Poetry Truth and Understanding. That trinity comes out from my church-attendance friends as God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Ghost. Pontius Pilate was almost as witty as Jesus himself. My vote for the fifth Prefect of Judea goes with the Orthodox Church’s, who revere him as a hero: unlike the spoilsport Western Church, who portray him as a villain. What is truth? is the question that the Godhead Himself must constantly ask as well as urge his followers to ask. Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s and unto God the things which are God’s says Jesus, in the response to the Pharisee’s trick question as to whether it is lawful to pay your taxes. Good Christians do well to follow Our Lord’s advice. So, no apologies to the super-taxed wealthy. And absolutely no excuse for your responsibilities toward God. Those responsibilities are both complex and a delight. Further thought is needed.

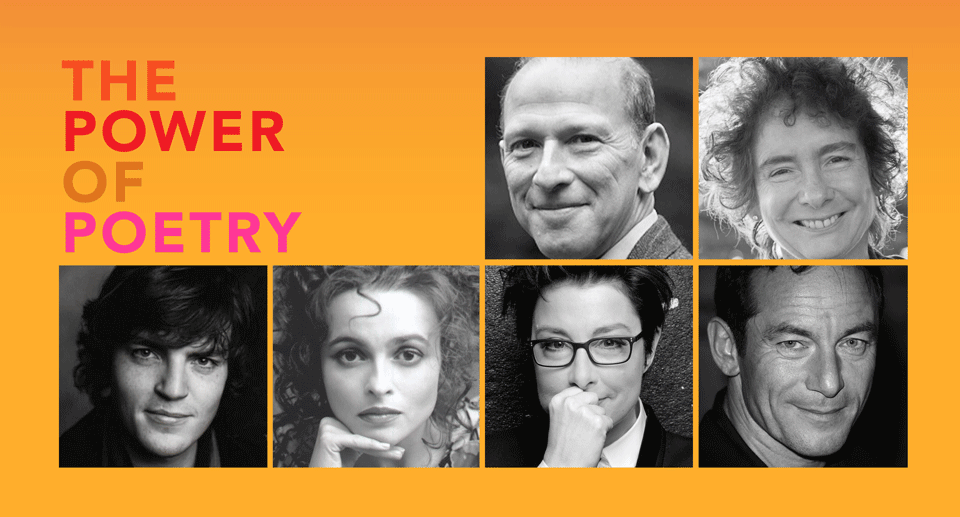

Intelligence2 has just aired an outstandingly helpful programme on your TV, for all who wish to explore these responsibilities. It is chaired by a headmistress-ish-looking woman, Sarah Montague (the nicest sort of headmistress) who is refereeing ideas about poetry between William Sieghart and Jeanette Winterson, who both have invitations for us to consider The Power of Poetry. Actors and poets, Helena Bonham Carter, Jason Isaacs, Tom Burke, and Sue Perkins make some stimulating contributions in poetry readings, and impressions.

Jeanette Winterson has been pondering these questions with a rare and refreshing honesty, which you will know if you have read Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit which was her first, hugely successful novel – a thinly disguised autobiography to be followed by a memoir, and other thought-provoking works of fiction.

Jeanette was plucked out of a cradle in a Manchester orphanage to be brought up by Mrs Connie Winterson who was an evangelical Christian who lived in darkest Accrington in North East Lancashire. The only book in the house was the Bible. That was fortunate, in that Jeanette was obliged to become extremely familiar with it at a time when others of her generation were not. The terraced cottages of Water Street were thrown up as miners’ houses (two up and two down, loo in the backyard) and stretched up a hill from centre of town to the coppice, an open space well short of a mountain, which gave you a good view of the dreary metropolis below. Jeanette showed BBC’s Alan Yentob the doorstep on which she frequently slept on the many nights she returned home after Mrs Winterson’s curfew. Accrington Stanley’s football ground is up an adjoining street.

I am Accringtonian too, though not from Water Street or proselytizing, evangelical parents. I did just what Jeanette did: got the hell out of the dump as fast as I could, some twenty years before her. Still, not like Jeanette, who tutored herself for O and A levels on the steps of Accrington’s public library. (Me too: I lived conveniently round the corner; George Oldham had left all his vocal scores of G&S to the library. I would pick up one score in the morning, play it and sing it, and take it back for another in the afternoon. Repeatedly. Ad infinitum. No better indoctrination!) With a few prompts from the College of Further Education, Jeanette won an open scholarship to St Catherine’s College, Oxford, where there was no curfew and her favourite activity – reading – was vigorously encouraged. Her tutor was the Australian, Michael Tosh, who believed English studies should be fun. Michael could indeed not have found a better student than Jeanette for that approach.

All poetry is oral as well as aural: sound as well as speech. All poets know that writing comes after (sometimes centuries after) the oral-aural origins. When words swing and wing themselves into existence it’s called music. Just listen to Helena Bonham Carter or Jason Isaacs reading a poem and you will hear them winging and swinging into existence. Now try speaking aloud a poem or rhyme you know. Listen. You should hear that you are a poet and musician even if you never thought of that.

In 1990 something truly astonishing happened. The American poet Robert Fagles (1933-2008) wrote a translation of Homer’s Iliad to be followed in 1996 with Homer’s Odyssey. Both translations sport an explanation of how Fagles accomplished this feat from the poet’s friend, student, and professor of classics at Princeton, Bernard Knox (1914-2010) – a Yorkshire man who took American citizenship along with his Chair at Princeton. The explanations are longer than the poems, but they are also so well written that no reader of above average intelligence would have any difficulty understanding. Previous translations now seemed awkward, jolted and unmusical. Fagles sings and wings. To be sure, there are moments when Fagles jolts. Knox explains that that is because the original poet himself does. And why he does it. This is somewhat like a composer today writing a piece in 4/4 time when he discovers he needs a bar in 5/4 time, thereafter immediately returning to the original time. Hear and enjoy the jolt.

Poet and compiler of many anthologies, William Sieghart, makes a wonderful contribution to this debate. He is the Founder of the National Poetry Day and the Forward Prizes for Poetry. He also does something which I have been doing myself: inviting people to chat with him on some deep problem they are having for which a poet might offer some words to ponder. Aptly, he calls it ‘The Poetry Pharmacy’. The Poetry Pharmacy (TPP) is a published collection of poems which have been found valuable to the ‘patients’. Its subtitle says it all: Tried and true prescriptions for the heart, mind and soul.

I live in a comfortable care home for old crocks, in sheltered housing, which is to say that residents are independent and able to cater for their own needs, including shopping and food. I can still have lunch provided if I give a day’s notice. There is also a full care section which gives two meals a day and has paramedics 24 hours a day and social activities. During lockdown, those social activities are not allowed, and neither are social trips to theatres, exhibitions, and such like. Whitgift House and its satellites was the invention of Archbishop Whitgift and his mother, in the reign of Elizabeth I. It has three distinguished independent schools, three care homes and two sheltered housing complexes. The Whitgift Foundation is Croydon’s biggest landowner and ploughs its huge rents back into its charities, which includes care as well as education.

The original almshouses are a Grade I listed building. Everyone has forgotten that right up to the Labour government of Clement Atlee, it was the Church that was responsible for education and health. And then as now, the quality of both services varied from zero to magnificent, depending largely in which part of the country you lived.

Before lockdown Whitgift House also had day care: other old crocks – who were picked up in the morning – came for the activities and lunch and were taken back home at 5pm. It was for this group that I ran my poetry class. And how good they were, even if I say so myself! Those suffering from the worst dementia were producing the best poems. To wind them up, I would often begin with a singsong. Of course, this also unwound them too. I would chatter to them in ‘language’ I made up. Then got them to make up languages. They were terrific at this. We clapped and tapped rhythms. Fortunately we live in an age of rap. Edith Sitwell would have applauded this. So did my General’s widow. They loved limericks: There was an old woman of Ryde / Who ate some green apples and died./ The apples fermented inside the lamented / Making cider inside her inside.

The shortest poems make the greatest effects. Less is emphatically more here. Just as it is in acting. Or playing a Mozart sonata. Here is a poem called Celia Celia by Adrian Mitchell in TPP:

When I am sad and weary

When I think all hope has gone

When I walk along High Holborn

I think of you with nothing on

Or Come to the Edge by Christopher Logue in TPP:

Come to the edge,

We might fall,

Come to the edge,

It’s too high!

COME TO THE EDGE!

And they came,

And he pushed,

And they flew.

Or one of my own shorts:

Jest a moment, the young woman said.

What would you do? Stand on your head?

Chances like this are best,

Never held subject to jest.

Here are some familiar words of John Donne which in the context of the Sieghart surgery invite other challenges:

No man is an island,

Entire of itself;

Every man is a piece of the continent,

A part of the main;

If a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less,

As well as if a promontory were,

As well as if a manor of thy friend’s

Or of thine own were;

Any man’s death diminishes me,

Because I am involved in mankind;

And therefore never send to know

For whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.

Donne’s words are so carefully chosen (skip the grammatical ‘error’ in the penultimate line) and read each one of the fourteen lines as a separate poem. Fourteen poems. No prizes for spotting the Brexit folly. Fourteen prayers. Make them yours. You then experience the genuine power of poetry. And its musicality.

And herewith the briefest advice from the incomparable Wendy Cope:

Two Cures for Love by Wendy Cope

1. Don’t see him. Don’t phone or write a letter.

2. The easy way: get to know him better.

Jack Buckley

The Poetry Pharmacy by William Sieghart is published by Particular Books – an imprint of Penguin Books.

The Power of Poetry with William Sieghart, Jeanette Winterson, Helena Bonham Carter, Jason Isaacs, Sue Perkins, and Tom Burke, with presenter Sarah Montague (130 minutes) is available on the Intelligence Squared channel (click here).