United Kingdom Alfred Brendel Lecture – Schubert’s Last Sonatas: Wigmore Hall, London, 7.1.2017. (CC)

United Kingdom Alfred Brendel Lecture – Schubert’s Last Sonatas: Wigmore Hall, London, 7.1.2017. (CC)

Part of the “Wigmore Hall Learning” series, this fascinating lecture of just over an hour’s duration is part of a series of three lectures Brendel will give at this venue: “Beethoven’s Last Sonatas” follows on on June 3, while “On Playing Mozart” concludes the mini-series on July 8.

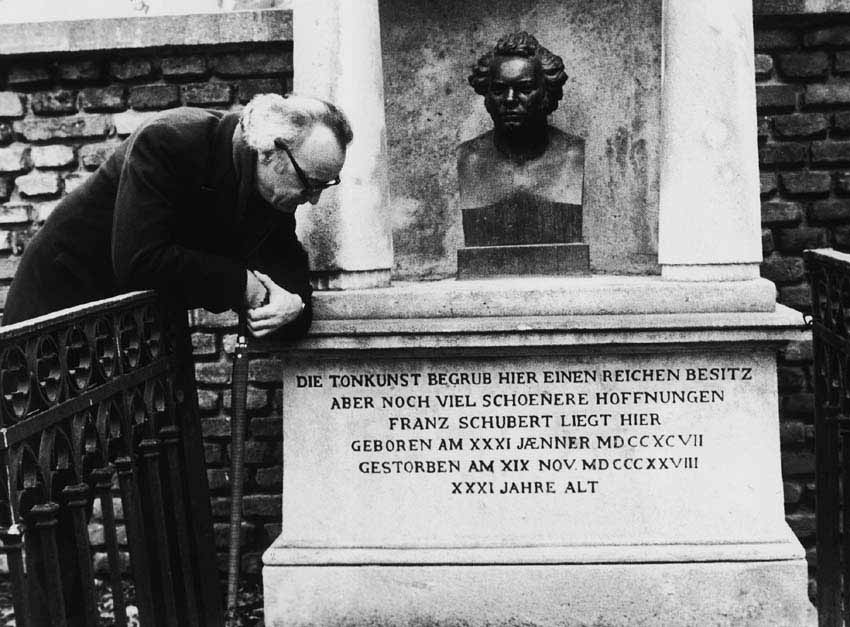

Although now retired from the concert platform, Brendel did play brief examples from the repertory under examination. Complete movements came from recordings (by himself, one assumes, including one which included tumultuous applause that found Brendel gesticulating wildly for it to be cut off). As a lecturer, Brendel is articulate and engaging; the packed audience seemed to lap up his pearls of wisdom. In some circles it has been a cliché to refer to Brendel’s playing as “too academic”. He has always been a great musical thinker – I remember the impact Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts had on me as a teenager – and this lecture just confirmed the depth of his insights. A specific aspect of Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts which found an echo here was the identification of orchestral instrument sonorities in the slow panel of D958.

The lecture was recorded, so one hopes it will see the light of day at some point: a summary such as this can do Brendel scant justice. After a markedly affectionate welcome from the audience, Brendel focused on Schubert’s late trilogy of sonatas, quoting Schoenberg in 1928 on Schubert’s originality and highlighting the way this music had slipped into relative obscurity, with only a handful of adherents (Schnabel and Erdmann, for example). Emphasising that the three Schubert sonatas of 1828 form a trilogy, published eleven years after Schubert’s death, Brendel sought out connections in the music while also honouring the extrovert, sometimes explosive nature of this music. To that end, he gave us the sudden eruptions of these sonatas as well as referring to that bass B-flat trill in D960 as the “disclosure of a new dimension”. As Brendel put it, these works are not only structures, but characters.

The question of repeats, too, was squared up to, Brendel quoting the example of Dvořák repeats as a time where perhaps they are best omitted. The works outside of the trilogy Brendel spoke of were often well-known but always prescient: Erlkönig, the Schubert String Quintet, Beethoven’s C-minor Variations. But it was in his turn of phrase that the most cherishable moments lay: the “melancholy clairvoyance” of the slow movement of D960 being a case in point. Brendel believes, correctly, that these final three sonatas should be performed together in one long but unforgettable evening.

Brendel’s mode of discourse includes flashes of his well-known wit as sparks within a delivery that oozes the wisdom of a lifetime’s immersion in this music. One waits with some impatience for the next instalment.

Colin Clarke