United Kingdom Britten: Prince of the Pagodas: Birmingham Royal Ballet, Royal Ballet Sinfonia / Koen Kessels (conductor), Birmingham Hippodrome, 26.2.2014

United Kingdom Britten: Prince of the Pagodas: Birmingham Royal Ballet, Royal Ballet Sinfonia / Koen Kessels (conductor), Birmingham Hippodrome, 26.2.2014

Photo: Bill Cooper

Cast:

Princess Belle Sakura: Yaoquian Shang

The Salamander Prince: Yasuo Atsuji

Empress Epine: Delia Mathews

The Emperor: Jonathan Payn

Court Fool: Lewis Turner

Court Official: Valentin Olovyannikov

Child Prince: Charles Heaman

Child Princess: Ceri Rigby

Little Salamander: Jake Tang

King of the North: Kit Holder

King of the East: William Bracewell

King of the West: James Barton

King of the South: Brandon Lawrence

Yokai: Tim Hill, Joshua Lee, Yujin Muraishi, Archie Sladen

Seahorses: Jonathan Caguioia, Max Maslen, Lachlan Monaghan, Luke Schaufuss

Deep-Sea Creatures: Feargus Campbell, Steven Monteith

Flames: Samara Downs, Yvette Knight, Callie Roberts, Yijing Zhang

Balinese Ladies: Ruth Brill, Laura Day, Karla Doorbar, Reina Fuchigami

Production

Choreography: David Bintley

Designs: Rae Smith

Lighting: Peter Teigen

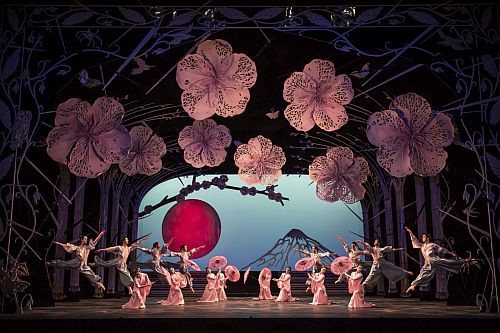

Britten’s The Prince of the Pagodas, now given – taken overall – a visually electrifying new production by the BRB’s Artistic Director David Bintley, is not really what you could call a neglected ballet. True, it enjoys none of the cachet of Britten’s operas, almost all staged often and worldwide; it has the degree of recognition of, say, Vaughan Williams’ Job. But if one looks at the postwar years, whence it stemmed, there is many an accomplished ballet score – Bliss’s Adam Zero, Rawsthorne’s Madame Chrysanthème, Lambert’s Romeo and Juliet, Williamson’s The Display and so on – still knocking on the door for attention.

Since John Cranko first staged it on New Year’s Day, 1957, Pagodas has seen enough productions, in the UK and abroad, to be now deemed a classic. The music for it reaches back almost to The Turn of the Screw (1954), but a greater part of the inspiration came from Britten and Pears’ fortnight-long holiday in Bali in 1956, which reinforced an interest the composer had in oriental, and particularly Balinese, music. Four of the most enticing dancers in David Bintley’s new production for Birmingham Royal Ballet are indeed cast as Balinese maidens.

This is a production that wins on nearly every count, with for the most part scintillating choreography by Bintley, and a series of dancers (two or three casts are involved) who delight the eye with their personal flair and eloquent invention. Britten’s ballet is supposed to have its longueurs – practical problems that (as Bintley himself points out) didn’t help Kenneth MacMillan’s production in 1989. Happily I found none here.

Let’s start with some less obvious successes. The Emperor (Jonathan Payn) is an ailing, decrepit halfwit, who charms us less by his mobility than by the fact that for part of Act II he is seated on a fabulously, economically designed replica of Mount Fuji. Everything about Rae Smith’s décor thrills: its orientalism, its exotic ideas, unexpected touches, its aptness; this pliant, subtly tweaked, sensitive set, splendidly handled, pinpoint accuracy, by the BRB stage crew, is never less than beguiling. Yet near the end the ruler is suddenly rejuvenated, and by his patient Court Jester is helped frontstage to perform an extraordinarily witty, dinky, compacted little trepak-like foot dance. One of the least noticeable moments, it was for me one of the most poignant and attractive.

The Jester or Fool – parallels with King Lear are often drawn, but Bintley and young dancer Lewis Turner give him a wholly original, attractive character, orientalised but not overdone, cheeky but deferential, and extraordinarily sympathetic. It’s Turner who begins the show, with a (not particularly effective) piece of front-of-curtain comic clowning. But once he dances – for me, he doesn’t have enough – he is a delight to the eye: elegant, articulate, loyal, eminently huggable.

There are three child dancers, too, who add a piquant touch to the story – young Prince shockingly transformed into a salamander by (here) wicked usurping stepmother: the young teen trio graphically conjure up the past and beautifully re-enact the original transformation. Ceri Rigby’ girl princess and Charles Heaman’s boy prince and princess are a joy briefly to behold.

Although never by the music under BRB’s Belgian Music Director, Koen Kessels, there were actually times when one was underwhelmed by the dance. The pirouettes by four wooing princes, from North, South, East and West, looked elegant and apt (a Slavic gopak, hot pursued by an oriental dance with cymbales) felt marginally thin and pedestrian compared with the exotic beauty they were seeking to appeal to; they are slightly better in their later reappearance en masse.

Four Seahorses – while quite clever and deft and a visual treat, beautifully outfitted by Rae Smith, whose costumes are likewise a marvel – are less artfully coordinated than their brilliantly choreographed deep-sea near neighbours, a delightful comic duo (Feargus Campbell, Steven Monteith) who bring archness if not campness (and consequent hilarity) to their moves and provide frankly a miracle of precision. Often a treat to watch is the wicked Empress, Épine (Delia Mathews), whose purple attire seems to dance in perfect harness with her stylishly exaggerated gestures, even where again invention and characterisation seems cardboard compared with the creepy psychological shiftings of the set.

Everything young Yaoqian Shang (the Princess) touches seems to turn to gold. She has more joints in her body, and more ways of coordinating or sequencing their movement, than anyone else onstage. Whereas Yasuo Atsuji’s Salamander Prince – her brother – excels more in his black and white snaky form than in human shape, Shang is never for a second dull to watch. Her delicacy, her poise on point, her easy dexterity off point, her angles of drooped shoulder or trailing forearm, as well as knee and ankle, coupled with her natural grace and look, render her a bright beacon every moment she is onstage. She hits nerves others don’t.

Another delight is the BRB’s ensemble dances: occasionally corny, but also well-delivered, personable, beguiling. They contrast elegantly with the deliciously un-elegant moves of the Yokai (Tim Hill, Joshua Lee, Yujin Muraishi, Archie Sladen), strange supernatural apparitions, chubby staring-eyed monsters who are, happily, on the side of the good.

Britten’s score, for all its thumping triads, for me, scarcely wearies at all – not just his coherence and endless creativity tell, but the way he produces such scope and variety from the instrumentation. Kessels’ team produced sensationally good trumpet solos (blasts of full offstage trumpets from above the audience are a highlight of the later stages), wheezing woodwind, mysterious upper string tone, and some alluring glissandi for the Salamander.

There is much more from a scrupulously attentive, sectionally alert Royal Ballet Sinfonia: scampering marine-evocative alternations between clarinet and bassoon; whining saxophone at poignant key moments; cor anglais for the little girl princess, two appetising flutes for the Empress’s twilight cavortings; exquisite harp detail; and lovely collective and individual touches to supplement the oriental (Balinese) girls’ dancing.

No surprise at all that when the Sinfonia’s beautifully poised percussionists mimic the sound – quite late on – of the Indonesian gamelan, especially when brilliantly pared down to just flute and keyboard for accompaniment, one should sense a foretaste of Curlew River and the Church Parables. The moment of transformation was thrillingly conceived; the almost superfluous final triumphal dances not.

Roderic Dunnett