United States Angelin Preljocaj, Les Nuits (The Nights), Ballet Preljocaj, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 20.6.14-22.6.14 (JRo)

United States Angelin Preljocaj, Les Nuits (The Nights), Ballet Preljocaj, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 20.6.14-22.6.14 (JRo)

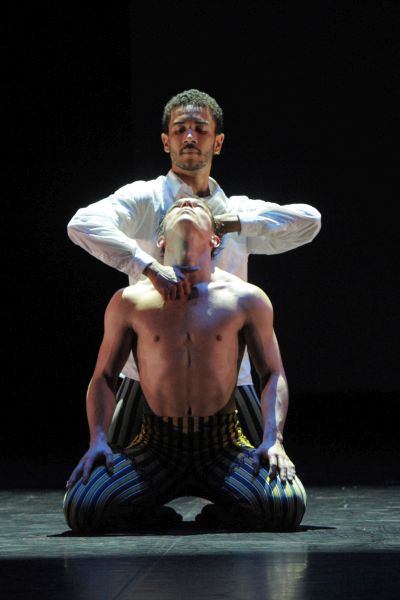

Photo Jean-Claude Carbonne

Dancers:

Margaux Coucharrière, Léa De Natale, Caroline Jaubert, Émilie Lalande, Céline Marié, Aude Miyagi, Nuriya Nagimova, Anaïs Pensé, Wilma Puentes Linares, Nagisa Shirai, Anna Tatarova, Cecilia Torres Morillo, Sergi Amoros Aparicio, Aurélien Charrier, Marius Delcourt, Jean-Charles Jousni, Fran Sanchez, Julien Thibault

Production :

Choreography: Angelin Preljocaj

Music: Natacha Atlas & Samy Bishai, 79D

Costumes: Azzedine Alaïa

Set Design: Constance Guisset

Lighting: Cécile Giovansili-Vissière

Les Nuits, by Angelin Preljocaj, inspired by One Thousand and One Nights, is a magic carpet ride of a ballet, flying to an imaginative realm where myth and psyche meet. On the surface it’s a marvelous entertainment, but beneath the pure pleasure of the ballet, is an exploration of woman’s role in society, our cultural prejudices, and what constitutes sexual intimacy.

With a cast of eighteen uniquely talented dancers, Preljocaj (pronounced prel-YO-tsa in Albanian and prel-zho-KAHJ in France where the company resides) manages to create movement that feels organic to his subject matter, suggesting the fantasy East of the Western colonialist’s mind without condescension or cliché. He is treading on dangerous territory here, but he manages to offer sly and subtle commentary, while providing seductive treats galore. The result is bewitching.

The poetic atmosphere is enhanced by the moody lighting of Cécile Giovansili-Vissière. In fact, Preljocaj is adept at choosing all of his collaborators. The Minimalist sets suggestive of Arabic arches and onion domes by Constance Guisset, and the modernist costumes of fashion designer Azzedine Alaïa create a harmonious whole, adding a seductiveness to Les Nuits without overstatement or glitz. Similar to Diaghilev, who created collaborations with contemporary artists for the Ballets Russes, Preljocaj’s surrounds himself with artists of his day. The lavishness of Leon Bakst’s famed set and costume designs for Fokine’s Scheherazade, however, is a far remove from the simplicity of Les Nuits.

The original music of Natacha Atlas and Samy Bishai is also at a remove from Rimsky-Korsakov’s lush melodies. Instead we have a potpourri of Western and Eastern music including electronic beats, popular song, dripping water, chirping birds, hypnotic chants, and Arabic instrumentations. Though musical transitions from dance to dance are abrupt at times, the overall impression is hypnotic and satisfying.

Drawn mainly from Persian and Indian folklore and literature, One Thousand and One Nights centers on the character of Scheherazade as she weaves tales to entertain the king and keep herself alive from one dawn to the next. Sinbad, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and Aladdin are familiar to generations of children; but the unexpurgated tales have their dark and erotic side. It is the sensuality of the stories that intrigue Preljocaj, so leave the little ones at home.

The sensuality strikes the moment the ballet begins. Reclining on the floor, turbaned and draped in white, ten women, bathed in dappled light and rising vapors, sway languorously. We are in a suggestion of a harem with all the potency of Ingres’ painting, The Turkish Bath. Odalisques from every period of art come to mind – Jacques-Louis David, Edouard Manet, and Pablo Picasso to name but a few. There is more at work here than mere eroticism, however: the dancers move in defined patterns, slowly coalescing into two groups, creating a kaleidoscopic arrangement. Structure and form are everywhere, testifying to the true artistic capabilities of the choreographer. No matter how intense the sexual atmosphere or free the dancing, Preljocaj organizes space with the eye of a painter composing a canvas, while movements are carved with the precision of a sculptor. Languid arms, throbbing torsos, and pliant legs all serve his artistic vision, never veering into extremes or unfolding for the sake of originality alone.

There is so much to intrigue one here that I will list just a few of the many stunning dances in the piece: Insect-like sexual coupling, which speaks of human behavior; a chorus line of women who move in super-model like posturings before breaking out into gestures of domination and anger; three pairs of men – one man of each pair “shaving” the other (is it grooming or does it refer to torture?); four carpets held aloft and in front of sixteen dancers whose legs and feet are the only body parts visible (deliciously funny); a demented picnic of twittering limbs and torsos on the four fallen carpets; a pas de deux reminiscent of an Indian miniature painting of Rajasthan; a rift on the Orientalism of the James Bond movies; the highly charged eroticism of women dancing on large urns into which they finally descend (this isn’t your Arabian Coffee movement from Nutcracker anymore); and finally, a dance set behind screens of filigreed bars conjuring Javanese shadow puppets.

The only false note for me was a hookah-smoking dance near the end of the hour and a half – it was the first time I felt cliché intruding on the piece. Beautiful though it was, my attention flagged, and I felt ready for the closing movement. But whatever its minor shortcomings, Les Nuits weaves a narrative spell that carries us along to the end of the ballet when dawn breaks and Scheherazade, still alive, lives to tell another fabulous tale of man’s foibles and desires.

Jane Rosenberg