United Kingdom Mahler and Herman Severin Løvenskiold, English National Ballet’s Song of the Earth/La Sylphide: Dancers of English National Ballet, English National Ballet Philharmonic / Gavin Sutherland (conductor), London Coliseum, London, 9.1.2018. (JPr)

United Kingdom Mahler and Herman Severin Løvenskiold, English National Ballet’s Song of the Earth/La Sylphide: Dancers of English National Ballet, English National Ballet Philharmonic / Gavin Sutherland (conductor), London Coliseum, London, 9.1.2018. (JPr)

Song of the Earth

Choreography – Kenneth MacMillan

Staging – Grant Coyle

Designs – Nicholas Georgiadis

Lighting – John B. Read

Dancers included: Tamara Rojo (The Woman), Joseph Caley (The Man) & Fernando Carratalá Coloma (The Messenger of Death)

Singers – Rhonda Browne (contralto) & Samuel Sakker (tenor)

La Sylphide

Original Choreography – August Bournonville

Producers and Stagers – Eva Kloborg, Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter & Frank Andersen

Designs – Mikael Melbye

Lighting – Jørn Melin

Cast included:

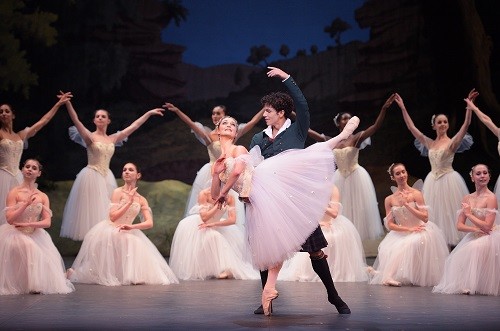

Jurgita Dronina – The Sylph

Isaac Hernández – James

Anjuli Hudson – Effy

Daniel Kraus – Gurn

Madge – Jane Haworth

It was good to see English National Ballet perform Kenneth MacMillan’s Song of the Earth once again. When I first saw this as part of the ‘National Celebration’ of his work – last autumn at Covent Garden – it was ‘tainted’ by being in an unfortunate double bill with The Judas Tree, his deeply misogynist final work that – with #MeToo now in mind – will, I suspect, never be revived again by the Royal Ballet.

MacMillan’s 1965 Song of the Earth, was first choreographed to Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde for Stuttgart Ballet. This was composed by Mahler using verses from Hans Bethge’s Die chinesische Flöte (The Chinese Flute), these were not original Chinese texts but material ‘borrowed’ from other sources. Unusually for Mahler when he used other poetry, here the music is dominant, and he often makes the words fit his music, rather than vice versa. He makes it deeply human, yet there is an unending self-revelatory search for life within the process of dying – and this was a reflection of Mahler the man as much as the composer in 1908, when Das Lied was composed. This was in contrast to all of Mahler’s previous symphonies when he had tended to embrace all aspects of life.

The orchestration is somewhat restrained despite the large orchestra involved – kudos to the excellent English Ballet Philharmonic under Gavin Sutherland – and mirrors the limited pallet of Chinese prints; whilst the use of flute, mandolin, glockenspiel and gongs imbues the music with a certain Orientalism. I am not the first to comment on the rollicking confidence of the beginning that soon becomes more wistfully morose and sober. As the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau put it: ‘A drunk mind speaks a sober heart’! It veers from delicate to snarling and snorting, then there is some wry humour before the heart-wrenching finale. Sung in English or with surtitles of an English translation might have been helpful to see the connection between the texts and MacMillan’s choreography, but the mood of these songs – all the joy, angst, and intimations of the inevitable – is what MacMillan’s ballet gives us.

Each song is distinct, hinting at its subject, with The Messenger of Death, a frequently dominant presence. Apart from the overarching ‘theme’ Song of the Earth has no story and there is constant movement with the tension and atmosphere this creates palpably reaching a crescendo with the contralto’s concluding repetition of ‘Ewig’: MacMillan ‘translates’ this as ‘in midst of the death we are in life.’ His choreography has a unique language though there are homages to Nijinsky and Balanchine, amongst others. Employing only subtle changes of lighting MacMillan uses every part of a bare stage and regardless of how many dancers share that stage at a given time, Song of the Earth never looks busy.

A non-narrative ballet demands acting which is often minimal and therefore somewhat restrained, but acting there must be. I have said it before – and repeat it with great pleasure – how Tamara Rojo remains at the height of her considerable powers. Always a forceful presence, Rojo led her own company from the front showing what someone of her impeccable technique always has, that innate ability to make time seemingly stand still when they dance, as compared to some of her colleagues. Joseph Caley was rather more stoic by comparison and appropriately so. The strong support he provided came more from his flawless execution of MacMillan’s choreography. And as The Messenger of Death, Fernando Carratalá Coloma was elevated from the ranks of ENB’s Artists to replace someone more senior: Rojo has clearly discovered yet another young dancer of exciting potential. When onstage he was confident, commanding, always lurking and menacing, until he claimed his victims. Everyone involved carried out MacMillan’s acrobatics tidily and effortlessly and if I was to single out dancers to celebrate this significant company achievement it would be Senri Kou in the Third Song (Of Youth) and Tiffany Hedman in the Fourth (Of Beauty) who complemented the power of the leading trio so splendidly. Rhonda Browne (contralto) and Samuel Sakker (tenor) valiantly dramatized Mahler’s songs which have sorely tested singers vastly more experienced than they are.

August Bournonville, the nineteenth-century Royal Danish Ballet choreographer and ballet master created more than fifty works for the company. In his own words he described how dance ‘can with the aid of music rise to the heights of poetry. On the other hand, through an excess of gymnastics it can also degenerate into buffoonery. So-called “difficult” feats can be executed by countless adepts, but the appearance of ease is achieved only by the chosen few. The height of artistic skill is to know how to conceal the mechanical effort and strain beneath harmonious calm.’ How true and this perfectly sums up the current strengths of English National Ballet under Tamara Rojo’s inspiring leadership.

Bournonville believed that beauty is forever modern, and the Royal Danish Ballet and other companies still perform his ballets today, nearly 140 years after his death, proving that his belief in this sense of beauty is still very much alive. The Bournonville style is distinctive because of its precision, neatness, lightness, easy elegance and joie de vivre. Repeatedly, we see bouncy jumps, many small quick steps and speedy footwork with beats done while the upper body is held still with arms often in bras bas (or preparatory) position. The latter involves both arms being down and rounded with both hands just in front of the hips, fingers almost touching. This occasionally gives the impression of Irish dancing – whilst when arms are raised in Fifth position it all seems more like Scottish country dancing. However, it was absolutely ideal for his 1832 La Sylphide with its Scottish setting and an Outlander meets Giselle plot.

On the morning of his wedding day, a Scottish farmer named James falls in love with a Sylph (a spirit). She quickly disappears and soon an old witch, Madge, turns up to predict he will betray his fiancée Effy and it will be Gurn that marries her. Although obviously enchanted by the Sylph, James disagrees, and dismisses the witch. With the wedding underway, James starts to put the ring on Effy’s finger when the Sylph suddenly appears and grabs it from him. James abandons his own wedding and chases after her into the forest. There he again sees Madge who offers him a magical pink veil. She tells the enamoured James how it will bind the Sylph’s wings and make her his own. He proceeds to wrap the veil around the Sylph’s shoulders, but when he does, her wings fall off and she dies. Gurn and Effy live happily ever after, James not so!

The idiomatic accompaniment from Gavin Sutherland and his orchestra ideally complemented this amusing, captivating hokum with its ending that packs an emotional punch. Frank Andersen, Eva Kloborg and Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter have lovingly recreated Bournonville’s vision in Mikael Melbye’s exquisitely old-fashioned designs. All the mime and other emoting was so clear that none of the celebrities packing this first night audience – and some with probably no idea of what they were coming to see – could have missed anything about the unfolding tale of James’s love for a sylph and her ultimate tragic ending. The very smiley Jurgita Dronina eloquently embodied the romantic spirit of the Sylph, ENB’s superb character artist Jane Haworth was Madge and through her scenery-chewing performance the story made perfect sense. The bounding and fleet-footed Isaac Hernández gave perhaps a 2018 interpretation of the Bournonville style but excelled as the lovelorn, and ultimately grieving, James.

More wonderful supporting performances from Anjuli Hudson’s pert Effy and Daniel Kraus’s ardent Gurn. Precious Adams proved again she is one to watch out for as First Sylph amongst all the other impeccably-drilled Sylphs. Finally, the pupils from the West London School of Dance and Young Dancers Academy deserve a special mention for their spirited Act I contribution.

Jim Pritchard

La Sylphide is part of a double bill with Song of the Earth or Le Jeune Homme et la Mort until 20 January and for more information click here.