Italy Handel, Aci, Galatea e Polifemo, HWV 72 (1708, ed. Longo/Pe/Guglielmi): Soloists, Ensemble barocco La Lira di Orfeo / Luca Guglielmi (harpsichord / conductor). Livestream from Teatro Municipale, Piacenza, via OperaStreaming (click here) and also streamed via Facebook, 15.11.2020. (CC)

Italy Handel, Aci, Galatea e Polifemo, HWV 72 (1708, ed. Longo/Pe/Guglielmi): Soloists, Ensemble barocco La Lira di Orfeo / Luca Guglielmi (harpsichord / conductor). Livestream from Teatro Municipale, Piacenza, via OperaStreaming (click here) and also streamed via Facebook, 15.11.2020. (CC)

Production:

Director, Set, Costumes – Gianmaria Aliverta

Video Projections – Tokio Studio

Lighting designer – Elisabetta Campanelli

Video director – Tommaso Abatescianni

Cast:

Aci – Raffaele Pe

Galatea – Giuseppina Bridelli

Polifemo – Andrea Mastroni

Handel’s evening-length dramatic cantata Aci, Galatea e Polifemo is a serenata first performed in Naples in 1708 with a libretto by Niccola Giuvo after Book 13 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. This is one of two Handel settings: a masque followed on a decade later in Acis and Galatea, HWV 49 (to a libretto this time by John Gay, but even here there are different versions: click here for a review of the performance at Milton Court by the Academy of Ancient Music and Richard Egarr and here for The Sixteen under Harry Christophers at Wigmore Hall). While Wikipedia would have it that Aci was composed for the wedding of the Duke of Alvito and Beatrice Sanseverino (Naples, 1708), there is some research that points to a commission by the Duchess d’Aliffe, Aurora Sanseverino (a singer, patron of the arts and aunt to Beatrice); we know Aurora had Aci performed at the wedding of her son in 1711.

This was the first performance in modern times of the version ‘for Senesino’ (MS Egerton 2953) with reconstruction and critical edition prepared by Fabrizio Longo, Raffaele Pe and Luca Guglielmi. Also known as a Serenata a tre, as the Giuvo text restricts itself just to the three personages, Aci spreads over some 90 minutes; Handel has all the space he needs to explore emotions in depth. The role of the jealous giant Polifemo is particularly significant in comparison to the later piece.

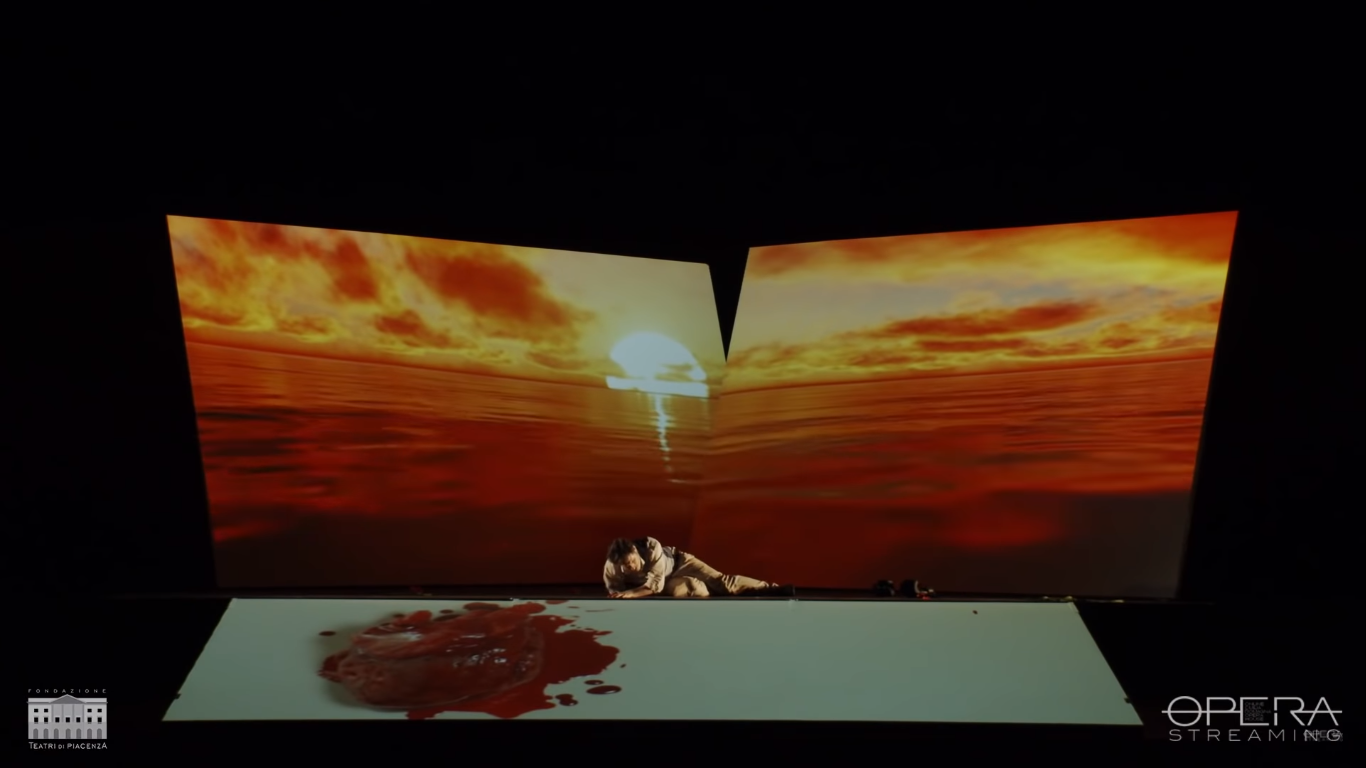

This was a slick production by Gianmaria Aliverta, who also oversaw set and costumes. The production listing above gives a clue as to the importance of video to this production (the projections themselves courtesy of ‘Tokio Studio’). Atmospheric and always pertinent lighting was courtesy of Elisabetta Campanelli. Always resonant with the action and, indeed, with the imagery in the text, the staging was often beautiful in its own right. Nature – be it sea or setting sun – is a central theme (the image of a dawn sun which reflects the text of Aci and Galatea’s duet ‘Sorge il di … spunta l’aurora’ was incredibly striking). ‘The sky seems to glow,’ they sing, and indeed it did. When Polifemo sings ‘Palpito il cor,’ a fire morphed into an ECG heartbeat trace. All this without gimmickry is quite an achievement, but throughout it was clear that it was Handel’s genius that was being honoured. While sometimes obvious, it remained consistently convincing: when stormy emotions are afoot, clouds in the wind are projected as a ‘terrifying bellow’ is remarked upon by Aci; similarly, a close-up of an eye with tears as Galatea sings of dew and tears is a particularly touching gesture. Later, she is shown drowning, ever so slowly, poignantly, and beautifully; the sun sets, as Aci expires.

Excellent English subtitles enabled comprehension for non-Italian speakers. From the off it was clear that the small orchestra was impeccably well-drilled. Strings were 3:3:1:1:1 of particular note was the inclusion of archlute, Baroque guitar (both Giangiacomo Pinardi) and the Arpa doppia (also known as the Baroque triple harp, Chiara Granata). The keyboard component was mainly a two-manual harpsichord, but an organ was also used at certain points. It was, in fact, one of the most imaginative continuo contributions I have come across, period. Some fizzing bassoon contributions from Anna Maria Barbaglia are certainly worthy of note. The harpsichord was fairly forwardly placed, which is more of a positive than a negative – it allowed it to be (pardon the pun) ‘vocal’ in its contribution, underlining Aci’s songs of misery.

It is difficult to pinpoint a ‘star’ of the three singers, and possibly unfair to do so. But Andrea Mastroni’s firm, confident and rich bass for Polifemo was particularly magnificent throughout. Polifemo has his lyrical moments in addition to his barnstormings, Mastroni finding a superb mezza voce at – in translated text – ‘not forever, no, cruel one, will you speak to me like this’. Meanwhile, the opening duet between Aci and Galatea set out their excellence; an excellence that was not to flag. Raffaele Pe’s countertenor voice is incredibly pure; I for one would love to hear him live. It blended superbly with mezzo Giuseppina Bridelli’s Galatea. Vocal decorations from all singers were tastefully done, but perhaps Pe’s agility is worth of special note; balancing this was the odd tuning mishap in the later stages of the performance.

When Bridelli sings ‘the stars that smiled upon your suffering strain to weep with greater sorrow’, we hear the full magnificence of Handel’s use of dissonance, fully embraced by the performers. Magnificent. Bridelli relishes each syllable yet projects a legato line – on video, one can clearly see how her mouth enunciates.

A fabulous performance that moved from fierce energy to the most tender emotions, always stylistically but always, importantly, believably. If anything, it was even more impressive than the recent Purcell Dido and Aeneas (click here). Some operas in this series have inevitably been cancelled: an Otello from Bologna on 18 November and a Madama Butterfly in Ferrara on 29 December. Next up, Werther from Modena on 27 November.

Colin Clarke