ perhaps cover it? I have never heard the footsteps of ‘Des Pas sur la Neige’ more clearly evoked; like a ghostly aura the harmonies seemed to cling to them, whilst the fragments of melody mostly stood apart.

In ‘The Little Shepherd’ Stephen delicately differentiated the probing ‘verse’, sounding like a distant call, and the timid, skipping ‘refrain’ nearer at hand, creating a singularly wistful picture. Finally, ‘Clair de Lune’ was divested of its ‘warhorse’ status, its vacillating between obscure mystery and silvery brightness calling to mind passing clouds. Following an intensely passionate climax, Stephen’s finely judged rippling flow conjured a vivid sense of moonlight glinting off a babbling brook.

Even with the interval intervening, the contrast wrought by Fauré’s Nocturne No.4 was quite startling. Stephen let its simple charm tell its own tale, its lilting, full-blown melody, over a ‘standard’ accompaniment largely of chord-tones, easing its way, fantasia-like, from one ‘viewpoint’ to another, occasionally attaining a state of seemly passion. Stephen confessed that he regards this piece as ‘the most beautiful piano work’; I would go along with that, with the proviso that ‘a’ is substituted for ‘the’.

At this juncture, we heard the second of the two particularly intriguing items: an improvisation. Apparently, Stephen swears by improvisation as an excellent way of ‘keeping fit’, that is, exercising his musical wits. You may ask, ‘And how do we know that the ‘improvisation’ has not been carefully rendered note-perfect beforehand?’ I’ll tell you. Stephen produced a pack of playing cards, the face of each card being inscribed with the name of a note (presumably the deck contains 36 cards – three of each of the twelve notes). This he shuffled and fanned, before inviting a front-row audience member to ‘pick a card – any card’ three times over. These three notes became his ‘subject’. Now, unless he has the magician’s ability to ‘force’ the choice to an extraordinary, triple degree, his only way of cheating would be to prepare and memorise a vast number of ‘improvisations’. It’s not likely, is it?

The cards drawn were C-D-D! Elaborating, Stephen worked these notes into a rather nice melody, something of a Lisztian Liebestraum filled with passion and rippling left hand, before shifting to a livelier vein for a conclusion. Stephen, thinking that C-D-D was a bit too easy, had another go. This time the cards came up with, would you believe, FFE. These, also a bit too easy, he re-ordered to FEF, making of this a piece that rattled along like a Bach-cum-Liszt toccata – or perhaps a ‘racing’ tune. Good fun for all – but perhaps tinged by regret that we’ve so enjoyed two pieces that will never be heard again.

The final items were two contrasted bits of Chopin. In the Ballade No.3, Stephen was keenly alive to both nuances and larger shifts of mood. In particular he elucidated the textural qualities of certain phrases, especially the little ‘holding’ interludes which are often highly coloured; and ensuring that the dance rhythms really did dance. Needless to say, he wrapped his fingers confidently around the knottiest passages, which, truth to tell, are as nothing compared to those of his final item:

The Polonaise Op.53 ‘Heroic’ (possibly the supreme warhorse of the piano repertoire?) he delivered in the grand manner: bags of contrast, rubato, extremes of dynamics etc. In the central episode, Stephen took full advantage of the ostinato bass to generate overwhelmingly powerful crescendos. Sometimes this furiously festive attack resulted in the odd fluff. There is absolutely nothing wrong with that – in fact, quite the opposite: if there are no fluffs in a live performance of this piece, the player is signally failing in his prime duty, to ‘give it all he’s got’. And, as if to prove the point, Stephen’s sheer drive and ebullience won the day, and the audience’s wholehearted approbation.

Paul Serotsky