United Kingdom Sibelius, Elgar, Beethoven: Sheku Kanneh-Mason (cello), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla (conductor). Symphony Hall, Birmingham, performance (10.11.2020), livestreamed from the CBSO website on 19.11.2020. (JQ)

United Kingdom Sibelius, Elgar, Beethoven: Sheku Kanneh-Mason (cello), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra / Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla (conductor). Symphony Hall, Birmingham, performance (10.11.2020), livestreamed from the CBSO website on 19.11.2020. (JQ)

Sibelius – Lemminkäinen’s Return

Elgar – Cello Concerto in E minor

Sibelius – The Swan of Tuonela

Beethoven – Leonore Overture No.3

All orchestras have been badly hit by the enforced Covid-related shutdown of most concert activities since March 2020. However, there is a case to be made that some of the keenest misfortune has befallen the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra because the suspension of most concert activities came just at the time when, over the 2019/20 and 2020/21 seasons they were celebrating their centenary. Plans were thrown into disarray and two commemorative dates that came under particular threat were the concerts scheduled for 5 September and 10 November 2020.

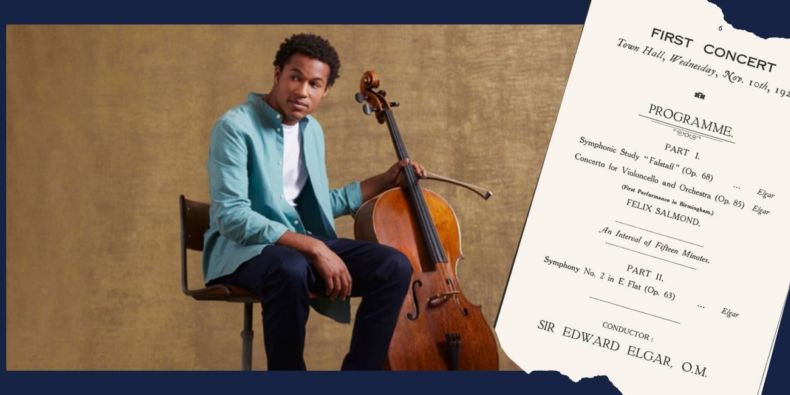

The first of those two dates, 5 September, is an especially significant date in the orchestra’s history because it was on that day in 1920 that what was then the City of Birmingham Orchestra gave its very first concert. Undaunted by Covid restrictions, the CBSO used considerable ingenuity to put on a fine concert on the day in question (review). On that occasion, the orchestra’s Osborn Music Director, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla could not take her place on the podium because she was still on maternity leave. Fittingly, Sir Simon Rattle, a key figure in the orchestra’s history, did the honours instead. This concert marked another auspicious occasion: the CBO’s first symphony concert. On that evening, 10 November 1920, the orchestra engaged Britain’s foremost composer, Sir Edward Elgar to conduct a programme of his own music. As Richard Bratby has pointed out in his splendid centenary history of the CBSO, the concert in question was a brave proposition. Elgar conducted his Symphonic Study, Falstaff, the Cello Concerto and the Second Symphony. One hundred years on, we look at that programme and see three masterpieces. However, both Falstaff and the symphony had been coolly received when they were unveiled before World War I and in 1920 the public was a long way from taking either work to their hearts. As for the Cello Concerto, it was only about a year since the work’s premiere and its austere, autumnal character, far removed from the flamboyance of the Violin Concerto, was yet to be widely appreciated. Richard Bratby relates that the programme probably deterred some Birmingham music lovers; the hall was far from full. At least, though, the CBO had an audience.

I strongly suspect that in the pre-Covid days, the CBSO planned a large-scale celebratory concert for 10 November 2020, quite possibly involving their excellent choruses. In the end, the UK’s latest lockdown meant that although the orchestra was able to play this short but not insubstantial programme in its home auditorium, Symphony Hall, it was obliged to do so without any audience present. I had planned to go to review the concert but, like everyone else, I had to settle for watching the concert via the orchestra’s website. Appropriately, the concert was recorded on 10 November.

The programme was shrewdly selected. Not only did it show off the orchestra, but also there was significance behind the choice of each work. The Elgar concerto was repeated from 100 years ago and for this performance the CBSO welcomed back a favourite soloist, Sheku Kanneh-Mason, who also played in their September Centenary concert. The two Sibelius pieces acknowledged the fact that the Finnish master conducted a programme of his own music in the orchestra’s inaugural season; that was in February 1921 when the Third Symphony was among the works performed. The two items from the Lemminkäinen Legends were not heard on that occasion but I wonder if their inclusion was deliberately chosen by Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla to recall another, more recent occasion. In January 2016 she conducted the CBSO in a splendid concert which included all four of the Legends (review). That concert, many felt, was, in effect, her final audition with the CBSO: her appointment as Music Director was announced not long afterwards. The final item on the programme was undoubtedly an acknowledgement of Beethoven 250.

The demands of social distancing meant that the CBSO was obliged to muster a string section that was less substantial than usual – only four desks each of first and second violins, with the rest of the string choir in proportion. However, at no time did I feel that the orchestral sound lacked body.

Lemminkäinen’s Return is early Sibelius and is an excellent example of his nationalist vein. The piece made an ideal opener to this programme. Ms Gražinytė-Tyla directed a taut, urgent performance that was full of driving energy. The incisiveness of the CBSO’s playing was admirable. We heard The Swan of Tuonela after the Elgar concerto. This highly evocative piece shows Sibelius in a very different vein. The spare orchestral textures were very well realised in this performance and though much of the music is subdued in tone – certainly by comparison with Lemminkäinen’s Return – the piece is nonetheless dramatic, albeit in a very different way. In this connection, the dark processional near the end, where unison strings play against an ominous background of timpani and low brass, was especially effective. In a fine performance attention was rightly claimed by Rachel Pankhurst’s plaintive cor anglais solos. However, my ear was also caught by the poignantly poetic cello solos played by Eduardo Vassallo. My only reservation was that in this work – but not in the others – I was conscious of the orchestra sounding too close. This was the one occasion when I longed to hear the orchestra at something more of a distance in the natural acoustic of Symphony Hall.

Sheku Kanneh-Mason has developed a strong rapport with this conductor and orchestra, I mentioned that he took part in the recent Centenary concert but the connection goes back further; for example, Ms Gražinytė-Tyla and the CBSO partnered him in his debut concerto recording, which was very positively received by my colleague Steve Arloff. Since then Kanneh-Mason’s stock has risen still higher and, among other things, he has set down a recording of the Elgar concerto, though on that occasion he was joined by the LSO and Sir Simon Rattle. I have heard that disc only once but I must admit I rather agreed with the view of Michael Wilkinson who, while finding much to admire was not as moved by Kanneh-Mason’s performance as by those of other notable past interpreters. I was keen, therefore, to experience this fine young cellist in the work again and I must say straightaway that his performance made an excellent impression.

In the first movement, Kanneh-Mason’s lovely tone enabled him to do full justice to the music’s autumnal lyricism. The performance was well paced; there was, for example, a pleasing lilt to the second subject. The soloist’s virtuosity is tested by the brief, scampering second movement and the test was fully passed here. I also admired the alert support from the CBSO. The slow movement, though short, says an awful lot in a brief span of time. Sheku Kanneh-Mason was fully alive to the poetry in the music, once again his tonal quality was a great asset. He articulated the music with just the right degree of feeling, not overdoing the emotion. I liked the tranquil manner of Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla’s conducting. Both soloist and orchestra gave a spirited account of the main body of the finale. The most memorable passage in this movement comes when Elgar revisits the mood and material of the slow movement. Here, the challenge for soloist and conductor is to convey the right intensity of feeling while not losing the shape of the music; that challenge was successfully met. In normal circumstances I am certain that this fine performance of the Cello Concerto would have received an ovation, but the absence of an audience precluded that.

Just as Lemminkäinen’s Return was an excellent curtain-raiser, so the choice of the third Leonore overture was a fine way to conclude this hour-long concert. What a fantastic piece it is! Of course, Beethoven was right to call the work an overture but it’s almost a short tone poem in which the major themes – and events – of Fidelio are reviewed. In fact, in a verbal introduction to the piece Ms. Gražinytė-Tyla aptly described it as ‘an opera in fourteen minutes’. I thought her conception of the piece was an excellent, dramatic one. She and the players invested the slow introduction with plenty of tension. The main Allegro was thrusting and positive yet, sensibly, not rushed. Later on, the distant trumpet calls from the off-stage recesses of Symphony Hall were expertly managed. The overture ended in a blaze of optimism and celebration. Let’s hope that proves to be a metaphor for the performing arts in these present dark days.

We have to have confidence that organisations like the CBSO will come out of the current emergency and will thrive once again in front of full houses and playing the complete range of their repertoire, including the large-scale set-piece works to which Symphony Hall is so well suited. One could wish that the orchestra had been able to celebrate their centenary in the way that I’m sure they originally planned. But, actually, the fact that the orchestra has now twice celebrated its centenary, triumphing over Covid restrictions, and has also put on a range of small-scale events in recent weeks, offers the best possible testimony to the CBSO’s resilience. Beethoven’s musical vision of a world in which Good triumphs was an uplifting way for the orchestra to launch its second century.

I listened to the concert when it was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 17 November in order to hear the orchestra’s sound to best advantage. Heard on the radio, the CBSO sounded in fine fettle. I subsequently watched the concert online and enjoyed seeing the orchestra and their dynamic Music Director in action again. The online relay uses the BBC sound, and the concert was filmed by River Rea Films. I thought the camera work was very good. Only one aspect troubled me. Wisely, the auditorium itself was in darkness so that we were not conscious of the rows of empty seats. The stage was only lit in a dim blue light, however. I found that this meant the players were unduly hard to see; I think it would have been preferable to have lit the platform a little more brightly. This video on demand is available to view from Thursday 19 November until Friday 18 December 2020. Click here for more information.

The CBSO will be streaming two further concerts in the coming weeks. You can find details here.

John Quinn