United Kingdom Vincenzo Lamagna (after Adolphe Adam), Giselle: Soloists & Artists of English National Ballet with English National Ballet Philharmonic / Gavin Sutherland (conductor). Sadler’s Wells, London, 15.11.2016. (JPr)

United Kingdom Vincenzo Lamagna (after Adolphe Adam), Giselle: Soloists & Artists of English National Ballet with English National Ballet Philharmonic / Gavin Sutherland (conductor). Sadler’s Wells, London, 15.11.2016. (JPr)

Cast:

Giselle – Tamara Rojo

Albrecht – James Streeter

Hilarion – Cesar Corrales

Myrtha – Stina Quagebeur

Bathilde – Begoña Cao

Landlord – Fabian Remair

Production:

Direction and Choreography – Akram Kham

Visual Design and Costumes – Tim Yip

Lighting Design – Mark Henderson

Dramaturgy – Ruth Little

Akram Khan’s new ‘take’ on Giselle finally reached London after its Manchester premiere and a short UK tour: I had avoided reading too much about it, though was well aware of the ‘buzz’ it has generated. This week at Sadler’s Wells quickly sold out and probably so will the further run of performances next year.

This is Akram Khan’s first full-length ballet. His background is Indian kathak and contemporary dance and he would not be the first choreographer to come to mind for creating a new Giselle, ‘traditionally’ the epitome of Romanticism. Of course Khan has worked very successfully with Sylvie Guillem and previously with English National Ballet in 2014 on Dust, part of the company’s Lest We Forget programme (review). I wrote then how that work was ‘something that I certainly want to see – and hear – again because it was so haunting, dramatic and, yes, actually quite agonising to watch. It revelled in the power of dance to display raw emotion and make a genuine audience connection with a powerful theme’ and, for me, Akram Khan’s Giselle was exactly the same. But it really has little to do with the nineteenth-century ballet (which ENB will dance at the London Coliseum in January 2017) and – to my hearing – there is not much of Adolphe Adam’s original score left in the expressively cinematic music from Vincenzo Lamagna who was a latecomer to the project.

The ‘original’ two-act ballet was premièred in 1841 in Paris and first staged in England the following year before shortly thereafter being presented by almost every ballet company in the world, having been recognised as an exceptional ballet. Although it has gained a few choreographic accretions along the way the original choreography of Jean Coralli, Jules Perrot and Marius Petipa remains often largely intact to this day and it is set to Adam’s familiar music. In comparison to some of the other story ballets, Giselle has greater psychological depths and explores the myriad themes of social class, love, betrayal, despair, forgiveness and redemption. Act I is an idyllic vision of peasant life, it is harvest time in medieval Rhineland village; the peasant girl, Giselle, has won the heart of the noble-born Albrecht, who disguises himself and lives among the villagers. Then Act II is inspired by a passage in Heinrich Heine’s On Germany, about Wilis or ‘young brides-to-be who die before their wedding day. The poor creatures cannot rest peacefully in their graves’ and rise at midnight to dance beguilingly in the moonlight.

The dramaturge, Ruth Little, writes how – together with Akram Khan – they took ‘the narrative structure of the nineteenth-century … and adapt it to the circumstances of a community of migrant workers (“the peasants” of the original version) … The impulse to renew the story of Giselle is rooted in the precarious situation of migrants and refugees everywhere today’ concluding how this Giselle ‘is a work of rituals and cycles, suffused with the memory of movement, the violence of inequality, and the resilience, capability and desires of the human body.’

There is a narrative here but unfortunately what is shown is mostly impressionistic and relies on the audience’s understanding of the Giselle story to make any connection with 1841. Hopefully Khan might revise some of it before next year because, yes, I understand Giselle and all around her are now migrant factory workers (the Outcasts) rather than happy peasants; and how Albrecht might be one of the wealthy ‘landlords’ (who only appear outlandishly dressed late in Act I) yet pretends to be a migrant. The local garment factory has been shut causing the migration of those seeking work elsewhere. When the ballet starts it is initially difficult to spot who is who. Usually, Albrecht’s class duplicity is made clear from the outset, but here it is only apparent as Act I draws to a close. Hilarion seems not to know what he wants and is torn between the two worlds of privilege and poverty, though he is clearly infatuated with Giselle. Khan creates a great sense of community, but the storytelling is weak and it is up to each individual watching to determine how important that is for you. It is not entirely clear how the pregnant Giselle dies after Hilarion’s revelation, even though there is a haunting image of her almost drowning in her despair amongst the linking and writhing arms of her compatriots.

Before looking at how this new Giselle ends it is important to mention its most topical visual aspect and that is the stage wide Wall from Tim Yip who is also responsible for the costumes. It can menacingly rotate but primarily separates the ‘haves’ from the ‘have nots’. This can be seen in Khan and Little’s context of a mass human movement from rural areas to cities, or from impoverished areas to more prosperous ones; though any mention of a wall now brings President-elect Donald Trump immediately to mind. The community push at it as the ballet starts and Albrecht will try this himself at the very end before breaching it to become an Outcast himself.

In Act II the Wilis are now the ghosts of the factory workers who Ruth Little writes ‘have laboured, and too many died’ and they carry bamboo canes as weapons to wreak vengeance on men. It is suggested these ‘refer to the structure of the hand loom and early weaving machines’ which were superseded by mechanisation, the sounds of which haunt Lamagna’s new score. (It is not Akram Khan’s fault that I am currently reading the autobiography of Dick Van Dyke and this reminded me too much of ‘Me Ol’ Bamboo’ from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang!) Hilarion meets a violent end whilst Albrecht – who gets his own solo of abject and true remorse at the start of Act II – escapes the Wilis’ retribution having learnt the error of his ways. Up to that point there is a numbing sense of dread and foreboding during this act which is visceral and gripping.

Vincenzo Lamagna’s amplified orchestral music with added – mostly electronic – sound effects is an honourable pastiche of the marvellous film scores of his fellow countryman, Ennio Morricone and there are only the most fleeting references to Adolphe Adam. Certainly because of the additional vocal elements there was something in Act I – for what must be Akram Khan’s representation of a boisterous folk dance – which could have come straight out of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. It is all played with the usual supreme virtuosity by the English National Ballet Philharmonic under Gavin Sutherland.

Akram Khan has developed a movement language which is clearly uniquely his own; there is the hand movement of kathak fused to a restless physicality that has moments of balletic virtuosity and lyrical mobility, especially when it alludes discreetly to the original choreography. Setting aside my doubts about the narrative, this Giselle is a triumph for English National Ballet who are laying strong claims to becoming London’s most innovative and technically accomplished dance company.

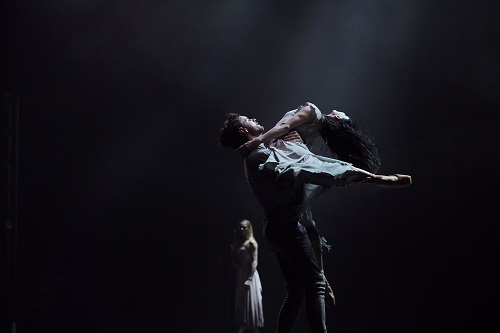

Nothing I have seen recently – albeit mostly at the cinema – from The Royal Ballet comes close to English National Ballet’s recent achievements. The company dance what they were given magnificently, led by their wonderful artistic director, Tamara Rojo, as Giselle. I hope she will forgive me for reminding readers that she is now of an age when The Royal Ballet pension off their ballerinas. Rojo is still at her peak of her powers, fully inhabiting the choreography and genuinely embodying all Giselle’s heartache and unhappiness to bring the character to real life. She was strongly partnered by James Streeter – it may be my imagination but he looks sleeker than of late – and any lack of characterisation from him is possibly Khan’s fault, though he managed to bring some true emotion to his duets with Giselle. Cesar Corrales gets better and better and eyes are drawn to him when he moves. Hilarion’s motivations are never entirely clear but it doesn’t seem to matter even when – on his reappearance in Act II – it looks as if he rapes and kills Giselle who I thought was already dead anyway. Finally, Tamara Rojo has unearthed – almost literally in his case – another potential new star from ENB’s ranks in Stina Quagebeur’s Myrtha; she is remarkably good as a spectral and zombie-like figure who – especially because she is en pointe as all the Wilis are – haunts Act II authoritatively.

Jim Pritchard

For more about English National Ballet’s forthcoming performances visit http://www.ballet.org.uk/.