Kern, Show Boat: Soloists, orchestra and chorus of San Francisco Opera, John DeMain (conductor), War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco. 1.6.2014 (HS)

Cast:

Magnolia Hawks: Heidi Stober

Gaylord Ravenal: Michael Todd Simpson

Cap’s Andy Hawks: Bill Irwin

Julie Laverne: Patricia Racette

Queenie: Anglea Renée Simpson

Joe: Morris Robinson

Parthy Ann Hawks: Harriet Harris

Ellie May Chipley: Kirsten Wyatt

Frank Schultz: John Bolton

Production:

Chorus director: Ian Robertson

Director: Francesca Zambello

Set design: Peter Davison

Costume design: Paul Tazewell

Lighting design: Mark McCullough

Sound design: Tod Nixon

Choreography: Michele Lynch

Although opera companies often seem defensive about presenting works written for the musical theater, Sunday’s first performance at San Francisco Opera of Show Boat, by composer Jerome Kern and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II,demonstrated magnificently that the music benefits from operatic singers, a full orchestra and serious production values. Besides, weren’t Mozart’s “singspiels” like Magic Flute written for bawdy night club-like environments? Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess is an opera that had to be written for a Broadway theater. Certainly the audience reaction—a prolonged standing ovation—showed no hint of condescension.

This go-round, a co-production with Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera and Chicago Lyric Opera (where it had its debut in 2012), went back to Kern’s original 1927 orchestration plus a few numbers Robert Russell Bennett re-scored for the 1946 Broadway revival. It also interpolated some material than Kern and Hammerstein included in subsequent productions, including the song “Bill” (which was dropped from an earlier musical by Kern (with lyrics by P.G. Wodehouse), two songs written by others, and John Philip Sousa’s “Washington Post March.”

These decisions combine to create an epic work on a grand scale, which is what Kern and Hammerstein had in mind when they wrote it (based on a popular novel by Edna Ferber) for Florenz Ziegfield to present in his brand-new theater. It turned out to be ground-breaking, the first successful attempt to meld the early Broadway musical—with its frivolous plots and dance hall roots—and operetta, with its richer musical forms and more expressive emotional content. This was a musical that had something to say.

At heart it’s a classic backstage romance. The revelation that Miss Julie, the boozy leading lady of the boat’s show cast, is of mixed race starts the plot in motion by opening up the leading roles for Cap’n Andy’s daughter, the starstruck Miss Magnolia, to play opposite Gaylord Ravenal, a dandy recruited at the last minute. They fall in love, of course, and the plot follows the course of their troubled future to Chicago and New York. Longtime opera director Francesca Zambello got it all to play with a deft hand against vivid candy-cane sets.

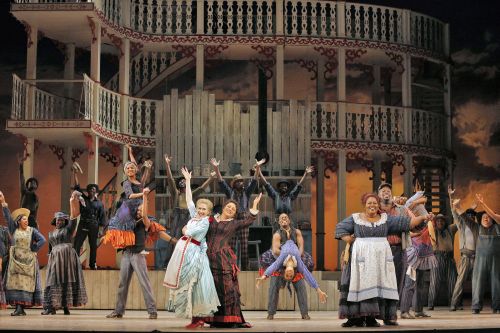

This story gains some depth from depictions of the overt racial issues that plagued America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, not just miscegenation laws but the general way people of color were treated. More African-Americans populate the San Francisco Opera stage in this performance than anything since Porgy and Bess, with separate black and white choruses and dance sextets (both excellent).

And, truth to tell, the most resplendent and powerful voices on stage belonged to the two prime African-American singers. Bass Morris Robinson deployed a finely honed, robust and deeply grounded sound in his dignified and beautifully centered portrayal of Joe. Robinson, who has appeared in all of the previous mountings of this production, makes “Ol’ Man River” into a personal symphony. As Queenie, his wife, the accomplished operatic soprano Angela Renée Simpson delivered her funny lines with a crackling sense of humor while singing the music with astonishing richness and pointed phrasing. She gets the serious side of the plot started with “Mis’ry’s Comin’ Aroun'” in Act I. “Queenie’s Ballyhoo” in the same act, in which she shows ’em how to bring in the crowds, and her Charleston-like song-and-dance in Act II, “Hey Fella” (which was cut from the original show) were both crowd pleasers.

These two hardly needed amplification, which sound designer Tod Nixon used to balance the voices with the full orchestra in an opera house double the size of the Broadway theater for which this was written. The audio enhancement also made dialog intelligible with minimal theatrical shouting. Musical balances were generally good and the sound warm, although the opening performance suggested that it can use some tweaking to make it less intrusive.

The amplification often allowed the rest of the cast to be more subtly expressive. As Julie, for example, soprano Patricia Racette (who is also starring in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly this month, presumably unamplified) could wring every last nuance out of “Bill” (“He’s just my Bill, an ordinary guy”) in a second-act showstopper. This was even better than “Can’t Help Loving Dat Man,” her first-act solo, which evolves into a recurring production number. Racette’s recent self-described “detours” into cabaret pay huge dividends in her utterly natural approach to these songs, allowing her expansive operatic voice to take over only in climaxes.

The other compelling star in this show is Bill Irwin. The Tony Award-winning actor, who has roots in Northern California—first as a clown in the locally popular Pickle Family Circus and later in such works as “Fool Moon” with American Conservatory Theater—put his rubbery body to work as an utterly captivating Cap’n Andy, who can’t walk across the stage without doing a nimble dance. The character runs the title river craft like a slightly daft theatrical impresario, despite his harpy wife. But he can also take charge. When the show within the show goes awry in Act I, he acts out the rest of the story with a brilliant comic turn that keeps the stage audience enthralled and the bigger audience in stitches.

In the plot Cap’n Andy also goes around his wife to help Magnolia (soprano Heidi Stober) marry her riverboat gambler suitor, Gaylord Ravenal (baritone Michael Todd Simpson). As the centerpieces of the story, Stober and Simpson acquit themselves well. Surrounded as they are by such star turns, however, they don’t really stand out as much as they might. Simpson’s reedy baritone has the necessary suavity to make him a believable rake, but the voice lacks the swagger in his dashing appearance. Stober’s light, creamy sound and wholesome looks work better, especially when the latent operatic power in her voice comes through as the character grows in maturity and stature over the 40-year arc of the story. Cap’n Andy shows up at an opportune moment in Act II to remind her how to win over a crowd, and the difference in her performance is palpable.

Their musical highlights include the tentative wooing duet “Make Believe,” and their ravishing love duet “You Are Love,” both in Act I, but when they are called upon to carry the show extensively in Act II their restrained approach to acting serve them less well. Still, they provide the glue that held the story together, allowing others to set off sparks. With their musical comedy experience, perky Kirsten Wyatt as Ellie Mae Chipley and John Bolton as Frank Schultz made a fizzy pair for the ragtime song-and-dance number “Good Bye My Lady Love” in Act II. Other Broadway veterans include Harriet Harris, who has made a career of playing harridans such as Parthy Ann Hawks (Cap’n Andy’s wife), and she does so here to great comedic effect.

The final scene, back on the riverboat, wraps up the story perfunctorily after a second act mostly set in Chicago, taking us out on a reprise of “Ol’ Man River” and the magnificent rumble of Robinson’s voice. Fortunately, this cast is being captured live for a Blu-Ray DVD and CD. Kern and Hammerstein knew they had a hit with that one, and so does San Francisco Opera.

Harvey Steiman