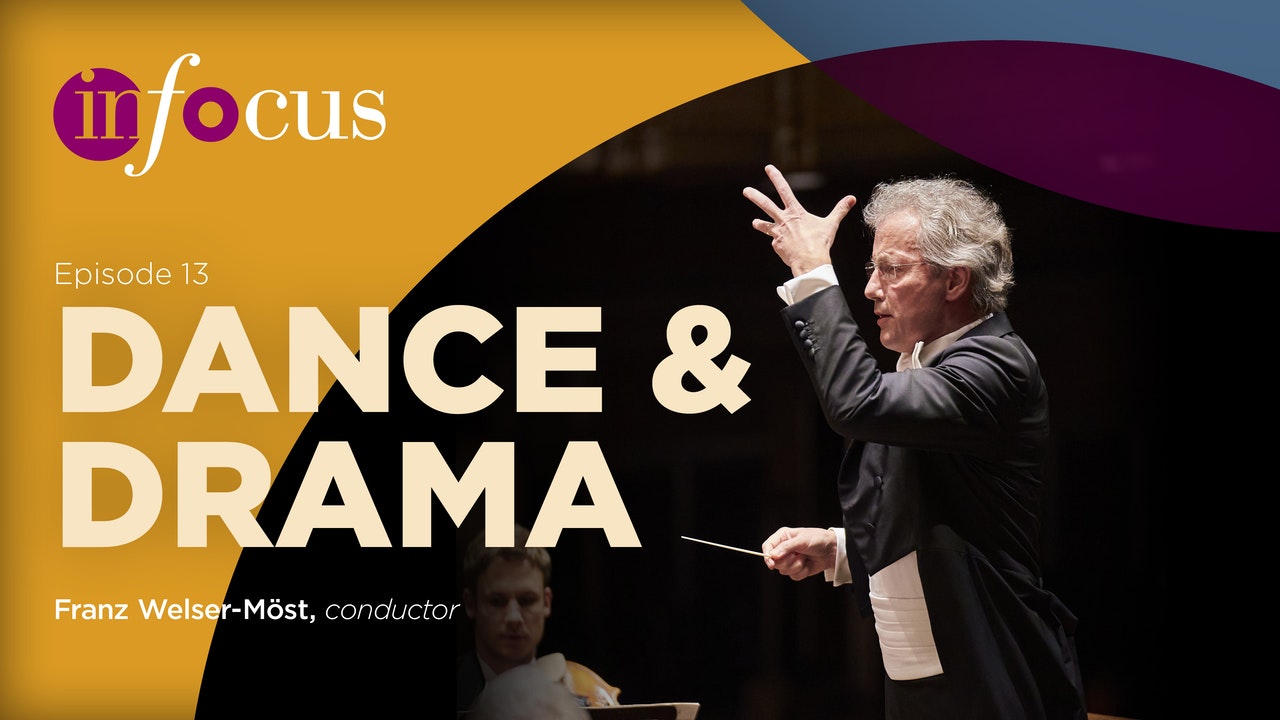

United States In Focus / Episode Thirteen: Dance & Drama: Strings of The Cleveland Orchestra / Franz Welser-Möst (conductor). Performed in Severance Hall, Cleveland, recorded 30.3 and 2.4.2021 and streamed from 17.6.2021. (MSJ)

United States In Focus / Episode Thirteen: Dance & Drama: Strings of The Cleveland Orchestra / Franz Welser-Möst (conductor). Performed in Severance Hall, Cleveland, recorded 30.3 and 2.4.2021 and streamed from 17.6.2021. (MSJ)

Grieg – From Holberg’s Time

Korngold – Symphonic Serenade in B flat major Op.39

The Covid pandemic has been a beast to performing arts organizations worldwide, but it has allowed some enterprising ensembles the opportunity to show what they can do with a challenge. The Cleveland Orchestra responded to the crisis with their In Focus series of concert streams – here in its final episode of the first season – to keep presenting music. The repertory has been intriguing and moving, combining the expressive needs of an extraordinary time with the desire for some familiar signposts along the way. The series has also made use of interviews with musicians to help listeners witness the connection players and conductors have to the works they perform. In short, it has been a brilliant way for the orchestra to pivot, serving both local and world communities in a time when the solace of music has been sorely needed. Happily, even after the return of live concerts, the series will return in the fall. It must be a godsend to music lovers no longer able or willing to venture out.

The final concert of the series combines a familiar favorite with a rarely-heard masterpiece. Edvard Grieg’s suite From Holberg’s Time evokes the bygone era of Norwegian writer Ludwig Holberg with warmly expressive and joyous music, and this performance under music director Franz Welser-Möst fully savored the work’s charms.

Particularly pleasing was the vigor of the opening movement, but especially the feathery delicacy of the quiet moments. Welser-Möst’s use of the full range of the ensemble’s dynamics gave the music a real sense of playfulness. The following sarabande was given sonorous space without ever sagging into indulgence, while the gavotte emphasized Grieg’s mischievous accents, never losing the pulse of the dance the composer was evoking.

The slow second movement, an air marked ‘andante religioso’, sometimes grows cloying in performances that attempt to overburden the music with sentiment. Welser-Möst instead kept his focus on the flow of the music so that its upwellings came and went coherently. This approach allowed room for the strings to dig in sonorously without ever losing elegant poise. Likewise, the conductor didn’t turn the minor-key middle of the final rigaudon into another slow movement, keeping its vital momentum alive. The outer sections, led by the fiddling figurations of acting concertmaster Peter Otto and principal viola Wesley Collins, were pure joy.

Franz Welser-Möst has been a persuasive advocate for Erich Korngold’s music for decades, dating back at least to his award-winning recording of the Symphony in F sharp with The Philadelphia Orchestra. It’s a worthy project, as Korngold was truly a masterful composer. It was his misfortune to fall out of the increasingly serial mainstream of the twentieth century, and to be further isolated from the music elite by making a highly successful living as a composer of film music, the gainful employment Korngold found in the US after fleeing the Nazis.

While there are plenty of predictably lovely moments in Korngold’s Symphonic Serenade, he also used it as a canvas for his ability to paint moods and scenes. Most of the first movement is lively, but there is a quiet passage that can make the hair stand up on the back of one’s neck, it is so uncanny. Even in the lively parts, there is a volatility that will keep the listener on his or her toes. When this music was written after the Second World War, it was seen as hopelessly old-fashioned. But now, when fashion of the day is removed from the equation, one can only wonder how so many listeners missed the signs of a genius at work.

The second movement scherzo starts with pizzicato strings like the scherzo of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony, only here the patterns are even more jumbled and tipsy. Passing bowed moments tingle with otherworldly unease. Like the Grieg, this work has a slow movement with religious connotations, but here the conductor and players rightly seek more anguished, Mahlerian sonorities. The finale closes this amazing work with even more rousing invention. One can only hope it remains a regular visitor in Cleveland or, perhaps, gets issued as one of their TCO releases.

Mark Sebastian Jordan

Subscriptions to The Cleveland Orchestra’s Adella streaming app are available at Adella.Live or on their website: click here.