Hungary Gounod, Busoni Faust 225 Festival, Hungarian State Opera, Orchestra and Chorus, State Opera House, Budapest (Festival ran 17 May to 1 June) (RD)

Hungary Gounod, Busoni Faust 225 Festival, Hungarian State Opera, Orchestra and Chorus, State Opera House, Budapest (Festival ran 17 May to 1 June) (RD)

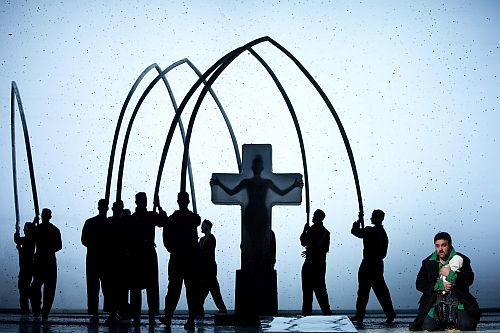

Gounod: Faust d Michał Znaniecki, c Maurizio Benini

Dario Schmunk (Faust), Gábor Bretz (Mephistophélès), Andrea Rost (Marguerite) 21 May

Buson: Doktor Faust d Máté Szabó, c Gergely Vajda

Csaba Szegedi (Faust), Boldiszár László (Mephistopheles) 23 May

The Hungarian State Opera is responsible for the upkeep and programming of two large opera houses in Budapest. The State Opera, or Magyar Allámi Operaház, the magnificent late 19th century building designed by Miklós Ybl, one of the finest in Europe, is the smaller, housing 1300, but feels far more spacious and handles most of the major premieres. The Erkel Theatre, named after Hungary’s great opera composer, was refurbished last season and at 2400 has the largest capacity in the country. It also has the honour of presiding over the square where the most important revolutionary exchanges took place in the anti-Communist uprising of 1956.

The company is currently embarked on ‘The Month of Dance’, a major month-long celebration of ballet at the Erkel, including an evocative exhibition exploring its wide repertoire. Next season’s brochure – 550 pages of it – for both houses has just been issued, and one of the highlights will be a celebration in May 2016 of Shakespeare, on the 400th anniversary of the playwright’s death: a two week bonanza which will include, in one form or another, Reimann’s Lear, Bernstein’s West Side Story and Thomas Adès’ The Tempest, as well as two versions of The Taming of the Shrew: Wolf-Ferrari’s Sly and Goldmark’s ballet. Purcell, plus Bellini and Gounod (making three versions of Romeo and Juliet), Verdi, Nicolai, Szokolay (Hamlet): more than a dozen different stagings, several of them new, plus a couple seen in concert.

The May Festival has now become a regular undertaking for the State Opera, under its General Director, Szilveszter Ókovács, who has taken the company forward in many respects: securing additional state funding, revising old-style contracts, enhancing publicity, and having a hand in every aspect of repertoire planning. Perhaps most important of all, raising morale – a key feature of company leadership.

Last season saw the most substantial tribute to Richard Strauss festival staged anywhere – six operas: Die Frau ohne Schatten, Arabella, Salome, Elektra, Ariadne, Rosenkavalier. This year Budapest opted to celebrate the (on one view) 225th anniversary of the first publication of Goethe’s Faust. The opera programme was typically wide-reaching, a feast of mischief-making and malpractice. Included were Nick Shadow (Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress) directed by Ferenc Anger, and Kaspar and Samiel – the evil forces in Weber’s Der Freischütz, for which the cutting edge theatre director Sándor Zsótér was teamed up with designers Mária Ambrus and Mari Benedek.

The last two are regular collaborators with Balázs Kovalik, still Hungary’s most celebrated avant-garde opera director, though currently based in Munich. It was Benedek (costumes) and Csaba Antal (set) who teamed up with Kovalik on yet another of Budapest’s highlights, dating back three or more seasons: Boito’s Mefistofele – impudent, sly, presumptious – was revived as part of the present

Festival. No Berlioz (or Spohr, whose Faust was one of the more successful operas of the Beethoven period); but the centrepiece of this festival saw new HSO productions of Gounod’s Faust and Busoni’s Doktor Faust.

The results were marvellous. Ókovács has taken the decision to show surtitles of all operas in English as well as Hungarian, the benefits of which can already be seen: certainly it offers American and British, and many literate western European visitors the chance to follow the sung text, be it in Hungarian, (as here) French, German, Russian or Czech. As it happens, the surtitles failed in the first act of Faust, which gave one the chance to admire the lucid French diction of solos and chorus alike: it was a minor hitch.

As it happens, the opening impact – a superb one – was achieved without any words. As conductor, the HSO, who are increasingly drawing on top western performers – singers, designers, and here conductor – to supplement home-grown resources, had employed the renowned Maurizio Benini, veteran of Paris, The Royal Opera, Vienna, Bologna and La Scala, Milan, who will doubtless work with them again – and who is an expert on this particular opera, having conducted it seven or eight times.

The benefits showed from the outset: the quality of the opening string playing set the tone for the whole evening: an overture of thrilling intensity, with dense low strings especially compelling. Benini produced many notable effects from the HSO players, superlative at their best: vigorous cross-rhythms for the celebrations (here, virtual discos); delicacy and charm for the rustic girls’ dances; a miraculous passage early on pairing harp and horn; and an Act 3 overture that recalled Berlioz, but most notable for eloquent solo clarinet; twinges of perfect violin solo. All – cellos and basses, violin, clarinet, return in the last Act for Marguerite’s bold affirmation.

This was an opera with a glorious set of leads – the triangle, Faust, Marguerite, Mephistopheles – around which the drama is mainly shaped. Andrea Rost, one of Budapest’s most seasoned performers, took on Marguerite. Quite small and petite, she had no difficulty in looking increasingly like a schoolgirl, which is actually how Gretchen should look. The voice is wonderful – rich, full-bodied, varied. Her sad Act 3 air (beginning ‘Il était un roi de Thule’ with woodwind following in turn), and excited cabaletta (‘Ah! Je ris’) as she is dazzled by tantalising jewels, were as dazzling as the passage where Marguerite sings over the chorus in Act IV: intense, energetic.

The Argentinian tenor Dario Schmunck was certainly a find for the role of Faust. Well known at the Vienna Volksoper, as well as in Hamburg, Venice’s La Fenice and the Teatro Colon in his native Buenos Aires, Schmunck has a strong, in some ways Wagner-quality voice and the ability dramatically to suggest an older presence as well as a youthful one – which of course is what Faust needs. The sound was superlative from Faust’s first utterance. The character came over well: some of the time, tamely in train to Mephistophélès, at others, boldly assuming the lead. A congenial performer in every respect, and this served the part and the ensemble well.

But the energy, and the fun all rested with Mephistophélès. Gábor Bretz, so awesomely still and threatening as Bartók’s Bluebeard a season ago, produced a delicious comic manipulator, always sparky, fidgety and mischievous, whether cavorting around in a wheelchair (wheelchairs, nominally for Valentin’s wounded military veterans, were ubiquitous in this show; at a later point he cheekily potters off with caddy in a golf buggy); or floating around in a white coat (some paradox here?), or entering as a bishop or cardinal. The voice is magnificent, always, one senses, with something in reserve. The tone at the top and bottom of the register is equally resplendent: no one has any doubt he is one of Hungary’s finest, and indeed with good reason he has been swept up to perform, intermittently, in America.

But the minor roles stood out too. Most obviously the doomed Valentin (Zsolt Haja), strong and cheerful as the military prepares to set out (a slightly weakly directed crowd scene), passionate in ensuring the safety of his younger sister, and then veering to the opposite upon his return – sensing betrayal, hurt to the point of cruelty and indifference, and finally long in expiring, in winding cloth, like those pictures of Nelson’s time. But even in as modest a role as Marthe, Bernadette Wiedmann provided a charming, tuneful vignette; Lajos Geiger was cheerful in the here much truncated role of Valentin’s friend Wagner – a key figure in some other Faust operas; and best of all, Szilvia Vörös brought a profound pathos to Siebel, the submissive trousers role figure, here usually with broom in hand, who is hopelessly in love with Marguerite, and would do anything to protect her. When much of the opera found a comic dimension, Siebel’s yearning added a new aspect: aching loneliness verging on despair.

But the set and costumes and lighting departments united to give the Gounod a field day. This was partly because the oval design with which Bretz’s Mephistophélès is depicted at the rear – a curious two or three dimensional effect – was so inviting: here were Scoglio’s summery green fields, full of country folk into which Faust escapes from his cobwebby study. The effects of Bogumil Palewicz’s’s lighting, especially in the switching from bright colours to subdued evening cloud in pastels, were quite magical. At the same time, Costume Designer Ana Ramos Aguayo kitted Mephistophélès out in fresh-off-the-peg summery attire in glowing colours: it all contributed to the feeling that Mephisto was smugly biding his time: he was in no rush; Faust would fall into his clutches in the end; in the meantime, why not grab a deck chair and impishly enjoy a holiday?

What made Znaniecki’s staging so eminently worthwhile was that everything meshed; true, we have seen wheelchairs in opera before, but they only work when they play a consistent role and convey a meaning. Every aspect of set and costumes seemed to gel, from the plush French blue hues of the soldiers setting out to the chicanery with which Mephistophélès gratifies Faust’s whims while nonchalantly preparing his downfall.

It was this kind of consistency which also worked so well in Doktor Faust – Busoni’s in many ways musically advanced opera score; one that called to mind such modern if not modernist German composers as Hartmann and Hindemith: we were guaranteed, somewhat apologetically, a ‘semi-staging’. But from the tolling bells at the outset – a truly splendid piece of musical counterpointing – in which conductor Gergely Vajda equalled those top-class strings of Benini in the Gounod, and Designer Csörz Khell’s restrained evocation of Faust’s study at the start, the blackboard riddled with calculations, this production by Máté Szabó worked at every point. The set was peopled with ideas; there was atmosphere. You could tell something was afoot.

Boldiszár Lászlo and Csaba Szegedi competed for attention in the main roles – Mephistophélès and Faust – Lászlo perhaps not quite comfortable with his attire, but painting a reflective figure, one distinctly less frenetic than Bretz in the Gounod. The score makes much of Bach-type chorales over a moving bass, but even more of a series of quick-moving scherzos, sustained by rippling low woodwind, one of which suggested a horse ride, others of which were enhanced by particularly well-defined brass, including some distinctive contributions from tuba.

The abbreviated version used (partly owed to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau) leaves us concentrating rather specifically on the wedding celebrations of the Duke and Duchess. Fortunately these roles were both particularly well sung: Ferenc Cserhalmi made an engaging Master of Cerermonies. Tamás Busa produced an enticing tenor (I assume) as the Duke which brought both solemnity and dignity, and more, a striking lyricism. His costume, by Anni Füzér, was particularly attractive, with red prominent, braided with gold. Even more dazzling was the assertive Duchess, Éva Bátori, undoubtedly one of Budapest’s stars, who engages in amusing shenanigans in her obvious and almost instant attraction to Faust. It is for her delectation that, with Mephistophélès’ conniving, Faust conjures up King Solomon and other apparitions, first in court, and then in the tavern at Wittenberg.

Much of what follows – dealing with a straw doll which Mephistophélès makes Faust believe is his child, presumably with the Duchess – is a gradual, systematic decline towards Faust’s inevitable expiry. ‘Vorbei ist da Werk’ – an echo, one might think, of

Haydn’s Creation, or Christ’s words from the cross, or both. Máté Szabó’s closure has the success of suggesting both finality and continuity. We are left in a kind of emotional limbo; but it is as if the whole saga is simply a cycle waiting to happen again.

Roderic Dunnett