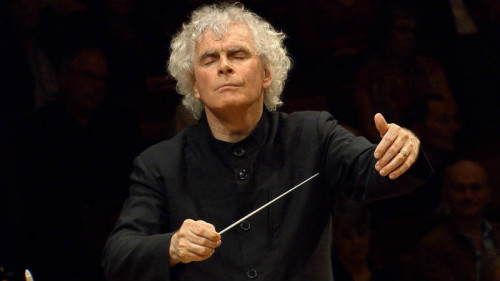

United Kingdom Bartók and Bruckner: London Symphony Orchestra / Sir Simon Rattle (conductor), Barbican Hall, Barbican Centre, London, 20.1.2019. (AS)

United Kingdom Bartók and Bruckner: London Symphony Orchestra / Sir Simon Rattle (conductor), Barbican Hall, Barbican Centre, London, 20.1.2019. (AS)

Bartók – Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste, Sz.106

Bruckner – Symphony No.6 in A (Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs Urtext Edition)

After the first London performance of this programme on 13 January, Rattle and the LSO played it on four consecutive evenings in Budapest, Warsaw, Wrocław and Kracow. If conductor and orchestra were given a two-day break from it before the sixth performance on 20 January, they certainly earned it.

Travel difficulties caused me to miss the Bartók work at the first London perfromance, so I was grateful for the chance to hear it at the second one. There was absolutely no trace of staleness or fatigue in a quite wonderful presentation of this score. Though it is one of Bartók’s finest works, it is very approachable on account of its folksong elements, its pungent rhythms and of course the intriguing sounds produced by the unusual combination of instruments and the division of the strings into two antiphonal groups. In bringing out all of these unique characteristics Rattle was entirely successful, as he was in projecting the slow mysterious fugue of the first movement, which builds to an astringent climax, also the bouncy rhythms of the second Allegro, the sinister nocturnal mood of the Adagio, and the bursting energy of the final Allegro molto. And it wasn’t just colour and energy that Rattle found in the score, for he unerringly found and pointed the sophisticated accents in which it abounds: and he strongly and effectively brought out the authentic nature of Bartók’s rhythms, which are tautly held together but which also seem, paradoxically, to have a free spirit. We might have been listening to a performance by one of the great Hungarian conductors of the past – Ferenc Fricsay or Fritz Reiner, for instance. The LSO’s playing was dazzlingly virtuosic.

The version of the Bruckner symphony that Rattle conducted was that named above in the titling. Stephen Johnson’s programme note explained that after the work’s composition Bruckner ‘made adjustments to articulation markings and in places clarified textures, which are here included for the first time in a published score. The changes may be subtle, but they bring us closer to what Bruckner actually had in mind when he conceived this fascinatingly, remarkable original symphony’. But wait a minute. An Urtext is by definition an original. So, if Cohrs has included Bruckner’s adjustments, however minor, then his edition is not Urtext. And if Bruckner made changes to the score, they took it further away from his original thoughts, not closer to them. In the event, no knowledgeable listener I consulted after either London performance had detected any aural changes in the music.

Both London performances, though played at either end of a series of six, were remarkably consistent, and movement timings were very similar. There may have been, understandably, a very slight loss of spontaneity in the second, but both showed the very high standard of playing one expects of this orchestra, and Rattle’s conducting was unfailingly electric and highly communicative throughout. He maintained a strong, driving pulse throughout the first movement, dovetailing its various components with great skill. There was complete clarity and the sense, as there should be, of an overriding, linking arch. The Adagio flowed beautifully, with some lovely playing from the LSO strings, and the movement’s long-breathed melodies were somehow invested with a very touching quality of repose and dignity. The tempi for the Scherzo and Trios were very well calculated, and as in the first movement Rattle held the diverse content of the Finale together very successfully. His basic tempo was quite brisk, but it didn’t seem too hurried. Overall it was quite a ‘modern’ performance, without the expansive speeds and expressive lingerings of the old-school Bruckner conductors. Perhaps great music such as this can take different kinds of approach, each of them valid, provided that the basic elements of the score are faithfully protected.

Listeners to the second concert were rewarded with an encore, a Polish dance from Moniuszko’s opera Halka, which had been played as an extra to appreciative audiences on tour as a two-hundredth centenary tribute to the composer’s birth in 1819.

Alan Sanders

Apparently Mr. Sanders has not a clear idea what scholars call an “urtext edition” these days, namely, an edition which discusses all relevant sources of a work and presents a text in which this dicussion is outlined by the editorial approach – and not an “original”. Mr. Sanders seems to use the word “urtext” merely referring to the autograph score as it is, with a minimum of editorial addenda. The sad result can be seen in the editions of Haas and Nowak, with “editorial reports” merely describing the sources instead of justifying the editorial work in a detailed commentary, and quite some errors. The new edition by Dr. Cohrs presents, on the contrary, not only a detailled commentary, but also the results of his research and editing in a score using multiple colours for addenda as well as the sources he used.

Regarding the interpretation, the first movement’s “Maestoso” has a pencilled metronome marking of minims = 72 in the autograph score – much more vivid than the 54-60 usually to be heard, and the initial theme has to be faster than the other themes, which are a third slower in proportion. (By the way: Roger Norrington had realised this in performance and on disc already 20 years ago.)

The overcome interpretation models from old-school Bruckner priests Mr. Sanders may favor, but for unbiased musicians, the business-as-usual-interpretation of this movement appears like taking the first movement of Mendelssohn’s “Italian” on half speed. And if London listeners like Mr. Sanders heard “no aural changes in the music”, they rather don’t know the score/piece well enough ……

[edited]

Forwarded from Alan Sanders.

In the first place it seems a shame that Hipster feels the need to hide behind a pseudonym. Come out, Hipster, and tell us who you are! In fact the email address suggests a German server, so that gives us an identification clue, maybe.

Collins German dictionary defines Urtext as ‘original’, and that’s what it is. It has no new meaning.

Did my review express a preference for what I described as ‘the expansive speeds and expressing lingerings of the old-school conductors’, as Hipster says I did? No, it didn’t. It takes all sorts to make a world, but I rated Rattle’s performance very highly in my review, as anybody who reads it can see.

If the changes that Cohrs has made are ‘subtle’, maybe they are too subtle for the poor London listeners who lack musical knowledge and were without scores to pick them up, as Hipster contemptuously suggests. In Germany it is no doubt different! But this provokes one further thought. Do such admittedly minor and seemingly inaudible changes justify the presentation of the original score with the Cohrs revisions as a new edition?

I live indeed in Berlin. And no, I am not him. I would only recommend before critizing a new Urtext edition as the one of the Sixth by Cohrs with words so harsh, one should perhaps at first order his score and risk a closer look into the editorial approach of the new Anton Bruckner Urtext Gesamtausgabe.

It may speak for itself that conductors like Simon Rattle and Daniel Harding champion these editions, and perhaps for some good reason?

Maybe Mr. Sanders has a different view on what an urtext edition should be; he may also dislike the scholarly work of Dr. Cohrs, or even the man himself, but Collins’ Dictionary is certainly not the holy bible, nor the reference to what modern editorial music practice regards to be an Urtext Edition today — of which the first standards were set by publishers like Bärenreiter already 30 years ago (think of, e.g., Jonathan Del Mar’s Beethoven Urtext Editions).

Cohrs has edited, so far, Symphonies 5, 6, 7, Missa Solemnis in B flat and the Requiem. At the moment there are only the rental scores and parts, but as far as I have heard the first Study Scores are to be expected this or next year. However, Mr. Sanders could do the same easy thing I did regarding N° 6: Order a press copy from Schott Music. he may even like to review it?

If Mr. Sanders is capable of reading scores he may hopefully find some interesting information and insight in these new editions.

[edited comment]