United Kingdom English National Ballet’s EK/Forsythe/Quagebeur: Dancers of English National Ballet, English National Ballet Philharmonic / Gavin Sutherland (conductor). Sadler’s Wells, London, 9.11.2022. (JO’D)

United Kingdom English National Ballet’s EK/Forsythe/Quagebeur: Dancers of English National Ballet, English National Ballet Philharmonic / Gavin Sutherland (conductor). Sadler’s Wells, London, 9.11.2022. (JO’D)

Blake Works I

Music – James Blake: Songs from The Colour in Anything

Choreography, Stage design, Costume design and Lighting design – William Forsythe

Stager – Ayman Harper

Lighting design – Tanja Rühl

Costume design – Dorothee Merg

Take Five Blues

Music – Nigel Kennedy, songs from Recital: Take Five (written by Paul Desmond); Vivace; Allegro; Dusk

Choreography and Costume design – Stina Quagebeur

Lighting design – Simon Bennison

The Rite of Spring

Music – Igor Stravinsky

Choreography – Mats Ek

Rehearsal director – Ana Laguna

Costume and Set design – Marie-Louise Ekman

Lighting design – Linus Fellbom

Featured Dancers – Erina Takahashi (Mother), James Streeter (Father), Emily Suzuki (Daughter), Fernando Carratalá Coloma (Bridegroom)

At the end of The Forsythe Evening in March this year (review click here), English National Ballet sent Sadler’s Wells audiences home on a note of joyous exuberance. For this new triple bill, it takes the bold decision to frame the joyous work, Stina Quagebeur’s Take Five Blues, between two of a more sombre nature: William Forsythe’s Blake Works I and Mats Ek’s The Rite of Spring. It is a decision that pays off.

The company’s Associate Choreographer, Stina Quagebeur has been creating work for its dancers since 2014, at least. The memory of Nancy Osbaldeston and Guilherme Menezes in the duet, Vera, at the Barbican that year, still lingers. Take Five Blues is on a larger scale. First shown online during the lockdown of 2020, it has been expanded for this new season. While not without moments of potential menace, ultimately it celebrates dance (to the sound of Nigel Kennedy’s lively violin) as competition, cooperation and play.

A former member of the company, who could bring unexpected pathos to the role of Grandmother in Wayne Eagling’s Nutcracker, Stina Quagebeur has a deep understanding of its dancers, both male and female. They show enjoyment, as dancers of ballet, in what they can do with their bodies (performing several tours chainés déboulés). They transmit that enjoyment to the audience. While the competition is not necessarily between the sexes, at the end a smiling Julia Conway, Katja Khaniukova and Angela Wood stand over their male colleagues, who have fallen to the floor as if exhausted.

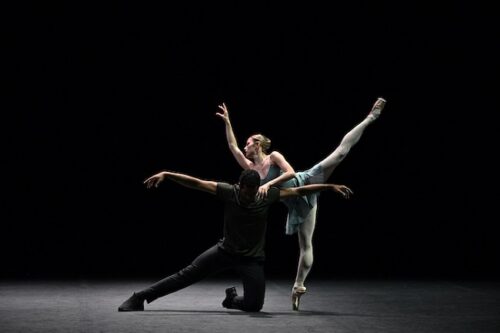

Blake Works I was part of The Forsythe Evening. Its melancholier aspects, then, must have been overshadowed by the ebullient Playlist (EP), that followed. On this bill, James Blake’s voice sounds more mournful. The duet that Emily Suzuki and Junor Souza perform to it looks more restless. One section of the piece closes on a perpetuum mobile as three men repeatedly rearrange the arms of their female partners, who repeatedly appear to resist. In the final pas de deux, the arms of Emma Hawes and Aitor Arrieta encircle emptiness. An echo perhaps of the circle that Eugene Onegin makes with his arms around Tatiana as he tries to regain her love at the end of John Cranko’s Onegin.

In Mats Ek’s The Rite of Spring the ‘rite’ is an arranged marriage like that planned for Juliet to Paris in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. It is a subject the choreographer previously touched upon in his own Juliet & Romeo. Erina Takahashi and James Streeter are the implacable Mother and Father, the dusty pink of whose silky but oddly stiff and loosely cut costumes (designed by the painter, Marie-Louise Ekman) are in stark contrast to their spiky, angular gestures of anger and pain.

Emily Suzuki, almost buried some of the time beneath a voluminous white wedding dress and veil, is the daughter who resists her fate. Fernando Carratalá Coloma, also in white, is the Bridegroom who seems willing, at one point, to help her. For doing so, both incur the anger of the ‘tribe’ (the women identically dressed versions of the Mother, the men of the Father). Making shapes with their arms that bring photographs of the original The Rite of Spring dancers to mind, using their dusty pink clothes to beat the recalcitrant Daughter, rolling across the stage: the dancers of English National Ballet, with the support of the English National Ballet Philharmonic under Gavin Sutherland, bring the piece not to a climax marked by death, but to the post-climactic question of ‘What now?’

John O’Dwyer