United States Matthew Aucoin, Crossing: 2017 New Wave Festival – Soloists, Chorus, A Far Cry/Matthew Aucoin (conductor), Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn, 8.10.2017. (RP)

United States Matthew Aucoin, Crossing: 2017 New Wave Festival – Soloists, Chorus, A Far Cry/Matthew Aucoin (conductor), Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn, 8.10.2017. (RP)

Cast:

Walt Whitman – Rod Gilfry

John Wormley – Alexander Lewis

Freddie Stowers – Davóne Tines

Messenger – Jennifer Zetlan

Ensemble – Hadleigh Adams, Sean Christensen, William Goforth, Frank Kelley, Michael Kelly, Ben Lowe, Matthew Patrick Morris, Daniel Neer, James Onstad, Jorell Williams, Gregory Zavracky

Dancers – Christina Dooling, Jehbreal Jackson, Jeff Sykes, Karell Williams

Production: American Repertory Theater in association with Music-Theatre Group

Director – Diane Paulus

Set Design – Tom Pye

Costume Design – David Zinn

Lighting – Jennifer Tipton

Production Design – Finn Ross

Sound Design – Sam Lerner

Choreography – Jill Johnson

Some of the press prior to the run of Matthew Aucoin’s Crossing at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) focused on the opera being particularly relevant at a time when the American Civil War reverberates so in our country. That is all fine and good, but in the end it is really just a love story. The hype could have as easily been over one man’s transcendent love for humanity and his efforts to ease the pain of those who have suffered mentally and physically in battle, a topic as relevant today as it was then. Aucoin, who wrote both the libretto and music for Crossing, created a work of art that has the potential to unite, not divide, if we would just let it.

The man is Walt Whitman, who drew upon all things American, including its religious heritage, to create poetry that symbolized a nation and to unify a country that bore the battle scars of a terrible civil war. Aucoin’s fictionalized account of Whitman’s time in Washington caring for wounded soldiers resonates with religious overtones. His Whitman embodies Jesus’ words, ‘Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me’. That Aucoin’s Whitman yielded to the temptations of the flesh make him human instead of a saint. That he was instantly remorseful of his transgression, begged forgiveness and, when rebuked, bore the man no ill will, are traits seldom seen in today’s world.

Aucoin (b. 1990), an American composer, conductor, writer and pianist, is currently Artist in Residence at Los Angeles Opera. This opera, which premiered in 2015 at the American Repertory Theater (ART) in Boston, was commissioned as part of the National Civil War Project, a multi-year, multi-city endeavor in commemoration of the war’s 150th anniversary. BAM basically imported the ART production lock, stock and barrel for its New York premiere.

The action takes place in a hospital ward crowded with iron beds. The only decorations are a portrait of President Abraham Lincoln and a US flag. The opening and closing backdrops are passages in Whitman’s handwriting, complete with edits. Projections are used sparingly but effectively to depict the rush of the tides in the East River, blue skies with billowing clouds, a sunset and the shells of burned buildings. The patients all have haunted faces and shattered bodies, including a double amputee in a wheel chair. There was no glossing over the horrors of war.

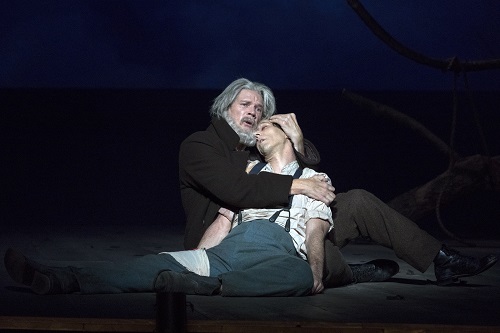

Rod Gilfry, with a full beard, long graying hair and a brown overcoat, was the embodiment of the proud, massive, handsome poet, whom some contemporaries called a ‘modern Christ’. Vocally he was rock solid, his baritone resonant and full, his voice perhaps like one of many that Whitman might have heard in his mind when he penned ‘I Hear America Singing’.

The average Confederate soldier was a young man in his early twenties, unshaven, unkempt, gaunt and hardened from months of difficult living. John Wormley was such a soldier, but one who lied to save his skin and seemed beyond redemption. He had Whitman write a brief letter to his parents that was actually a coded message revealing the location of the Union forces. Alexander Lewis’ Wormley was feverish, cowardly and skittish. In contrast, his tenor blazed fearlessly though the treacherously high vocal part that Aucoin wrote for this conflicted man. It is his bed that Whitman crawled into fully clothed; Wormley later died cradled in the poet’s arms, the only friend he ever had.

Freddie Stowers, one of a man’s thousand slaves, escaped to freedom when he was thirteen. He claims not to have much of a story to tell: he was born, he fought and he fell. Heading north, alone, starving and bereft of hope, he had an apocalyptic vision of mankind’s future on earth that gave him the will to carry on. Whitman is the only person to whom he has ever told his story. I could not but help think of baritone Todd Duncan when I heard Davóne Tines sing. His voice has a similar timbre and he sings with the same easy eloquence. It is a beautiful instrument.

A woman arrives bearing the news that the war has ended. She is shocked that the ruin of a building is a hospital, and by the physical condition of the men. Jennifer Zetlan’s sparkling soprano captured the joy and hopes for the country’s future, but also the horror of the price of victory. Some of Aucoin’s most beautiful music was for those wounded warriors. At times they entered with sounds that dropped from heaven like shooting stars or flashed like a lightening bug on a warm summer evening. In their songs, the men expressed their hopes, prayers and desperation. All were fine singers and actors.

Aucoin conducted A Far Cry, a Boston-based orchestra that played in the first performances of the opera. They were excellent, but I have two criticisms, and one was balance: the orchestra was just too loud much of the time. The other was the dancing. There is no criticism of the performers, but the choreography did little more than evoke the spirit of Martha Graham in Copland’s Appalachian Spring. In the final scene, the stage was crowded and congested as the dancers wove through the cast, who were suddenly in street clothes and miraculously healed of their wounds.

What was the music like? After the performance I was in an elevator with several of the ushers. One of them started singing a tune from the opera, adding when we started to listen that he heard all four performances and didn’t have much of a voice. Try to think of a contemporary opera with a melody that is an ear worm. When Crossing debuted in 2015, The New York Times suggested that Aucoin ‘may be the most promising operatic talent in a generation’. If he has ushers singing his music, he just may be the chosen one.

Rick Perdian