Germany Weber, Der Freischütz: Soloists, Chorus of the Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerisches Staatsorchester / Antonello Manacorda (conductor). Livestreamed from the Munich National Theatre, 13.2.2021. (JPr)

Germany Weber, Der Freischütz: Soloists, Chorus of the Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerisches Staatsorchester / Antonello Manacorda (conductor). Livestreamed from the Munich National Theatre, 13.2.2021. (JPr)

Production:

Director – Dmitri Tcherniakov

Set design – Elena Zaytseva

Lighting – Gleb Filshtinsky

Video – Show Consulting Studio

Artistic consultant -Tatjana Wereschtschagina

Dramaturgy – Lukas Leipfinger

Chorus director – Stellario Fagone

Cast:

Ottokar – Boris Prýgl

Kuno – Bálint Szabó

Agathe – Golda Schultz

Ännchen – Anna Prohaska

Kaspar/Samiel – Kyle Ketelsen

Max – Pavel Černoch

A Hermit – Tareq Nazmi

Kilian – Milan Siljanov

Four Bridesmaids – Eliza Boom, Sarah Gilford, Daria Proszek, Yajie Zhang

Der Freischütz surfaces only from time to time in Britain and it is difficult to know why this is. It was performed by Sadler’s Wells Opera in its heyday and is long overdue a staging by English National Opera (though who knows what the future holds for them post-Covid?). Carl Maria von Weber’s 1821 melodrama is perhaps the prototypical nationalistic opera and its adoption in the twentieth century as an instrument of Nazi ideology has not helped its reputation. Indisputably Der Freischütz is a landmark of the German Romanticism which reached its zenith in the works of Richard Wagner (indeed the opera can be considered a precursor to Der fliegende Holländer). I am approaching my fortieth anniversary with this wonderful work, and I remember – with increasing fondness as years pass – when it was on at Covent Garden in 1982 with Alberto Remedios as Max, Donald McIntyre as Kaspar and Colin Davis was conducting. Since then, in the UK there has only been no more than the odd opera house revival – it was last on at Covent Garden in 1989 – and a few concert performances as far I can recall. Der Freischütz is still regularly performed across the Channel and especially in Germany, as here, of course.

Since Weber’s opera involves magic and the eternal battle between good and evil it is open to ideological misinterpretation. It concerns a marksman who makes a pact with the devil to win a shooting contest and we are not far removed from similar parables such as Goethe’s Faust or even the Ring. It is based on a fifteenth-century legend about Bohemian foresters and their magic bullets (or arrows) which will always find their target, but which also brings the risk that the devil will direct one of them at the shooter himself. In Johann Friedrich Kind’s libretto, all the shots by the young huntsman, Max, seem to miss. A rival hunter, Kaspar – the prototype for similar operatic villains with malignant dispositions – has earlier made that pact with the devil to trade his soul for magic bullets. He hopes to exchange Max for himself since Max’s last shot will kill Agathe, the hunter-hero’s bride-to-be.

If you think it all sounds a bit Grimm, then you are quite right because the plot of Der Freischütz springs from the same kind of folklore with just a little more horror and suspense added. Weber engineers a typically happy ending when a holy hermit arranges that Agathe is kept safe by a bridal crown of white roses, as Max’s bullet kills Kaspar and the devil claims him.

I have always been attracted to this opera and as if the story were not enough, it has all the musical ingredients to keep it popular: an endlessly melodious score whose tunes are very familiar and include the famous overture, Agathe’s aria ‘Leise, leise’ (‘Softly, softly’), and the wonderfully atmospheric Wolf’s Glen scene. Other works that are revived endlessly offer much less. On the downside, there is the dialogue that moves the tale along but punctuates the work to make it a ‘number opera’ that is very typical of its time – but then dialogue has never prevented Carmen from being, quite probably, the world’s most popular opera. Dmitri Tcherniakov uses an overarching Konzept to attempt to bring greater coherence to Der Freischütz than is sometimes possible. Whether he entirely succeeds I am not too sure and, for me, Tcherniakov has eliminated nearly all the ‘German Romanticism’ that first attracted me to the opera four decades ago.

There is a permanent set (from Elena Zaytseva) and we are in a modern penthouse office suite with a curve walnut-coloured panelled wall which will open up to revealed panoramic windows at the back. To explain all that we will see and hear Tcherniakov includes a preface during the overture – and shown on the video screen above the stage – explaining how the independent Agathe is estranged from her father Kuno, described as the ‘Owner of a big company. Authoritarian. Despotic.’ We learn how Agathe’s fiancé Max is ‘very ambitious’ and hoping for promotion in Kuno’s company. The way Kuno mistreats Max shows he is not good enough for him, either for his company or his daughter. Ännchen is described as Agathe’s friend and as ‘successful, independent, pragmatic’. In some ‘texting’ we see a one point above the stage Ännchen complains how Agathe has chosen ‘the life of a housewife – children, kitchen, church’ and it is clear theirs is a very close relationship and Ännchen is obviously jealous of Max.

Everything begins at 1pm on one day during an alcohol-fuelled business reception in a high office block and ends at 12pm the next at the wedding of Max and Agathe. We are told how Max ‘wants to join in Kuno’s innermost circle and be respected’. Even though he seems only too eager to please, he is an unwilling participant in a shooting competition used to prove his worth and as a part of his initiation. Max hasn’t it in him to kill ‘a living being’ and it is Kilian who is shown shooting a random stranger in the plaza below (though this will later be discovered to have been faked simply in order to intimidate Max). Kasper exudes bonhomie, but this just hides his schizophrenia as a result of PTSD and we eventually learn he believes himself to also be Samiel, the devil who we hear from in the Wolf’s Glen scene. It is clear that by then Max has become the knife-wielding Kaspar’s victim as he is dragged in shrouded in plastic sheeting.

© Wilfried Hösl

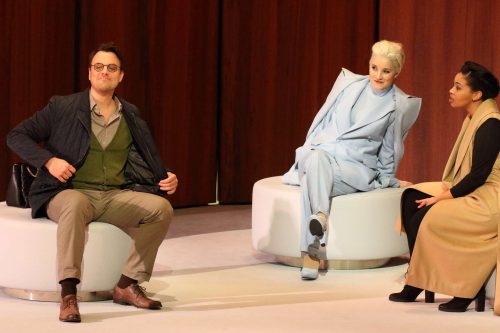

Ännchen has short blond hair and is power-dressed in pale blue and seems to want to do everything to discourage Agathe from marrying Max. Far from being a mistake, it was probably Ännchen, herself, who arranged for the funeral wreath Agathe receives. For the final scene, Ottokar, the prince, is the master of ceremonies at the black-tie wedding. A drunken Max turns his rifle on Agathe and shoots her, but surely this is another fake death? The ‘Hermit’ – who saves the day and has protected Agathe from the magic bullet – is simply one of the masked waiters who have been fussing around and clearing up. Indeed, Agathe has only fainted due to shock and it is Kaspar who has been killed. Max confesses ‘I have been weak, but I am not an evil man’, and the Hermit proposes a year’s probation. With Max spotlit on a darkened stage it ends in the usual prayer of thanks whilst in slow motion all are reconciled. The giveaway is that Max remains laughing hysterically and as the lights come up for the last time [spoiler alert!] it is only Max’s self-delusion we have witnessed, as it is Agathe in her white wedding gown who is dead, with Kasper still very much alive.

From Antonello Manacorda and the Bayerisches Staatsorchester there was verve, myriad bold orchestral colours, and all the necessary bucolic, as well as suitably eerie and demonic sounds. Whilst sufficiently dramatic it was slightly at odds with the stage pictures. The conductor and his excellent orchestra were well-supported by a very committed chorus as corporate types (though ‘originally’ peasants, huntsmen, or spirits).

Pavel Černoch’s brought burnished tone to Max and there was an expressive earnestness to his singing that was perfect for what Tcherniakov wanted from this character though I would have preferred more lyricism. The standout performance in this Der Freischütz was Kyle Ketelsen as Kaspar/Samiel who was ingratiating when enticing Max to join him for a drink, sounded darker with a hint of menace when planning their Wolf’s Glen rendezvous, and intoned with cavernous spectral malevolence as Samiel. Anna Prohaska was an unusually strong-willed and firmly voiced Ännchen whose interest in Agathe is rather more than simply platonic. It comes as a surprise that this Ännchen would ever be so playful as to indulge in the famous aria about a ghostly dog she sings in the third act!

Golda Schultz does not act Agathe with the conviction of her colleagues though I did recognise how conflicted she was in her duty to her father, passion for Max, and (hidden?) feelings for Ännchen. Nevertheless, her major arias, ‘Wie nahte mir der Schlummer … Leise, leise’ and ‘Und ob die Wolke sie verhülle’ would be showstoppers had there actually been anything to stop this audience- and interval-less performance. Both were prayerful, rapturous when necessary, beautifully and eloquently sung to showcase Schultz’s rich vocal palette. All the secondary roles were resoundingly well-sung and notably well-characterised and included two magnificently resonant bass voices in Bálint Szabó as the cigar smoking big shot Kuno and Tareq Nazmi as the conciliatory deus ex machina Hermit.

Jim Pritchard

To watch this Der Freischütz click here.